Two final huts (except they are cabins) 9 April 2011

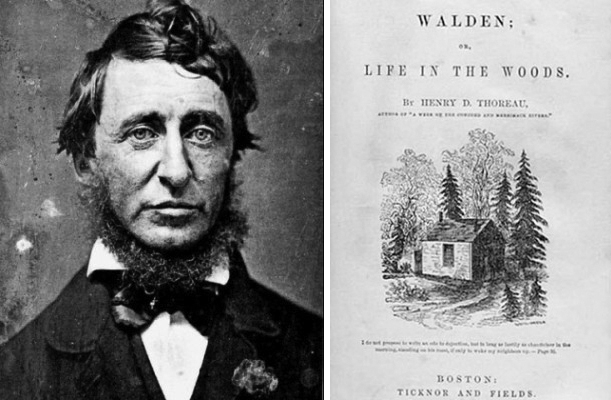

In 1852 the rustic cabin achieves immortality as a place to escape from one’s everyday life when Henry David Thoreau publishes an account of his self-imposed, semi-seclusion on the shore of Walden Pond from 1845 to 1847.

There he lived, mostly self-sufficient, having removed himself from “civilized life” to a house he built for himself for the economical sum of $28.12½ . His cabin was as much as a philosophical space as a physical one, as Thoreau freely admits. It is not enough to get away; to truly “live deliberately,” it matters how one does it. So, with a borrowed axe, Thoreau cleared a site and hews the timber to frame his new home. To roof and enclose the cabin, Thoreau purchased an Irishman’s shanty—he is untroubled that the Irishman and his family are still in residence—which he disassembles for its boards and shingles. His use of these recycled materials was intended to shock the reader, as much as his observation that the log huts of the poor are the most interesting dwellings in the country. With Victorian materialism coming into full flower, Thoreau was deliberately snubbing the nation’s cultural and architectural tastemakers by proclaiming the “unpretending” humble abode the most worthy of admiration and emulation.

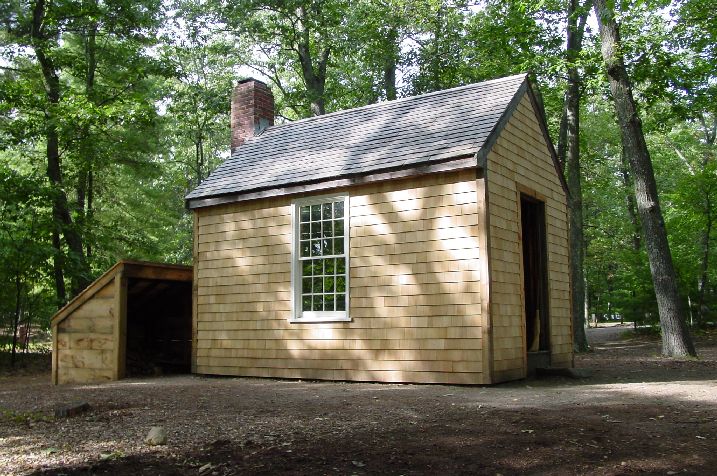

Escaping to his cabin at Walden, Thoreau avoided, if only for a short while, those “lives of quiet desperation” to which we are fated. Alas, the same cannot be said of visitors to Thoreau’s (replica) cabin today: the parking lot is crowded and gift shop is full of tchotckes (I bought two bumper stickers).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Still, peering into the cabin you can sense how Thoreau intended to confront just life’s essentials, stripping away material excess to work simply, play simply, dress simply, and eat simply. This was the only life he believed he could possibly lead within the honest walls of his honest cabin. That the prophet of self-reliance had his mother do his laundry was kept a secret for many years.

Around 1972, a different sort of philosopher built a rustic cabin for himself in the wilds of Montana. Theodore Kaczynski’s cabin is similar to Thoreau’s. It is small and simple, a single 10’ x 12’ room with a pitched roof; it is hand made of rough materials, plywood and tin; it has no electricity or running water. Like Thoreau, Kaczynski removed himself to the cabin to escape the pressures of civilization and begin what becomes his life’s work, writing a 35,000 word manifesto excoriating late industrial society and building letter and package bombs that, over the course of two decades, will kill three people and maim two dozen more.

When the FBI arrested Kaczynski as the Unabomber in 1996 (fifteen years ago this month), his remote dwelling was subjected to the harsh glare of the media spotlight. The rustic cabin’s most obvious virtues now became its most notorious vices: physical isolation is deviant; intellectual solitude is psychotic; living without modern conveniences is abnormal. In 1997 the cabin was loaded onto a flatbed and trucked to California where it was featured prominently in the Unabomber’s trial. Far more totemic than O.J.’s glove, the cabin in the courtroom was less a piece of evidence than a star witness bearing mute testimony to the hopes and fears of an entire culture—rugged individualism gone terribly awry.

When the trial ended in 1998 the cabin was sent to a storage facility in Rancho Cordova, California where it was, in effect, incarcerated, as Richard Barnes observed when he documented the cabin a series of haunting photographs. Barnes explained his pictures of the cabin as an attempt to “bridge the gap between the banal and the extraordinary, the cult of celebrity and the seductiveness of the infamous.”

The same can be said of Constantin and Laurene Boym’s Unabomber Cabin, a 2.5” high cast nickel miniature that debuted in 1998 as part of the desingers’ Buildings of Disaster series. A partially ironic commentary on media saturation, a partially serious commentary on the need to mark and memorialize, the souvenir Unabomber Cabin was available for purchase at better design boutiques for several years. Until recently, it was also available at the online store of Boym Partners. Sometime around the turn of the century, the first agent to enter the cabin during the 1996 FBI raid purchased the miniature cabin as a way of making peace with his connection to it.

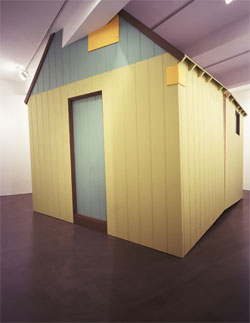

The cabin would continue to inspire artists for a number of years. In 2004 Daniel Joseph Martinez debuted “The House America Built,” a full-scale reproduction of the cabin done up in bright colors from Martha Stewart’s Signature line of Sherwin-Williams paints. In 2008, the After Nature exhibition at the New Museum of Contemporary Art featured Robert Kusmirowski’s “Unacabine,” also a full-scale version of the cabin, but this time an exact replica–no designer colors, just faux stains and weathering. I remember seeing After Nature, but had no recollection of Kusmirowski’s piece, probably because Maurizio Cattelan’s life-size headless horse made a bigger impression (i.e. freaked me out more). Thankfully, David Smiley reminded me about the “Unacabine” a few weeks ago.

The cabin also continued to make news. In 2003, title was transferred to Scharlette Holdman, a member of Kaczynski’s defense team, but for reasons that are unclear she did not take possession of it. Around the same time, the cabin was offered to the Smithsonian; the Institution declines, citing the cabin’s size as a significant reason it did not pursue acquisition. This tests credulity: the cabin is much smaller than many objects in the collection of “American’s attic”: the Apollo 11 capsule, the 1401 steam locomotive, the ENIAC Accumulator #2, the Hart House from Ipswich. At any rate, shortly thereafter, the cabin was to be demolished but for reasons that are unclear it was spared and placed in safe storage at SafeStore near Sacramento.

In 2008, it appeared at the Newseum in Washington, DC–decidedly not the Smithsonian, but just a few blocks up Pennsylvania Avenue from FBI Headquarters. Part of a show called “G-Men and Journalists,” the cabin was displayed because, according to one museum official, it was a “definite media hook.” At the very least, it attracted the attention of the Unabomber himself, who protested its display in the museum.

In 2010, John Pistelak Realty of Lincoln, Montana offered the land on which the cabin sat for sale for $69,500, advertising it as a chance to purchase “an infamous piece of U.S. history.” In a striking bit of understatement, the land was described in the listing as “very secluded.” It is not clear if there were any bidders.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.