“There were many of the modern American houses here.” 22 July 2011

When Thoreau wrote those words in his book on Cape Cod (published posthumously in 1865), he didn’t mean it as a compliment. He had nothing but disdain for the “modern” houses he saw on the Cape, white painted boxes built of “dimension timber, imported from Maine.” (The italics are his.) Not surprisingly, given the romantic rusticity he displayed in Walden, Thoreau preferred the Cape’s “old fashioned and unpainted houses,” which seemed to him “more comfortable, as well as picturesque.” But if Henry David had returned to the Cape a century later he might have found modern American houses that were more to his liking.

I certainly did when I stopped off in Wellfleet in June to participate in a summer program of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust. In addition to giving a talk on the modern vernacular, I was invited to spend a few days in Charlie Zehnder’s Kugel-Gips House (1970), recently restored by the CCMHT and available to the public as a rental property that provides this small non-profit with vital income to support its programs. Working with the National Park Service, and under the energetic leadership of Peter McMahon, the CCMHT is rescuing, preserving, and studying modernist architecture on the Cape—a legacy that deserves to be much better known.

It stretches back to the 1940s, when Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Serge Chermayeff, and other recent European émigrés began to make summertime visits to the Outer Cape. In Wellfleet and Truro, in particular, these modernist luminaries mixed with local, self-taught designer/builders like Jack Hall and Jack Phillips.

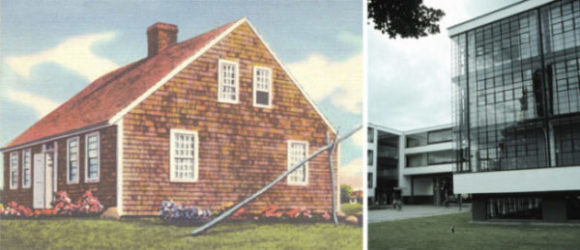

Early on, the two Jacks saw parallels between the New England vernacular and the new architecture in Europe, and they started making buildings—cottages and small commercial structures—that fused the two, combining the handcrafted materiality and modesty of a Salt Box with the structural openness and lightness of the Bauhaus.

Early on, the two Jacks saw parallels between the New England vernacular and the new architecture in Europe, and they started making buildings—cottages and small commercial structures—that fused the two, combining the handcrafted materiality and modesty of a Salt Box with the structural openness and lightness of the Bauhaus.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the cottage that Jack Hall designed and built in 1960 for Ruth and Robert Hatch, a painter and Nation editor, respectively. From afar, the cottage appears essentially of the place, a perfect embodiment of a seaside landscape, its battered boards and weathered frame as bleached and stained as a fishing pier. Up close, the cottage displays a modernist sort of formal rigor—well, as much rigor of form as a stick-built dwelling perched on pilings in the dunes can have. But that’s actually a good thing: the Farnsworth House it ain’t, nor does it pretend to be; it’s too intuitive for that.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Still, standing on the Hatch decks looking out into the dunes, one can’t help but think of Mies’ project for the Resor House and the way its structure consciously framed the landscape of the Tetons. And the cottage has other modernist affinities, too, with buildings as diverse as the Gropius house in Lincoln, Mass (especially the screened in porch) and, on the opposite coast, the Eames house in Pacific Palisades (in its potential for flexibility).

Here in Wellfleet, Hall designed a straightforward rectangular grid of wood, seven by five bays, and used it to define the cottage’s structure and its space. Each cube, or sequence of cubes, serves a particular programmatic need: terrace, living room, kitchen, bath, bedroom, studio, etc.

Open air corridors, also defined by the cubes, provide access to most of these spaces, their entrance doors shielded by the slight cantilever of three hovering roof planes whose presence is especially visible from the top of the surrounding dunes.

Open air corridors, also defined by the cubes, provide access to most of these spaces, their entrance doors shielded by the slight cantilever of three hovering roof planes whose presence is especially visible from the top of the surrounding dunes.

A series of moveable panels, operated by a rope-and-pulley system, do double duty as storm shutters and shading devices. Taken together, the frames, panels, and roofs give the cottage a kind of shaggy modularity.

The Hatch Cottage is the next house the CCMHT will restore, after it completes detailed documentation this summer. And the reason it needs to be restored is part of the complicated back-story of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

As the art and design circles of the Outer Cape intersected and widened during the mid-century decades, an astonishing number of inventive modern buildings were erected throughout the area, in the woods, on the ponds, above the dunes, and overlooking the bay and the ocean. This continued even after the National Seashore boundary was fixed in 1959, which meant that those post-1959 houses would eventually become the property of the federal government. Thus, the 1960 Hatch Cottage became Park Service property after Ruth Hatch died in 2004. Originally, the National Park Service intended to demolish these houses in order to “restore” the seashore to a more “natural” state (or as natural as a place can be when it’s been occupied by humans for thousands of years).

The history does not record whether anyone noticed that the NPS was proposing to tear down modern buildings on the Outer Cape at the same moment it was erecting modern buildings on the Outer Cape as part of its Mission 66 program.

Designed by Ben Biderman of the NPS Eastern Office of Design and Construction, the Salt Pond Visitor Center of 1964 is more conservative than many of its western contemporaries (those at Capitol Reef and Mesa Verde, for example), with its nearly symmetrical plan and ponderous, hexagonal central pavilion. The roof is a cross between Richard Burke’s Pizza Hut prototype (also of 1964) and a run-of-the-mill Howard Johnson’s from that same period, and it is tempting to push this parallel further given HoJo’s long history on the Cape, the chain’s second unit having opened in nearby Orleans in 1932.

Designed by Ben Biderman of the NPS Eastern Office of Design and Construction, the Salt Pond Visitor Center of 1964 is more conservative than many of its western contemporaries (those at Capitol Reef and Mesa Verde, for example), with its nearly symmetrical plan and ponderous, hexagonal central pavilion. The roof is a cross between Richard Burke’s Pizza Hut prototype (also of 1964) and a run-of-the-mill Howard Johnson’s from that same period, and it is tempting to push this parallel further given HoJo’s long history on the Cape, the chain’s second unit having opened in nearby Orleans in 1932.

The Visitor Center’s flanking wings are far more satisfying than the central pavilion: with their asymmetrical rooflines and contrasting shake and brick cladding they are simultaneously of the Cape and the modern era. Out there, in a place that Thoreau thought was “as wild and solitary as the Western Prairies” genius loci met the zeitgeist. And that’s what the Cape Cod Modern House Trust is working so hard to preserve.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.