A Post-Script on Blueberries in Winter 23 December 2009 No Comments

It may seem odd to still be writing about Maine nearly four months after my return from Vactionland, but the Pine Tree State has a way of staying with you. While this is due mostly to the essential quality of the place (see Genius Loci in Acadia), the quantity of made in Maine products that accompanied my return home must also be taken into account. Some years, it’s potatoes. They’re the state’s largest crop and the varieties that come down from Aroostook County are astonishing. But this year, perhaps because I’d been to Idaho in the spring, and had even stopped off at the Idaho Potato Museum in the town of Blackfoot, the spuds of Maine spud held no allure.

Thus, this year, it was blueberries, the wild, low-bush variety that grow on 60,000 Down East acres. According to the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, Maine is the largest producer of wild blueberries in the world, which explains why they turn up almost as often as lobsters on tourist tchotckes.

Though vanccinium angustifolium are charmingly picturesque, I prefer mine to be comestible rather than graphic. They taste best when warmed by the sun on a granite topped mountain in Acadia, where the act of picking them after a vigorous hike on a rusticator’s trail is shamefully enjoyable—a little agricultural labor for the bourgeois-at leisure Slow Food set, sort of like Marie Antoinette in the Hameau at Versailles.

By the time I’ve picked enough for a couple of pies, stooping over and crouching down have lost their appeal, and no small order of rest is required.

But the desire for wild blueberries remains as acute as the pain in my lower back and it becomes only stronger once the car is pointed south. So this year I decided to return with a complete inventory. Blueberry Ale from the Atlantic Brewing Company in Bar Harbor is much like a traditional lambic.

Back River blueberry gin from the Sweetgrass Distillery in Union makes an excellent martini if you prefer strong botanicals, as I do. The blueberries are a fine compliment to the juniper.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

These blueberry beverages are immensely satisfying, but I feared they were too far removed from the thing itself. So this year I also returned home with ten pounds of fresh blueberries purchased from an elderly couple running a farm stand out of their garage somewhere on U.S. 1 south of Ellsworth.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

My friend Charles, who lives in Portland and can be accurately described as the King of Pancakes, had assured me that you can stick a box of blues in the freezer and scoop them out as needed, all winter long. I believed him, but I had to weigh my desire for blueberries against pragmatics. When you don’t have the luxury of a single-family-detached-house-sized kitchen, a 10-pound box of blueberries requires a serious piece of freezer real estate.

…..

It would mean displacing 4 pounds of vegetarian suet and 6 pounds of Smith College pecans, not to mention a couple of bottles of vodka. Were the contents of that 14 x 10 x 4 box going to be worth the space?

Yes. On a cold morning in December at the start of winter, a warm muffin filled with wild Maine blueberries is a very good thing.

Still, this commitment to blueberries was not without consequences. A subsequent purchase of fifty pounds of grass-fed, pastured beef from some friends in Duchess County necessitated off-site storage in a basement freezer in el Barrio.

I’m still searching for a recipe for beef and blueberry stew. Suggestions welcome.

Genius Loci in Acadia 29 August 2009 No Comments

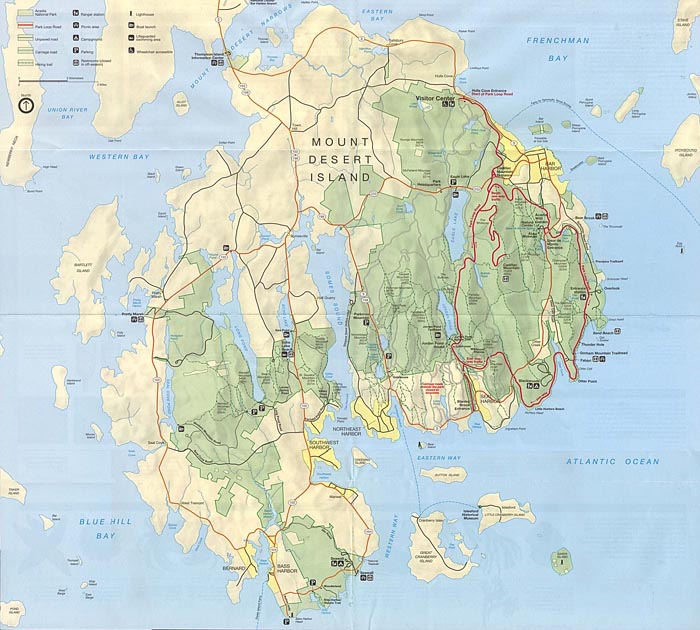

On an island off the coast of the North American mainland, near the narrows of Somes Sound, across from Norembega Mountain, between Fernald Point and Clark Point, a few steps from the Atlantic, in Southwest Harbor, Maine (at 44.278º North and 68.311º West, to be precise), one is easily, happily, and phenomenologically seduced by the spirit of the place.

The sight of the mountains and forests, the smell of evergreen and seaweed, the feel of the shells and the rocks, the taste and the sound of the ocean. These are why summer people come to the Maine coast, and certainly why they’ve been coming to Mount Desert Island since the first rusticators arrived in the decades after the Civil War.

By train, steamer, and ferry from Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, they arrived eager to consume the same landscape that Thomas Cole and Frederic Church captured in their oils and watercolors. Beginning with their village improvement societies and ending with their successful effort to create the first national park east of the Mississippi, the rusticators shaped Mount Desert Island as surely as nature and geography.

The earliest white settlers on the island, who arrived mainly after 1759 when the English drove the French out of Acadia, lived with and from the land and the water. They were the first to harvest the island’s natural resources and to make Maine “Maine.”

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

But it was the rusticators who understood how to exploit the genius loci for their pleasure, profit, and eventually for the public good, as is still evident in what they built across the island–mountain trails and town paths, scenic drives and carriage roads, inns and resorts, piers and houses. These were built for the seasonal tourists, but they became the essence of the place.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

The cottage I’m renting in Southwest Harbor is called “the Legacy” because it’s been passed down a generation or two since it was built in the 1940s, but it could just as easily refer to the Acadia passed down by the Eliots and the Rockefellers.

Though the pitch of the roof and the knowing placement of the picture windows nod to mid-century architectural taste (the next house down the coast, by contrast, is an over-scaled Dutch Colonial from the 20s), the granite fireplace, pine-framed rooms, and cedar shake exterior evoke the rustic rusticity of the rusticator’s image of Down East Maine.

But placeness here, as everywhere, means more than building materials and manicured wilderness; it also involves food culture and traditions. The rusticators, like their island hosts and the native Wabanaki before them, were locavores avant la lettre. Fresh haddock, cod, oysters, clams, mussels, and, of course, lobsters.

Though dining in the rough was more a necessity than a choice in the 19th century, it has considerable appeal even in the 21st, at least where lobster is concerned since the whole point of eating at a pound is that, at least in theory, you are guaranteed the freshest bottom feeders possible.

Even if the pound functions as a dealer/middleman, there’s the added value of the picturesque–the harbor, fishing boats, stacked pots and buoys, picnic tables, gulls, mosquitoes, Teva sandals, Life is Good t-shirts, etc.

This year I bought steamers and cherry stones from a guy called Rat who was selling them out of an old refrigerator in a cluttered garage next to a mildly ramshackle house in Bar Harbor. I was attracted by his sign, especially his use of “safe shellfish” as a descriptor.

While it is true that many areas on the island are closed to digging because of paralytic shellfish poisoning, the need to advertise bivalve safety is both amusing and depressing, sort of like service stations advertising “clean restrooms.”

For the record, I ate two dozen of Rat’s clams for dinner with no ill effects though steaming them in an entire bottle of vernacchia di San Gimignano might have killed whatever toxins lingered in those mollusk filters.

Rat told me that he used to sell his clams to Pectic Seafood before it moved off the island. I knew Pectic. It was in a little trailer of a building right next to the house where its owners lived, up a quarry road well off the main highway in Mt. Desert. When the sons took over the business they closed this location and opened a big store close to the Wal-Mart sprawl of Route 3 in Ellsworth.

While the economics of year-round traffic probably drove this decision, Rat and I both understood that something had been lost in the relocation. He declared the original Pectic a real “mom-and-pop operation,” the sort of place that appealed to the summer people he described as “those folks in Northeast Harbor with their Philadelphia accents.” His place, by his own admission, was a little too rough for their tastes, but not for mine apparently, though I wasn’t sure if it was the New York plates on my car or my lack of a Main Line lockjaw that met with Rat’s approval.

When I told Rat that I liked his sign on Route 102 he laughed that I was about the only person who did. The Japanese tourists told him he needed neon; the village improvement types told him he needed nicer lettering. The authenticity of place is in the eye of the beholder.

Next: genius loci accinium angustifolium; or, where the wild blueberries grow

In the Wake of the Half Moon 31 July 2009 No Comments

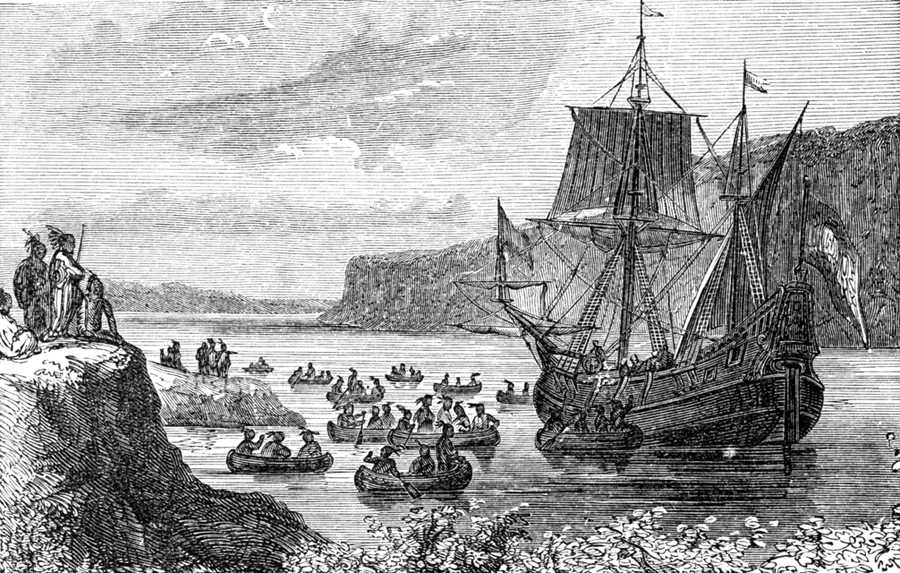

In the summer of 1609 Henry Hudson and a crew of twenty Dutch and English sailors entered what is now New York Bay and sailed their sloop, the Half Moon, up the wide river that today bears the explorer’s name. Four hundred years later, I jumped in the river after them.

Hudson was looking for an uncharted passage to China. I was looking for a buoy-marked passage to 79th Street. He had to keep an eye out for potentially dangerous natives. I had to keep an eye out for potentially dangerous flotsam. Several of Hudson’s men were assaulted by the Algonquin. I didn’t encounter so much as a discarded condom. It took Hudson all day to sail from the bay to the tip of the island. It took me twenty-five minutes to swim from Cherry Walk to the Boat Basin.

History has not recorded what Hudson was thinking as he passed the island’s western shore. I was thinking about its transformation from deciduous forest to concrete jungle, from sandy beaches and salt marshes to sea walls, highways, monuments and towers. Well, that and how to avoid getting kicked in the face by the swimmer in front of me.

Still, one’s perspective of the city changes from the water. Only on the water do you get a sense of the true extent of New York’s aquatic self, 578 miles of coastline slung out over three large islands and a spit of the North American mainland. Only in the water do you get a sense of the true extent of New York’s post-industrial self, a vast recreational waterscape in place of what was once a hardworking waterfront.

Moving swiftly through the current, surrounded by kayaks and pleasure craft, you realize how thoroughly the city of homo faber has become the city of homo ludens. And this might explain why there were nearly 4,000 other people in the water on the day I did in the New York City Triathlon.

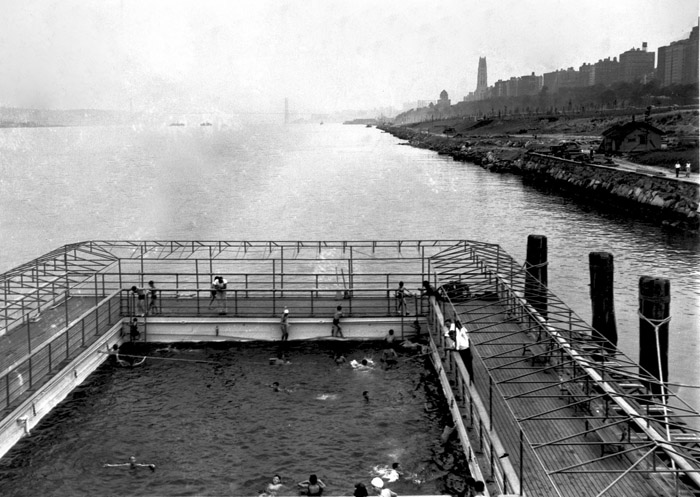

Until the middle of the 20th century, swimming in the NYC-stretch of the Hudson was a normal summer activity. While the city lacked the lifeguard beaches found in the Palisades on the New Jersey side of the river, from the 1870s to the 1940s it had a series of floating baths that moved around on pontoons to the apparent delight of swimmers up and down the west side of Manhattan.

A perfect example of nature tamed, the baths were filled with the half-salt/half-fresh water of the river itself while protecting swimmers from the river’s considerable tides, currents, and depths. The last of the floating baths were moored at West 96th Street, near where I started my swim. The triathlon’s temporary pier, with its steel decking and banners, seemed like a fitting, if less paternalistic, heir.

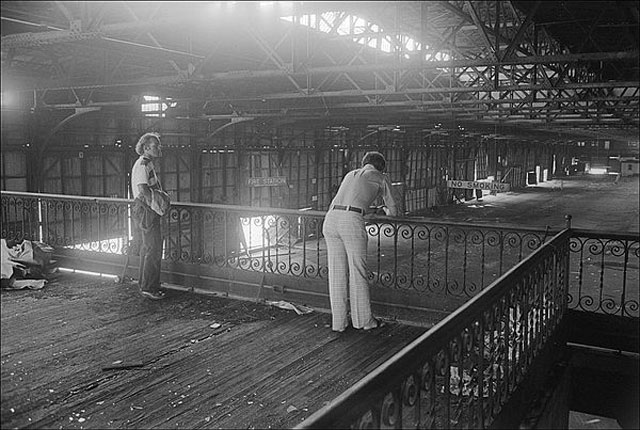

When the floating baths were finally decommissioned at the start of WWII, the water quality of the Hudson was seriously degraded by sewage and industrial waste, most notoriously PCBs, and this pollution continued until long after the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972. By then the Hudson’s heyday as a working waterfront was long over and the city settled into a gloomy state of fluvial disregard.

This isn’t really surprising: between the highway and the rotting piers was an urban no man’s land that had appeal only for those reveling in the sweet moment of liberation between Stonewall and AIDS (and joyously documented in Gay Sex in the 70s).

Even Riverside Park had seen better days. Though Robert Moses rebuilt this “wasteland” in the 1930s, covering the New York Central tracks to give pedestrians, and of course automobiles, access to the waterfront, by the 1970s the esplanade was so decrepit and crime-ridden that when Riverside Park turned up as the setting for a climactic gang battle between the Baseball Furies and the Warriors, Walter Hill’s 1979 cult classic starts to seem like cinema verité.

Thirty years later, there’s a café where the Warriors bested their enemies. It’s only open until 11 pm but most nights in the summer the crowd lingers until much later, finishing their beers and hanging out with their dogs.

It’s the same up and down the waterfront, which is now part of a city-wide greenway. The rebuilt piers have lounge chairs and wifi; the industrial detritus is landmarked and turned into art; the esplanade is planted with the same species of trees and grasses that Henry Hudson would have seen back in 1609.

Past is somehow prologue walking the river in 2009: the Machine Age Manhatta of Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler’s film meets the primeval Mannahatta of Eric Sanderson’s digital reconstruction. And the Hudson River is cleaner than it’s been in a century; so come on in, the water’s fine.

Up to Speed, On the Road, By the Numbers 1 July 2009 No Comments

I returned to New York at the end of May, 75 days and nearly 18,000 miles after I left in March. That was 37 days and 1300 miles ago. I had every intention of writing a brilliant conclusion for the Great American Road Trip, but la vie quotidienne got in the way–deadlines, engagements, distractions, enthusiasms. Or maybe everyday life didn’t get in the way as much as it merged seamlessly with the road trip, like the Clubman pulling into an interstate egress lane without decelerating.

Loyal readers will, I hope, forgive that minor poetic lapse, but to prevent any further metaphorical indulgence I am moved to give Kerouac the (nearly) final word:

“So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old brokendown river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable bulge over to the West Coast, all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the evening-star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all rivers, cups the peaks in the west and folds the last and final shore in, and nobody, just nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Neal Cassady, I even think of Old Neal Cassady the father we never found, I think of Neal Cassady, I think of Neal Cassady.”

Substitute the fourteenth floor of a pre-war high-rise for Jack’s brokendown river pier and a dozen close companions for his singular Neal Cassady, and you know how I feel right now, looking out the window at New Jersey.

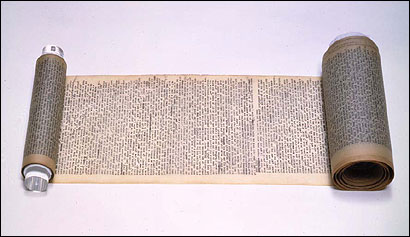

Kerouac typed the first draft of On the Road on eight long pieces of trace, taped together to form a scroll.

I typed the first draft of my on the road on a six year old pc, the touch screen of an iPhone, and the non-mechanical shutter of a digital camera. What I’ve got is not as materially satisfying as 119 feet of trace, but 12 GB of zeros and ones at least possess some small measure of virtual heft.

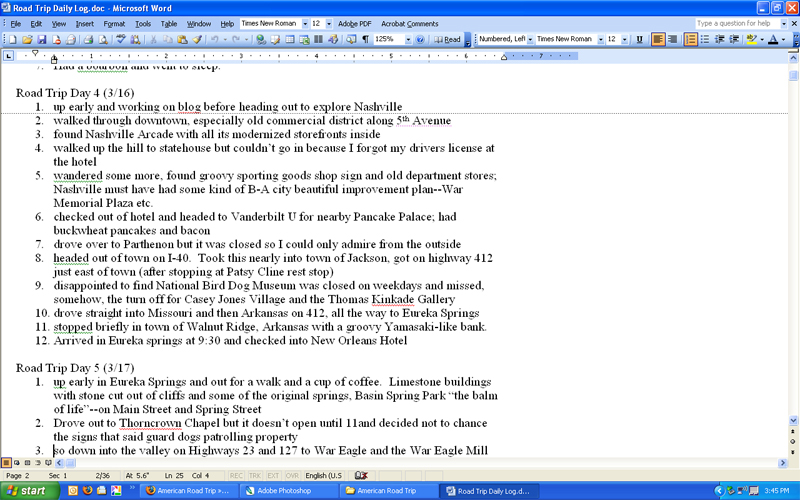

Taken together and sorted categorically (but arranged here numerically), all those bytes yield the following information (thorough if not exhaustive):

17,794 miles; 8,639 photos; 500 gallons of gas; 131 postcards; 75 days; 36 oysters; 35 buffaloes; 33 royal medjool dates; 30 states; 29 plays of Rufus Wainwright singing “King of the Road”; 28 friends; 28 museums; 23 modernized storefronts; 21 Vignelli NPS brochures; 20 hotels;

14 pieces of pie; 13 national parks; 11 airports; 10 state capitals; 9 Saarinen buildings; 9 historic houses; 8 burgers; 7 traffic jams; 7 sequined jumpsuits; 6 national monuments; 6 times across the Continental Divide; 6 Sullivan buildings; 6 college campuses; 5 barbeque meals;

5 shopping malls; 4 snow storms; 4 nights camping; 4 martinis; 4 t-shirts; 4 colossal statues; 3 national memorials; 3 monuments of land art; 3 cell towers disguised as local flora; 2 Morphosis buildings; 2 Herzog & deMeuron buildings; 2 missions; 2 speeding tickets; 2 car washes;

5 shopping malls; 4 snow storms; 4 nights camping; 4 martinis; 4 t-shirts; 4 colossal statues; 3 national memorials; 3 monuments of land art; 3 cell towers disguised as local flora; 2 Morphosis buildings; 2 Herzog & deMeuron buildings; 2 missions; 2 speeding tickets; 2 car washes;

2 bottles of whiskey; 2 bears; 2 dairies; 2 ancient earthworks; 2 trips to Las Vegas; 2 scholarly archives; 1 TV show taping; 1 drive across the Hoover Dam; 1 Big Boy; 1 oil change; 1 national preserve; 1 national heritage area; 1 national grassland; 1 national historic site; 1 tiki bar; 1 hot springs; 1 moose; 1 tipi, 1 John Deere belt buckle.

What is not accounted for here will undoubtedly turn up later as I continue to contemplate the American culture I found in the buildings and landscapes and people and food I discovered on the road. Of course, as Soviet writers Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov put it after they concluded a two-month coast-to-coast drive in 1935: “The fact that you discovered America means nothing. The important thing is that America discovers you.”

Fitness and Civilization 22 May 2009 No Comments

Power walking, it turns out, is one of the hallmarks of the American civilization. I had seen plenty of it in Los Angeles: folks in groups of two and three, arms swinging with their strides while making their way slowly but determinedly through the hills of Griffith Park. I hadn’t paid much attention to these people maybe because I was too busy gasping for breath while attempting to run through the hills of Griffith Park, or maybe because their approach to urban fitness was so familiar as to be unremarkable.

Once I left the coast, the power walkers gave way to hikers, rock climbers, and mountain bikers, at least from my admittedly narrow vantage point. In Moab, in southern Utah, the wildness of the geologic landscape precludes anything but extreme physical activity.

In Salt Lake City, in northern Utah, the streets are scaled to the turning radius of a team of mules and a pack wagon, producing a grid with blocks 1/8 mile in length and decidedly unwelcoming to pedestrians.

There were highly organized power walkers in Colorado Springs, but they turned out to be cadets marching in formation through “the terrazzo” at the heart of the Air Force Academy.

Military discipline has never seemed as seductive as on that campus, designed by Walter Netsch and SOM in the mid-50s. I kept thinking of a line from an old Joe Jackson song: “you can wear the uniform and I can play along.”

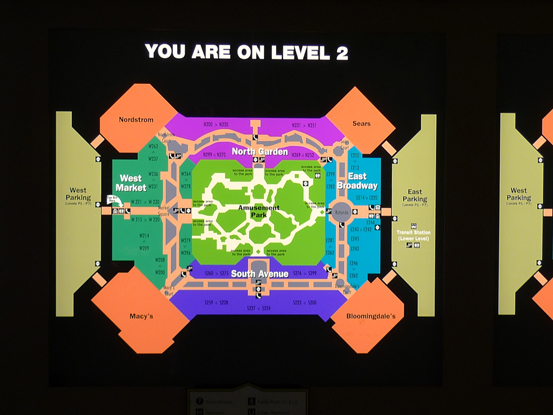

At any rate, I started to notice the the power walkers again as I got closer to the middle of the country. With 2.5 million square feet, the Mall of America near Minneapolis is so large that even most the casual shopper is transformed into a power walker.

It takes a certain amount of exertion to get all the way from Nordstrom’s to Bloomingdales to Camp Snoopy, even without a grade change.

It takes a certain amount of exertion to get all the way from Nordstrom’s to Bloomingdales to Camp Snoopy, even without a grade change.

At a bridge between the parking garage and the mall, an advertisement for BlueCross and BlueShield of Minnesota acknowledged this fact. The Gruen effect becomes a cultural condition.

Once I crossed the Mississippi the power walkers emerged in force. At the John Deere World Headquarters in Moline, Illinois they were doing laps in the visitor pavilion of the Saarinen-designed campus (1964) at the very beginning of the work day.

I wondered why they weren’t outside since Hideo Sasaki’s landscape is full of mature shade trees and winding paths. Perhaps they liked the building too much to leave.

When I was in downtown Moline the cashier at the John Deere gift store asked me if I had been out to the HQ and told me that her mother “had the privilege of working in that beautiful place for nearly twenty years.” So maybe those John Deere power walkers were diehard modernists, you never know.

Nearly 300 miles down the river from Moline, and right across the river from St. Louis, I stopped off to see the remains of the civilization at Cahokia (950-1200 AD). The Monks Mound, at the heart of the grand plaza, is the largest earthwork in the Americas. It rises to a height of 100 feet and its base covers fourteen acres. When I got there in the early evening it was still quite hot so I walked slowly up the stairs on the south face stopping at each terrace to admire the view and wipe the perspiration from my face.

Each time I paused I was lapped by a fast walker flexing barbells with each step. With her white sweatpants and orange t-shirt, she looked marvelous against the green grass and the blue sky, but it was her re-purposing of the ancient monument that I appreciated the most.

Looking at the St. Louis Arch from the top of the mound, I thought of Lewis and Clark and the opening of the west. Cahokia used to be the frontier; now it’s a para-fitness course.

POST-SCRIPT: In the middle of writing this, I spotted more power walkers. Up with the sun, they were making their way through a sidewalk-less subdivision in central Ohio, taking advantage of the coolness of the morning. I stopped counting at 22.