Shag 31 January 2011 No Comments

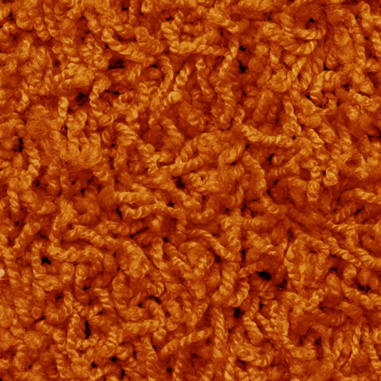

Last week I found myself debating the merits of orange shag carpeting with the president of my university. I’m not quite sure how a conversation about burying power lines veered into one about 1970s interior design, but afterwards my thoughts kept returning to shag.

In 1970 we moved to Cincinnati into a big stone house from the early 1920s. My parents bought the place from a couple with an affinity for shags which they installed wall-to-wall all over the house, with increasing garishness on each floor.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

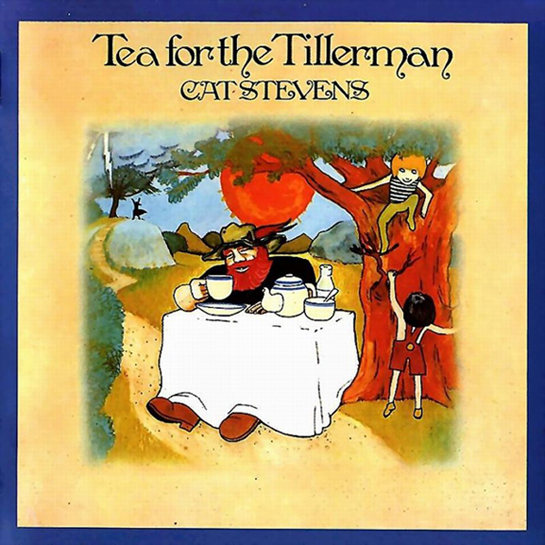

The shag in the first floor living room was only a shade darker than the harvest gold appliances in the kitchen and it provided a pleasing background for the LP cover art I admired while sitting in front of the hi-fi.

The shag in my sister’s 2nd floor bedroom was deep red. The acrylic threads were dense and irregular, just right for rolling a toy lunar rover and pretending it was the surface of the moon.

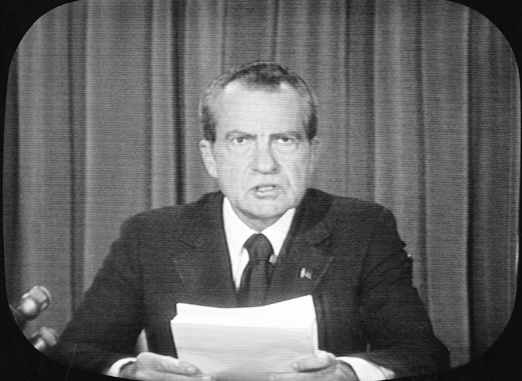

The shag in the wood paneled rec room on the third floor was bright orange. The color was a startling contrast to the dark green ping-pong table that filled the center of the room, but it was perfect for stretching out and watching TV, which I remember doing quite clearly on an August afternoon in 1974 when my mother called me upstairs to watch Nixon resign the presidency.

We moved out of that house a few weeks later (this had nothing to do with Tricky Dick), and my relationship with shag came to an abrupt end. Our next house had no wall-to-walls and certainly no shags, as my parents’ refined taste tended towards Orientals. But there was always a vague longing and in 2010 I finally got back together with shag.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

Sadly, though, my current shag is not orange; it’s a restrained light blue, a set of Flor tiles called “frost.” Only the style name, Rake Me Over, is a vague nod to the outré sensibilities of the swinger decade. Or it could be the title to a song by Elvis, something with an “All Shook Up” groove.

Elvis liked his shag. The Jungle Room in Graceland is a veritable monument to shag.

There are deep-pile green shags on the floor, on the walls, on the ceiling.

Originally, Graceland itself was little more than a slightly aggrandized center hall colonial, built in 1939 on the suburban outskirts of Memphis. Elvis expanded it gradually over two decades and the Jungle Room is part of the addition that commenced after he bought the place in 1957. Though Elvis was working with decorator Billy Eubanks by 1970, credit for the interior of the Jungle Room, which was completed by 1964, is generally ascribed to Elvis himself.

In the standard highbrow reading, Graceland is a temple of über kitsch and the Jungle Room is its holy of holies. But once you’ve actually been there, the plastic plants, artificial waterfall, ceramic monkeys, smoked mirrors, and all that shag are somehow touching. They seem more aspirational than gaudy—the fulfillment of the American Dream for a white trash kid from Mississippi.

Nonetheless, the green carpeting on the walls and ceilings stays with you. Not because it’s kind of tacky but because it seems, somehow, to cross the same boundaries as Elvis’ early music and performances, upending the proprieties of mid-century, mid-American domesticity.

Nonetheless, the green carpeting on the walls and ceilings stays with you. Not because it’s kind of tacky but because it seems, somehow, to cross the same boundaries as Elvis’ early music and performances, upending the proprieties of mid-century, mid-American domesticity.

As it turns out, Elvis was not alone in his carpet transgressions. Neatly bookending the Jungle Room are Paul Rudolph’s A+A Building at Yale of 1963 and Philip Johnson’s Art Bunker at the Glass House of 1965.

In the A+A lecture hall, the floor’s orange high-traffic carpeting runs seamlessly a few inches up the walls. This isn’t that unusual; linoleum was often installed this way in the 1930s in a streamlined elimination of the baseboard. But Rudolph went further and used the same carpet on the seating as well. This intensifies the presence of the orange against the finely crafted exposed concrete, both the smoother surfaces flanking the center aisle and the bush-hammered corrugations of the outer walls.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

The overall effect mediates the room’s horizontality and verticality, creating a kind of spatial continuum, a mid-century condition that George Wagner usefully analyzed in his 2002 Perspecta essay, “Ultrasuede.”

In the Art Bunker, the carpet is everywhere EXCEPT the floor.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

Passing into the vestibule from the Treasury of Atreus entrance you feel like you’ve stepped into a high-style cave, and one wonders if Johnson visited the Underground World Home Corporation’s model dwelling not far from his NY State Pavilion at the ’64 fair in Queens. Here in New Canaan, in combination with the low ceiling, the carpeted walls are utterly enveloping.

In the main space, the John-Soane-meets-Maltese-temple gallery, Johnson carpeted the rotating floor-to-ceiling panels that display his painting collection. The neutrality of the carpet’s buff color is undermined by its shaggy texture, but somehow this enhances the pictures.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

I could draw some big conclusion about rebels and iconoclasts and 20th century taste, but I won’t. Thinking simultaneously about the carpet predilections of Rudolph, Johnson, and the King is more than enough.

Bexhill or Bust 24 January 2011 No Comments

The other day, early in the new year, I walked to the sea. Though Irving Berlin was playing in my head–“I joined the Navy to see the world, but what did I see, I saw the sea”–I was far removed from Tin Pan Alley and this was no regular jaunt to the water. Instead of take-the-Garden-State-Parkway-to-south-Jersey-park-the-car-in-a-lot-just-west-of-the-boardwalk, it was put-on-your-wellies-and-tromp-through-the-mud-wondering-if-you’ll-ever-see-the-sun-again. In other words, I was looking at the Atlantic from the other side of the pond.

I wasn’t actually wearing wellies; my snow boots were a necessary substitute given the blizzard that hit the UK just before Christmas. Nor was it the sea that inspired the walk. I’d already admired the Channel on this trip and had the distinct pleasure of encountering horses on the beach rather than the SUVs I’d expect to find in the off season at home.

While we had a fixed destination, what inspired the walk was the walking itself. Thoreau regarded walkers as “an ancient and honorable class.” Sauntering down country lanes, climbing over rustic stiles, marching across planted fields and open pastures–all on public footpaths–it was easy to believe we were engaged in Henry David’s “noble art.”

Thoreau claimed that he was unable to preserve his health and spirit unless he spent at least four hours a day a foot; my three hour walk was a vacation extravagance. That may be an overstatement since it was more accurately a busman’s holiday: this architectural historian was headed to Bexhill-on-Sea to see an icon of British modernism.

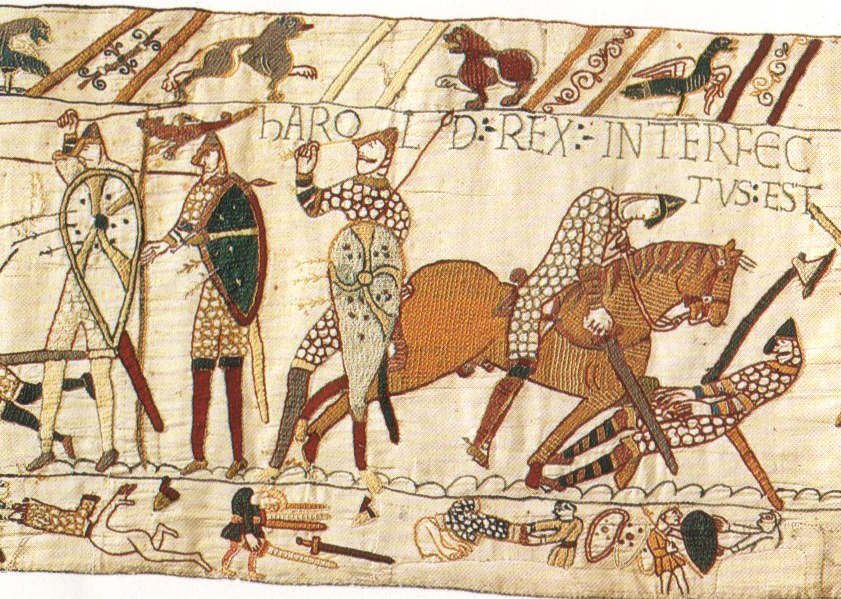

There was a whole lot of history to take in before we got there because our route was a spur of the 1066 Country Walk. We crossed the fields where the Battle of Hastings took place and admired the abbey that William the Conqueror built afterwards, supposedly on the exact spot where Harold II was cut down in battle. I remembered this scene from the Bayeux Tapestry.

Even without the fallen knights, it was pretty impressive.

.. .

……….

As we walked along I tried to figure out what I knew about the Norman Conquest before I saw The Norman Conquests, a BBC version of Alan Ayckbourn’s trilogy having been broadcast on PBS in 1980. Though the medieval battle is connected only eponymously to the drawing room comedy this was enough to prompt my teenage self to research the former in order to understand the pun of the latter. What could I have consulted in those pre-wikipedia days? The Encyclopedia Britannica would have required a trip to the library. My father’s copy of Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation seems more likely. This may be an entirely false memory, but I like the symmetry of one BBC TV show prompting me to look up something in a book based on another BBC TV show, particularly because at that point in my life my professional aspirations tended in the direction of network television programming.

Such thoughts were fleeting as we walked hill and dale; the pastoral landscapes were too distracting.

Like a Brit strolling through Tuscany in a Merchant Ivory picture, I wanted to proclaim truth and beauty beyond every copse. Happily our arrival on the outskirts of Bexhill brought such reveries to a conclusion before they became embarrassing. The subdivisions were as unlovely as the traffic was congested, but before too long we found ourselves on a wide street that led directly to the seafront.

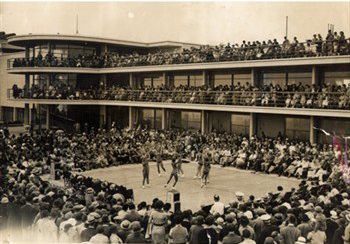

The older resort buildings show the long influence of the Brighton Pavilion, thirty miles west and a century older than the one we’d come to see. After an £8 million restoration the De La Warr Pavilion looks as crisp and white as it must have on the day it opened in 1935. Some might find the Serge Chermayeff and Erich Mendelsohn design a little too doctrinaire, but this is my kind of wear it on your sleeve modernism.

………………………………………………………..

From the curtain wall to the cantilevered stairs to the ribbon windows to the piloti to the burnished chrome plating, the building bristles with architectural optimism.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

In the 1930s this was meant to be a bright spot in the Depression decade. In the 2010s it still seems to work that way, though maybe it was just how the pavilion looked in the sun. After walking eight miles in the gloom, the clouds parted as we reached the water, adding a bit of contrast to my flat photographs and a bit of dazzle to my first impressions.

Bexhill, it turns out, gets four more hours of sunshine per week than other seaside towns–or so the local tourist bureau claims.

A Tramp Abroad, but mostly at Home 7 August 2010 No Comments

In A Tramp Abroad, Mark Twain reccounts his 1878 journey through Europe with his characteristic, and occasionally annoying, curmudgeonly humor. Late in the book, after too many months of fine dining and hotel fare, Twain is clearly longing for “American food and American domestic cookery.” In Chapter XX (pp. 235-241), he launches a mild attack on European food, from breakfast to dinner, and prepares an extensive menu for the distinctly American meal that he intends to eat upon his return to the States. For those interested in the particulars of this meal, I recommend Andrew Beahrs’ engaging recent book, Twain’s Feast, in which the author track’s down many of the American dishes that Twain describes.

Reading Beahrs’ book set me thinking about my own food adventures, recently abroad, but mostly at home. And just as I was contemplating a fantasy menu of my own, a friend emailed to ask when American Road Trip was going to post a food update comparable to last week’s building slide show. It was a fair question; I’d taken nearly as many pictures of food on my road trips as buildings. This shouldn’t come as a surprise. As loyal readers of American Road Trip are well aware, I hold food and buildings in equal esteem. If it seems that I sometimes privilege buildings over food, that’s only because buildings are my day job.

Upon reflection, I’ve come to realize my taste in food precisely mirrors my taste in buildings.

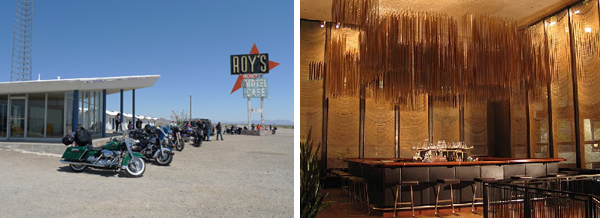

I prefer the extremes of vernacular and high style to the dreaded middle ground, tacos at a Route 66 gas station and abandoned motel having an appeal equal to martinis at the Four Seasons in the Seagram Building (which is being lovingly restored by Belmont Freeman Architects). No doubt, this appeal is inextricably linked to what I see as a direct, formal relationship between food and building, one that can have a powerful effect on dining.

Thus, for example, no matter how excellent Thomas Keller’s dishes, my enjoyment of Per Se is muted by the taupe blandness of by Adam Tihany’s interiors. Only the fake double doors of the restaurant’s entrance offer any kind of aesthetic frisson, but only because they remind me of a 1950s jewelry store I recall from my youth.

With those glossy blue doors, sliding glass partitions, and manicured topiaries, the stylized Dorothy Draper glamour of the entrance (which is little more than an interior store front in a shopping mall) is far more enthralling than the supposedly soothing serenity of the dining room itself.

To emphasize the food:building analogy I seem to be proposing, I was tempted, in the slideshow that follows, to include images of both the dishes I consumed and the spaces in which I consumed them. In the end, though, I decided that the food was ready for its close-up. Nonetheless, there are plenty of hints of the settings incidentally captured in photographs otherwise concerned with the fine details of cobblers, hamburgers, etc. Captions give some additional information for those who might want it.

Here is Mostly at Home on the YouTube channel AmericanRoadTripNYC. La cena e pronta.

At present I am a sojourner in civilized life again 27 July 2010 No Comments

Not surprisingly, my “life in the woods” was far less literal than Thoreau’s, involving little isolation and only fitful removal from my neighbors. Still, there was sufficient labor (more intellectual than physical) to keep me away from this particular place (my sadly static URL) for more than half a year. But unlike Henry David, I will display no false modesty about obtruding my affairs so much on the notice of my readers. After all, why go to all this trouble if not to obtrude? Isn’t obtruding a condition of life in the 21st century (at least in the developed world)? Indeed, it is my greatest hope that I will successfully obtrude, at least on a weekly basis, on the notice of my readers, whoever and how few they may be.

In the meantime, I relinquish the possibility of recouping my life in the woods with the same careful attention to daily minutiae and regular philosophizing found in Walden’s 200+ pages. Ongoing labors (and perhaps an insufficient dedication to transcendentalism) simply do not permit it. Nonetheless, some accounting is required.

Let this poor animation suffice: Since January, on AmericanRoadTripNYC, a new YouTube channel.

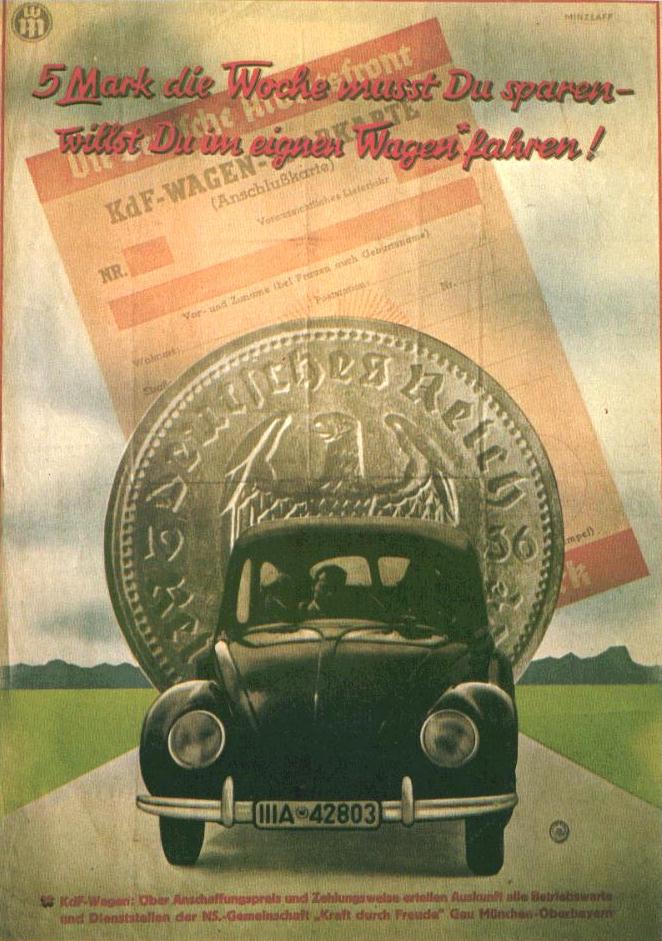

El Vocho 7 January 2010 No Comments

When I was growing up our cars were transportation, not lust. According to family lore, when my father was a soon-to-be-married young man he used his savings to buy a plot of land instead of a 1958 MG. The family cars that followed were unusual by the standards of 1960s America, but they were hardly objects of desire.

I don’t remember much about the Anglia, except that it was some sort of British Ford. Two Peugeots came after, not counting the gold Buick company car that came with my father’s organization-man lifestyle in the early 70s.

The first Peugeot was a 404 with a 4-speed column shifter that cried out for driving gloves. That car was burgundy with a matte finish and it had tailfins the way France had rock and roll, kind of groovy but a pale imitation of the real thing.

The second Peugeot was more conventional: a four-door sedan with a floor-mounted shifter and a sloped but squared-off rear; it was notable only for its paint job: a subtle metallic color called Cascade Green. It only looked green in the right light, and even then what your eye perceived was just a hint of sea foam—imagine Scope mouthwash diluted with five parts water.

The first car that was really mine, and that really caught my fancy, was a 1972 Volkswagen Beetle.

Bought at least a decade before “pre-owned” entered the lexicon, this faded yellow bug was a stripped down model, not a superbug. It had a flat windshield and four-on-the-floor with an AM radio and so much body rust underneath that the driver’s seat sagged towards the ground. Without a piece of cardboard on the floor, I could look down and see the blacktop, in a close approximation of Fred Flintstone’s motoring style. Though this induced vertigo at high speeds, driving the interstates of the northeast, between Philadelphia and Northampton, was always thrilling.

Once, I left the yellow bug at school over winter break and returned at the start of the spring semester to find it buried under two feet of snow. I dug my way in with a broom and had to use a hairdryer on the frozen lock. I put the key in the ignition and, just like the scene in Sleeper where Woody Allen finds a 200-year-old VW in a cave, the air-cooled engine turned over on the first try.

Sadly, my bug died soon after, though with great flare. In a catastrophic engine failure, it spewed oil all over the eastbound lanes of the Mass Pike on a final road trip to Boston just after final exams at the end of my senior year. I don’t remember ever having sex in the back seat of that bug (though I did stuff a queen size futon in it once), but thinking about it produces the same sort of romantic haze that accompanies so many male automotive reveries.

Though I didn’t realize it at the time, that Volkswagen was my real introduction to serious design, and all the social and political baggage that comes with it.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

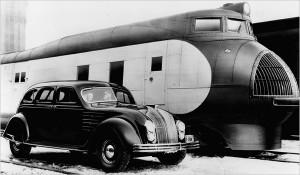

Perfected by Ferdinand Porsche and Erwin Komenda with the financial backing of the Third Reich, the body of the Type 1 Volkswagen was an unmistakable product of late 30s styling. It had much in common with Carl Breer’s Chrysler Airflow and Hans Ledwinka and Paul Jaray’s Tatra T77.

.

..

.

..

Like them, the VW was an early attempt to create a car body that was aerodynamically efficient, or at least looked like it was. Because the VW’s bulbous body became so familiar, so iconic, in the second half of the twentieth century, folks stopped noticing its streamlined details a long time ago.

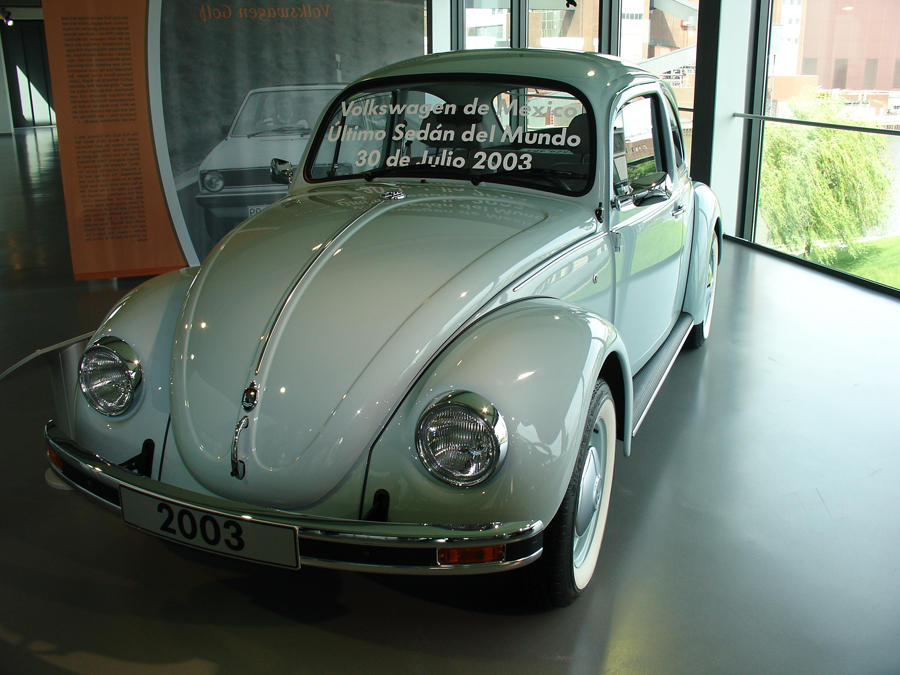

But they were there when the first production VW hit the streets in 1938 and they were still there when the last Type 1 rolled off the assembly line in 2003, nearly twenty-two million inverted teardrops, contoured fenders, and chrome speedlines later.

I’ve been thinking about VWs because I spent the holidays in Mexico, including a night in the city of Puebla, where the last Type 1 was built, in a factory that opened in 1954 after German immigrants to Estado Puebla lobbied Wolfsburg to begin Mexican production.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Aside from talavera tile and mole, VWs must be Puebla’s most culturally significant export.

That original plant is still in operation: modernized and re-tooled, it’s the only factory that produces the much-hyped, though ultimately underwhelming, new Beetle. (The debut of the Concept 1 prototype in 1994 occasioned my first and only purchase of Car & Driver and Road & Track.)

Touring Puebla at the end of 2009, it seemed clear that building beetles, like being declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was making a serious contribution to Puebla’s economic prosperity.

While wandering through a gentrifying indigenous neighborhood outside Puebla’s centro histórico, I discovered the familiar VW logo on all the street signs, corporate PR in the service of a barrio’s rebranding campaign.

Mostly, though, it’s the bugs themselves that make the biggest impression, whether in sleek black or tricked up for a fiesta.

Everyone knows that VWs are legion in Mexico but it was still a wonderment to see so many of them, especially in the capital where their broad metallic curves make a fine roving counterpoint to the churrigueresque ornament that’s as ubiquitous on the buildings as the bugs are in the streets.

I’m not sure if it was Christmas, or nationalism, or just standard color options, but there were green, red, and white bugs everywhere I turned.

.

.

.

.

.

.

And I can honestly say that they filled me with as much joy as freshly baked roscas de reyes (also green, white, and red) and freshly fried churros.

.That last bit might be a slight exaggeration because those were damn good churros. I’m sure it is no coincidence that they were served up at churrería as old as the VW itself.

El Moro opened in 1935 and, unlike Volkswagen, its proprietors have had the good sense to leave well enough alone. The churro, like the bug, is perfect in its original form.