The Hut, part i 15 March 2011 No Comments

After a gap of many years I recently returned to teaching the origins of architecture in an undergraduate history survey. I still call this course “caves to cathedral,” but I don’t actually begin with caves. In fact, my first lecture starts with the Seagram Building, but I’m still considering a new nickname: “hut to Bauhütte.” The alliteration may not be as satisfying as in “caves to cathedrals,” but it gives the hut pride of place.

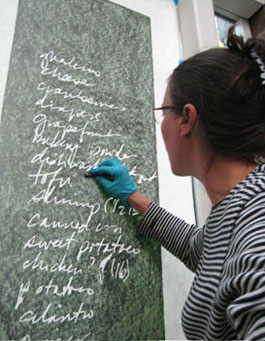

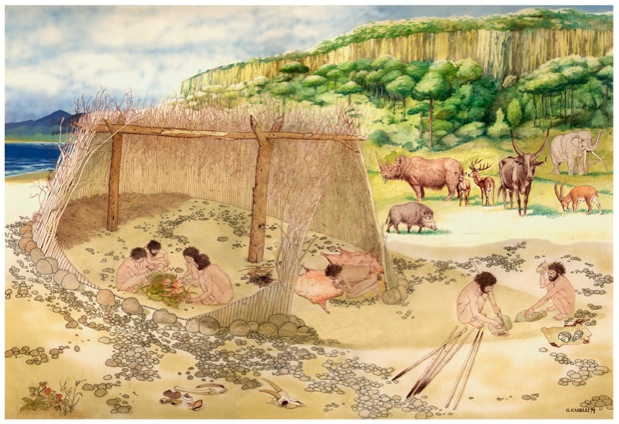

Around 300,000 BCE Paleolithic homo erectus returns each spring to the same spot in the south of France, near Nice. There, homo erectus builds a hut from palisaded branches and bark, securing the foundation with rocks. The hut is severely furnished: a sleeping area, a work area, and a hearth are all that are needed to satisfy the mobile lifestyle of the Paleolithic period. Henry de Lumley, the archeologist who discovers the encampment, calls the site terra amata, or beloved earth, perhaps acknowledging that the original hunter-gatherer foresaw the marketing potential of the Mediterranean. Though archeologists have since argued that Lumley’s enthusiasms overwhelmed his empiricism, “la hutte terra amata” is still regarded as one of the earliest human-made habitations.

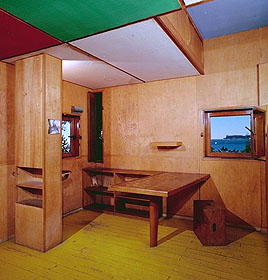

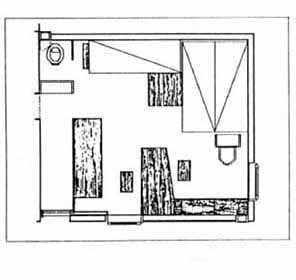

Awhile later, in 1952, and not far away, at Roquebrune-Cap Martin, Le Corbusier builds a hut for himself as a final retreat at the end of his life. Like the prehistoric visitors who preceded him, Corbu returns each spring, until his death in 1965, to a petit cabanon, a 12’ x 12’ square, wood-framed and lined in plywood. The cabanon was originally to be clad in sheet metal, a modest exercise in machine age modernism that recalls the architect’s early fascination with the automobile and the train compartment as models for machines à habiter. At the last minute Corbu substitutes split logs for the exterior and, thus, transforms his cabanon’s architectural aesthetic. Now, the cabanon reflects the brutalism Corbu prefers in his later career, along with his disenchantment with the industrial age, its waste, its pollution, its material excess.

The existenzminimum of the cabanon’s interior includes a precisely arranged toilet, table, cupboard, and bed. The arrangement owes less to the economy and simplicity of the assembly-line mass production that inspired the radical architect Corbusier once was than to the economy and simplicity of the 18th and 19th century philosophical traditions that inspired the romantic dreamer he never ceased to be. These are just musings. For a full description see Deborah Gans’ excellent Le Corbusier Guide.

Next: Huts in the Land of Lincoln.

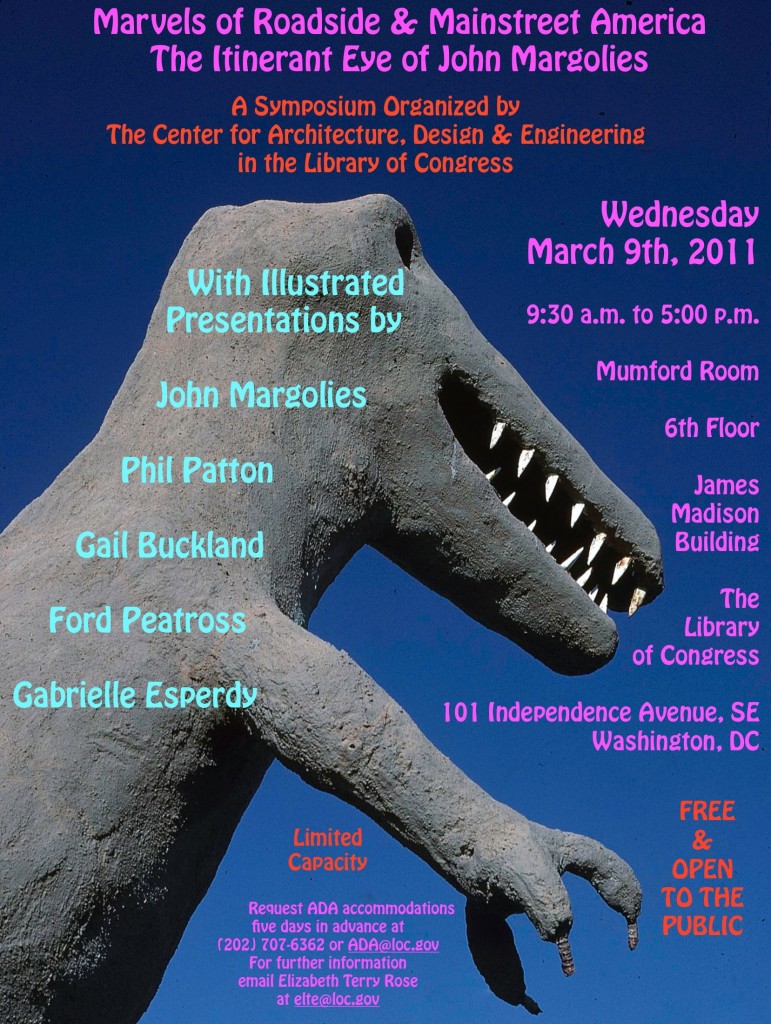

Margolies Mainstream and Marginal 8 March 2011 No Comments

Ducks, decorated sheds, ugly, ordinary, heroic, monumental, interstates, Main Street, Route 66, the Strip, White Towers, the End of the Road, Learning from Las Vegas, the Architectural League, Wayne McAllister, the Sands, the Fontainebleau, the Rat Pack, Ant Farm, Archigram, Telethon, Warhol, the Factory, Pop, postmodernism, Mies, Rudolph, Venturi, Scott Brown, Nam June Paik, Ed Ruscha, Design Quarterly, Progressive Architecture, the Madonna Inn, the NEA, Tom Wolfe, Reyner Banham, Lucy the Elephant, hippies, puppies, the Orgasmitron, the Real Housewives of Orange County, Marshall McLuhan, Morris Lapidus, Muzak, mobility, zoomscape, LSD, television, Haus-Rucker, Superstudio, New Topographics, New Journalism, high, low, hamburger stands, gas stations, drive-ins, donuts.

They all come together in the talk I’m giving at the Library of Congress on Wednesday, March 9th to celebrate the Library’s acquisition of the John Margolies Collection of photographs and ephemera of the American roadside.

I could live here 25 February 2011 No Comments

An article in the New York Times about Derek Diedricken’s Gypsy Junker microshelter reminded me how much I like a hut myself. I didn’t really need reminding–I live with a large Scott Peterman photograph of an ice fishing hut in Maine (Sabbath Day Lake III, 1998)–but the article did get me thinking about how long huts have been an object of affection.

I’ve never actually had a hut to dwell in, but when I was a kid I thought it would be cool to turn the rotting garden shed in our back yard in Chestnut Hill into a room of my own. (That I already had a room of my own, that, in fact, I had always had a room of my own, never obtruded upon this fantasy.) That shed was a rough six-foot cube of corrugated sheet metal, just big enough for a riding mower, a wheelbarrow, and a couple of rakes. The walls were white; the doors were green; the floor was plywood. The shed was already there when we moved to the house in 1974. It’s rusty musty state undoubtedly increased its appeal.

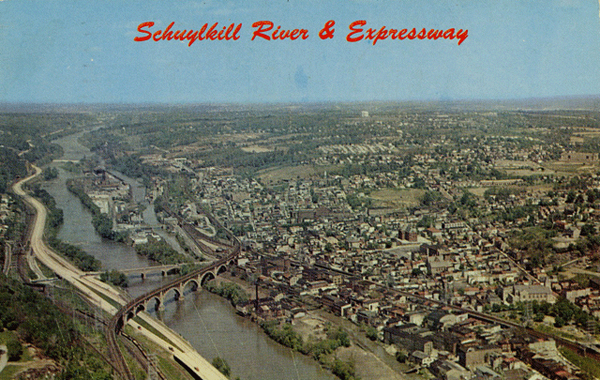

In high school I was fixated on a different shed; this one was also sheet metal but it must have been made of sturdier stuff, too, because it was raised a story off the ground, possibly above the railroad tracks, somewhere in Manayunk, close to the Schuykill and the old canal.

In the early eighties, Manayunk was still years away from gentrification and the shed was one small element in a much larger drosscape of abandoned factories, chain link fences, barbed wire, and hub caps. I wanted to live in that shed, too. I’m guessing the appeal there was the promise of a room with a view–post-industrial landscapes having a romantic quality even then.

In the early eighties, Manayunk was still years away from gentrification and the shed was one small element in a much larger drosscape of abandoned factories, chain link fences, barbed wire, and hub caps. I wanted to live in that shed, too. I’m guessing the appeal there was the promise of a room with a view–post-industrial landscapes having a romantic quality even then.

A few weeks ago, while visiting Thomas Edison’s Research Laboratory in West Orange, I decided that a room without a view would be good. Wandering around the complex with my colleague Matt Burgermaster (who’s been researching Edison’s concrete building patents), I was particularly taken with Vault 33.

Originally used to store molds for Edison’s phonographic cylinders, it’s a windowless concrete box, utterly plain but for an entablature-like cornice. This vestigially classical detail on an otherwise utilitarian structure is as charming as it is silly. Henry Hudson Holly was responsible for the design of a number of buildings on the site and it wouldn’t surprise me if this picturesque flourish was his doing. I could live with the cornice, but whether the the sensory deprivation quality of the interior would get to me, I’ll never know. Vault 33 is closed to the public because it’s still used to store a part of Edison’s archive.

Originally used to store molds for Edison’s phonographic cylinders, it’s a windowless concrete box, utterly plain but for an entablature-like cornice. This vestigially classical detail on an otherwise utilitarian structure is as charming as it is silly. Henry Hudson Holly was responsible for the design of a number of buildings on the site and it wouldn’t surprise me if this picturesque flourish was his doing. I could live with the cornice, but whether the the sensory deprivation quality of the interior would get to me, I’ll never know. Vault 33 is closed to the public because it’s still used to store a part of Edison’s archive.

So what is it about huts? They are “humble and iconic, insignificant and portentous, ephemeral and enduring.” Or so I thought back in 2003 when I did some research on them for an exhibition called Cabin Fever at the Ox-Bow School of the Arts. What I produced was a highly selective, idiosyncratically episodic architectural and cultural history of the hut. In other words, content perfect for posting here.

Coming soon: The Hut, parts i, ii, iii.

Valentine’s Day in Central Park 14 February 2011 No Comments

Walking through the park this morning I chanced upon the work of an urban romantic.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Just north of the Pool on a meandering path below the Great Hill, a rogue installationist wove a single long stemmed red rose through the slats of a park bench. Set against the dingy remains of multiple blizzards, the nearly perfect bloom appeared almost defiantly lovely.

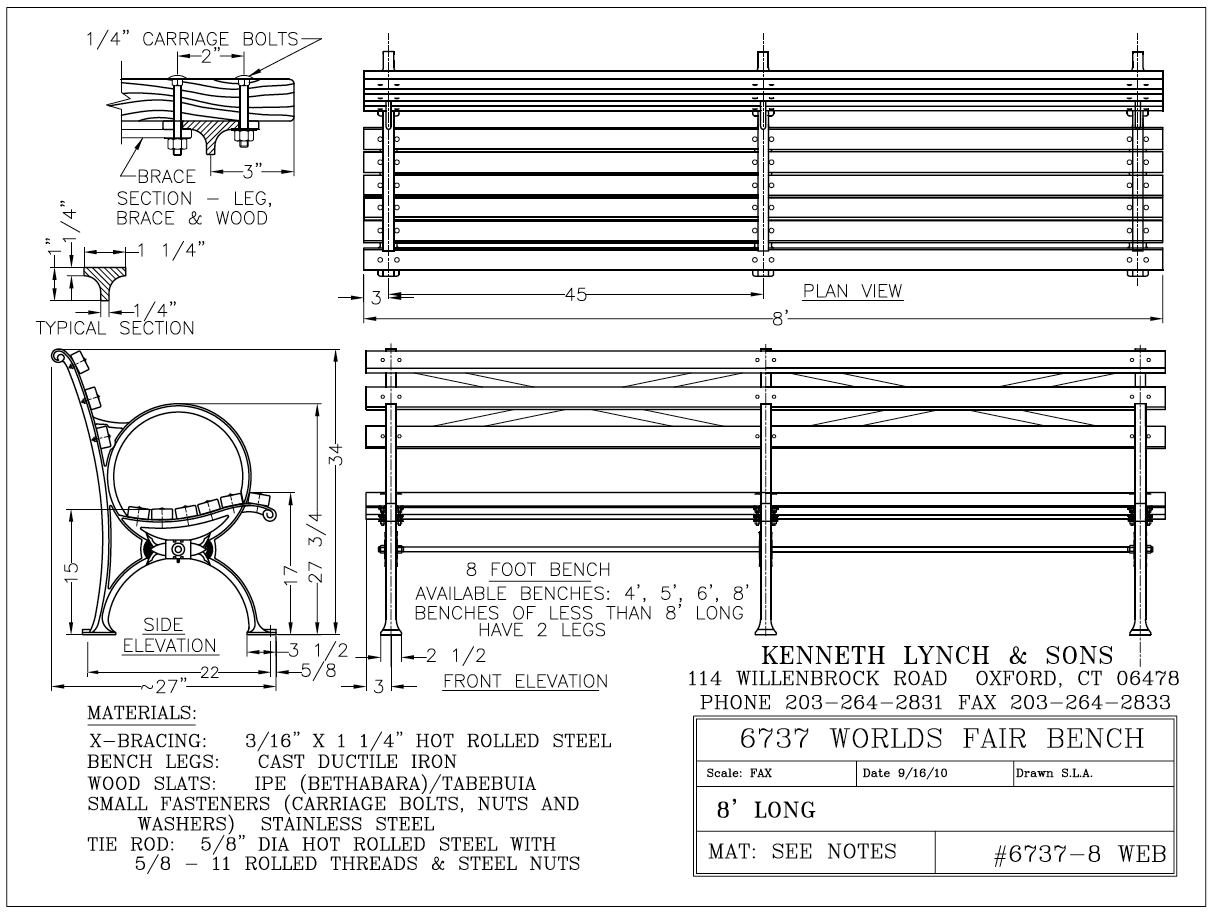

The bench is a 1939 World’s Fair model designed by a Connecticut blacksmith, supposedly in collaboration with Robert Moses himself.

Kenneth Lynch & Sons is still in business, and while the shop drawing on their website accurately conveys the technical specifications of the bench’s IPE wood slats, the notes fail to indicate how convenient they are as infrastructure for temporary floral arrangements.

Though the scale was more intimate and the effect more ephemeral, the rose installation reminded me of The Gates.

Perhaps the weaving of the rose through the bench slats was a gesture as utterly impulsive as The Gates were deliberately planned. I’ll never know because the rose person left no clues to his or her identity. But I’m certain of one thing: the artist responsible for the rose gave me nearly as much joy on this winter morning as Christo and Jeanne-Claude did six years ago this weekend, and I’m pretty sure it didn’t cost $21 million.

Books & Art 7 February 2011 No Comments

My friend Adriane Herman is an artist, curator, and associate professor of printmaking at the Maine College of Art. Her work is all about consumption and found imagery: 409 bottles, Little Golden Books, vintage postcards, discarded shopping lists, post-it notes, surplus bird seed. In Adriane’s work detritus and ephemera become art, not simply through object trouvé appropriation but through old-fashioned craftsmanship and technique, both analogue and digital.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

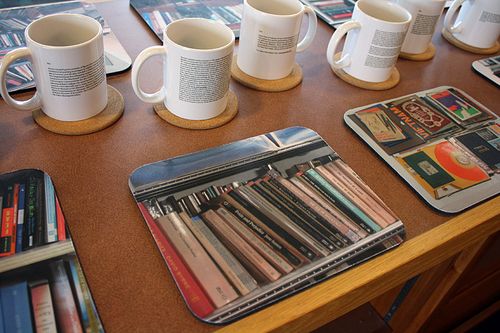

Her latest project is Plunder the Influence. As Adriane describes it, the project “examines physical manifestations and sources of influence”—in other words, she asked her collaborators to think about their books and send her photos and written vignettes reflecting their relationship to books. Over one hundred of us did. The results are astonishingly varied and utterly satisfying, whether they are viewed online or on mugs and mousepads in the “Storytellers” exhibition installation at Kate Chaney Chappell Center for Book Arts, located in the Glickman Library on the Portland campus of the University of Southern Maine.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

My own contribution is here. Browse The Stacks for responses from all of Adriane’s collaborators and see the Project Description for a full explanation.

On a related note, I’m reading Alexandra Horowitz’s Inside of a Dog which includes this Groucho Marx quip as its epigraph: “Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog it’s too dark to read.”