Frozen Confections Past 4 August 2011 No Comments

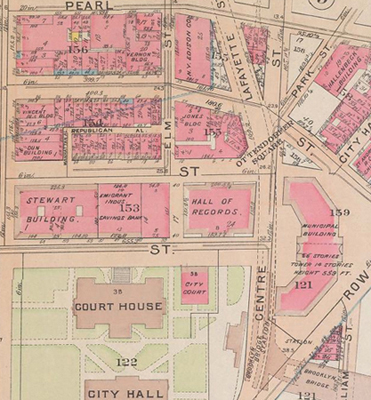

While I was on jury duty in July the Times published an article mentioning Wooly’s, a new shaved ice stand on Municipal Plaza, between McKim, Mead & White’s Municipal Building and Cass Gilbert’s U.S. (now Thurgood Marshall) Courthouse.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

In pre-Civic Center days, this was a continuation of Duane Street but it evolved during the Progressive era, first into Ottendorfer Square (named after the late editor of the New Yorker Staats-Zeigtung, whose offices were demolished to make way for the Muni Building) and then into St. Andrew’s Plaza. Today, it’s a brick-paved, pedestrian-only wedge that extends, sort of, the tangle of traffic islands and open areas that define the larger public space in and around Foley Square.

Heading over there on my lunch break at the beginning of the ignominious heat wave, I ignored the food-court-in-the-80s kiosks that were built there as a food-court-in-the-90s and made straight for Wooly’s bright blue and yellow stand. I ordered a Wooly (size), original (sweetened condensed milk flavor), finished with leche (syrup) and mangos (topping). On a hot afternoon, this was utterly refreshing and not as intolerably sweet as it might sound. Sitting there sweating while the shaved ice melted, faster than I could eat it, my mind wandered towards frozen confections of summers’ past. This wasn’t really Proustian; let’s call it Mr. Softee sentimentality.

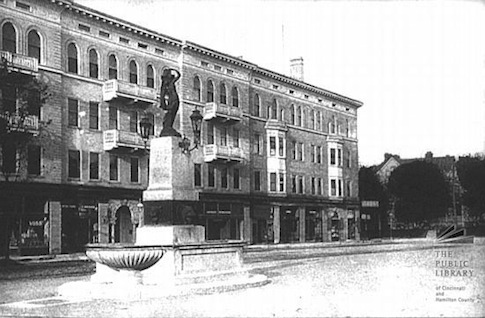

If these reminiscences had been chronological they might have started with chocolate chip ice cream from Graeter’s in Cincinnati. The store in Hyde Park, where I went as a kid in the early 70s, is one of the oldest outlets of the venerable chain (founded 1870).

You’d never know that from its modernized storefront, which sports a mid-1960s zig-zag canopy that, to quote the critic Russell Lynes in high dudgeon about a very different building, “would not look out of place on a bowling alley in Paramus.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

But that’s why it looks so good on an aging ice cream parlor in Hyde Park Square, a genteel shopping district built in the 1890s to serve one of Cincinnati’s most exclusive streetcar suburbs.

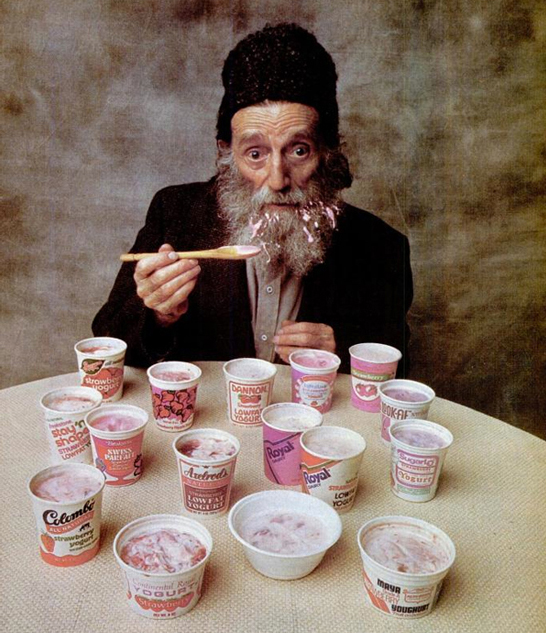

Another significant frozen confection experience took place in New York just a few years later. 40 Carrots in Bloomingdales opened in 1975 in response to two seemingly unrelated trends.

The first was an expansion in yogurt consumption throughout the metropolitan area sufficient enough to rate a feature article in New York Magazine. The second was Bloomingdale’s transformation from a dowager department store into an epicenter of urban trendiness.

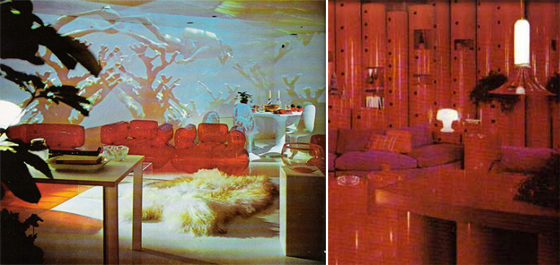

As supervised by the store’s president, Marvin Traub, this included the identity and graphics program by Massimo and Lella Vignelli that produced the now legendary brown bag series. It also included an interiors and retail renovation program that replaced stalwart departments with small, ephemeral boutiques, like those overseen by Barbara D’Arcy, the store’s influential design director for much of this period.

Her work certainly influenced my mother’s decision to purchase a Kartell Componibili unit (Anna Castelli Ferrieri, 1969) for her bathroom—a rare concession to contemporary design in the otherwise traditional décor of my parents’ house. By the mid-70s, Bloomingdale’s restaurants were subjected to the same formula as its boutiques.

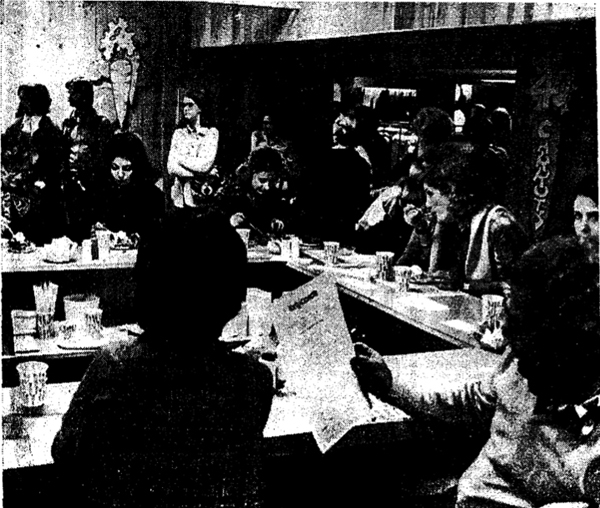

Originally, 40 Carrots consisted, soda fountain style, of just 12 stools and a counter, but it was so successful that it expanded three times in as many years. I don’t recall the space exactly but remember it as evoking a sort of health-food-made-stylish urban chic.

It comes as a surprise, therefore, to read in Mimi Sheraton’s 1976 New York Times review that the décor of 40 Carrots included knotty pine boards and dancing carrot cartoons. It’s the soft serve frozen yogurt that looms large in my memory and somehow I’d managed to transfer the cool whiteness of the fro-yo to the space itself. How I managed to suppress the actual Moosewood vibe of the place for so many years remains a mystery, but my aversion to Birkenstocks may now have an obvious root cause. 40 Carrots still exists, by the way, in an enlarged and renovated space it moved into in 2007. Frozen yogurt is still the best selling item on the menu. It may be time for another visit.

Readers will be relieved to know that my reminiscences were neither chronological nor complete, skipping over many of the ice cream stores that followed: Herrell’s and Barts in Northampton, Gatsby’s in Montauk, Bob’s Famous in D.C., where I worked after college in a white brick building occupied by the Heritage Foundation. Sadly, I cannot report on the frozen confection predilections of famous conservatives; in D.C. in the 80s everybody dressed like a Republican.

A selection of more recent frozen confection experiences, in mostly chronological order:

Brad & Dad’s is in Palmyra, New York, the hometown of Joseph Smith and generally regarded as the birthplace of Mormonism, which may be more of an attraction for some people than the ice cream.

Birdsall’s Ice Cream in Mason City Iowa is nothing special, though it has some fine boomerang Formica countertops and is in better shape than Frank Lloyd Wright’s Park Inn Hotel and City National Bank building (1908-10), nearby.

This building, the reason we stopped in Mason City, is now in the midst of a much-needed renovation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The “concrete” from Ted Drewes in St. Louis lives up to its legendary thickness. Despite the heat and humidity of a St. Louis spring, not a drop melted into the parking lot.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.While it provided some measure of sustenance as we braved the long lines to get to the top of Saarinen’s Arch, we were hungry again by the time we got to the Wainwright Building.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The Red Rooster Drive-In in Brewster, New York is old-school chocolate dipped soft-serve dispensed from a building with a slightly swoopy, high-pitched roof, candy-striped pediment, and an ice cream shaped cupola–just what’s needed to catch your eye as you drive along N.Y. 22.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The Bridgehampton Candy Kitchen doesn’t have a cupola, but the Dan Flavin Art Institute nearby does—and the Flavins (which brought me to Bridgehampton to begin with) were a whole lot better than the ice cream.

Central Dairy in Jefferson City, Missouri occupies a fine glazed block box that is immaculate inside and out. Sadly, the ice cream is unexceptional.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

La Beau’s Drive-In in Garden City, Utah is the reverse. The building is unlovely, but the shakes, made with locally famous Bear Lake raspberries, are inspired.

Parkside Candies on Main Street in Buffalo occupies a two-story commercial building five miles north of downtown.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

It doesn’t matter that the sundaes are almost insipid, because the setting, designed by G. Morton Wolfe, is worthy of Garnier’s Paris Opera. Now that’s one place I’ve yet to have a frozen confection, though I read somewhere that they used to serve ice cream in the Salon du Glacier. I’d like to believe this is true but it’s probably a mis-translation by some hungry, hopeful scholar. And at any rate, who wants to eat ice cream in the 9th when there’s Berthillon in the 4th? For the record: I consumed my first dish of Berthillon sorbet in 1982.

“There were many of the modern American houses here.” 22 July 2011 No Comments

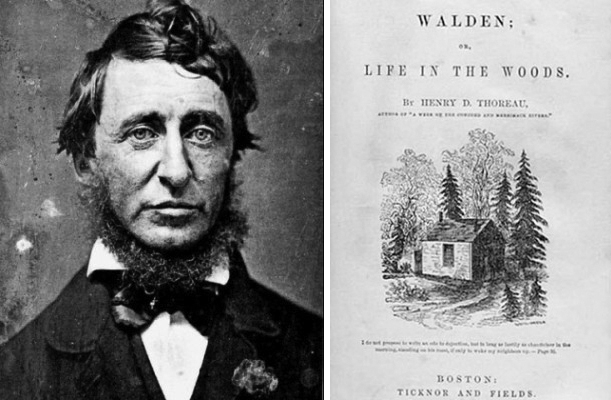

When Thoreau wrote those words in his book on Cape Cod (published posthumously in 1865), he didn’t mean it as a compliment. He had nothing but disdain for the “modern” houses he saw on the Cape, white painted boxes built of “dimension timber, imported from Maine.” (The italics are his.) Not surprisingly, given the romantic rusticity he displayed in Walden, Thoreau preferred the Cape’s “old fashioned and unpainted houses,” which seemed to him “more comfortable, as well as picturesque.” But if Henry David had returned to the Cape a century later he might have found modern American houses that were more to his liking.

I certainly did when I stopped off in Wellfleet in June to participate in a summer program of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust. In addition to giving a talk on the modern vernacular, I was invited to spend a few days in Charlie Zehnder’s Kugel-Gips House (1970), recently restored by the CCMHT and available to the public as a rental property that provides this small non-profit with vital income to support its programs. Working with the National Park Service, and under the energetic leadership of Peter McMahon, the CCMHT is rescuing, preserving, and studying modernist architecture on the Cape—a legacy that deserves to be much better known.

It stretches back to the 1940s, when Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Serge Chermayeff, and other recent European émigrés began to make summertime visits to the Outer Cape. In Wellfleet and Truro, in particular, these modernist luminaries mixed with local, self-taught designer/builders like Jack Hall and Jack Phillips.

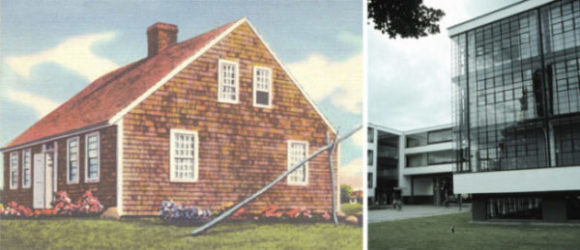

Early on, the two Jacks saw parallels between the New England vernacular and the new architecture in Europe, and they started making buildings—cottages and small commercial structures—that fused the two, combining the handcrafted materiality and modesty of a Salt Box with the structural openness and lightness of the Bauhaus.

Early on, the two Jacks saw parallels between the New England vernacular and the new architecture in Europe, and they started making buildings—cottages and small commercial structures—that fused the two, combining the handcrafted materiality and modesty of a Salt Box with the structural openness and lightness of the Bauhaus.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the cottage that Jack Hall designed and built in 1960 for Ruth and Robert Hatch, a painter and Nation editor, respectively. From afar, the cottage appears essentially of the place, a perfect embodiment of a seaside landscape, its battered boards and weathered frame as bleached and stained as a fishing pier. Up close, the cottage displays a modernist sort of formal rigor—well, as much rigor of form as a stick-built dwelling perched on pilings in the dunes can have. But that’s actually a good thing: the Farnsworth House it ain’t, nor does it pretend to be; it’s too intuitive for that.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Still, standing on the Hatch decks looking out into the dunes, one can’t help but think of Mies’ project for the Resor House and the way its structure consciously framed the landscape of the Tetons. And the cottage has other modernist affinities, too, with buildings as diverse as the Gropius house in Lincoln, Mass (especially the screened in porch) and, on the opposite coast, the Eames house in Pacific Palisades (in its potential for flexibility).

Here in Wellfleet, Hall designed a straightforward rectangular grid of wood, seven by five bays, and used it to define the cottage’s structure and its space. Each cube, or sequence of cubes, serves a particular programmatic need: terrace, living room, kitchen, bath, bedroom, studio, etc.

Open air corridors, also defined by the cubes, provide access to most of these spaces, their entrance doors shielded by the slight cantilever of three hovering roof planes whose presence is especially visible from the top of the surrounding dunes.

Open air corridors, also defined by the cubes, provide access to most of these spaces, their entrance doors shielded by the slight cantilever of three hovering roof planes whose presence is especially visible from the top of the surrounding dunes.

A series of moveable panels, operated by a rope-and-pulley system, do double duty as storm shutters and shading devices. Taken together, the frames, panels, and roofs give the cottage a kind of shaggy modularity.

The Hatch Cottage is the next house the CCMHT will restore, after it completes detailed documentation this summer. And the reason it needs to be restored is part of the complicated back-story of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

As the art and design circles of the Outer Cape intersected and widened during the mid-century decades, an astonishing number of inventive modern buildings were erected throughout the area, in the woods, on the ponds, above the dunes, and overlooking the bay and the ocean. This continued even after the National Seashore boundary was fixed in 1959, which meant that those post-1959 houses would eventually become the property of the federal government. Thus, the 1960 Hatch Cottage became Park Service property after Ruth Hatch died in 2004. Originally, the National Park Service intended to demolish these houses in order to “restore” the seashore to a more “natural” state (or as natural as a place can be when it’s been occupied by humans for thousands of years).

The history does not record whether anyone noticed that the NPS was proposing to tear down modern buildings on the Outer Cape at the same moment it was erecting modern buildings on the Outer Cape as part of its Mission 66 program.

Designed by Ben Biderman of the NPS Eastern Office of Design and Construction, the Salt Pond Visitor Center of 1964 is more conservative than many of its western contemporaries (those at Capitol Reef and Mesa Verde, for example), with its nearly symmetrical plan and ponderous, hexagonal central pavilion. The roof is a cross between Richard Burke’s Pizza Hut prototype (also of 1964) and a run-of-the-mill Howard Johnson’s from that same period, and it is tempting to push this parallel further given HoJo’s long history on the Cape, the chain’s second unit having opened in nearby Orleans in 1932.

Designed by Ben Biderman of the NPS Eastern Office of Design and Construction, the Salt Pond Visitor Center of 1964 is more conservative than many of its western contemporaries (those at Capitol Reef and Mesa Verde, for example), with its nearly symmetrical plan and ponderous, hexagonal central pavilion. The roof is a cross between Richard Burke’s Pizza Hut prototype (also of 1964) and a run-of-the-mill Howard Johnson’s from that same period, and it is tempting to push this parallel further given HoJo’s long history on the Cape, the chain’s second unit having opened in nearby Orleans in 1932.

The Visitor Center’s flanking wings are far more satisfying than the central pavilion: with their asymmetrical rooflines and contrasting shake and brick cladding they are simultaneously of the Cape and the modern era. Out there, in a place that Thoreau thought was “as wild and solitary as the Western Prairies” genius loci met the zeitgeist. And that’s what the Cape Cod Modern House Trust is working so hard to preserve.

Learning from Bletter 1 May 2011 No Comments

These are my opening remarks from the symposium I organized for Rosemarie Bletter, my Ph.D. advisor.

We are gathered here today to honor Professor Rosemarie Haag Bletter on the occasion of her retirement from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. And it is my happy task, by way of introduction, to spend a few minutes reviewing Rosemarie’s distinguished career as a scholar and teacher.

Rosemarie arrived at the Graduate Center in 1987, to teach in the Interdisciplinary Program in Modern German Studies and the Ph.D. Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures. Since 1990 she has been Professor of European and American architecture and theory of the 19th and 20th centuries in the Ph.D. Program in Art History.

Rosemarie was educated at Columbia University where she completed a master’s thesis on the Catalan Mondernista architect Josep Vilaseca and a doctoral dissertation on German expressionism and the architectural and planning work of Bruno Taut.[1] These two subjects helped define what have remained abiding interests throughout her career in scholarship and teaching dedicated to pushing the boundaries of canonical modernism to create not simply a more inclusive understanding of modern architecture but a more nuanced one.

The extended series of essays that came out of and built upon her dissertation, including “Expressionism and the New Objectivity,” “Interpretation of the Glass Dream,” “Paul Scheerbart’s Architectural Fantasies,” and more recently “Mies and Dark Transparency” (her contribution to MoMA’s Mies in Berlin catalogue) are meticulously crafted works of architectural history—combining archival research and socio-cultural contextualizing with sophisticated formal analysis, theoretical interpretation, and projective critique.[2] They are also models of positive historical revisionism that quietly—without rhetoric or bombast—insist upon an alternative and more complex telling of modernist narratives.

Rosemarie’s interest in exploring modernism’s diverse strands also informed her work as a curator. In Skyscraper Style at the Brooklyn Museum she offered a serious reappraisal of New York’s Art Deco towers, situating them as a distinct, but legitimate form of modern architecture.[3] In High Styles at the Whitney Museum of Art, she explored the impossibility of a single or dominant trend in American design in the 20th century, and examined the aesthetic gulf between elite and popular taste, especially where modernism was concerned.[4] These are issues she revisited in numerous exhibition catalogues including “The Myths of Modernism” for Craft in the Machine Age and “The Laissez-Faire, Good Taste, and Money Trees” for Remembering the Future.[5]

Shedding light on architecture’s plurality—exposing the existence of multiple modernist stories, indeed of multiple modernisms, may be Rosemarie’s most important legacy. And this may explain why much of her scholarship has a decided historiographic strain, as she worked to uncover the myriad ways that designers, critics, and historians constructed the modernist narratives that became her frequent subject. One of the best examples of this is her extended introduction to the English translation of Adolf Behne’s 1926 book The Modern Functional Building, published in 1996 in the Getty’s Text and Document series.[6] Her description of Behne’s critical project aptly characterizes her own, for Bletter, like Behne “unmasked many of the ideologies of functionalism, rationalism and European modernism.” Rosemarie’s unmasking was not, however, limited to Europe or to Modernism.

In “On Martin Frölich’s Gottfried Semper” she revealed how the 19th century theorist’s ideas about the relationship between form and style were misunderstood and misinterpreted by later theorists, from the Wagnerschule to the Chicago School.[7] In “The Invention of the Skyscraper: Notes on its Diverse History,” she explored the complexity of shifting attitudes towards this distinctive US building type, revealing how history and criticism transformed the workaday commercial tower of the late 19th century into an emblem of high architecture by the middle of the 20th.[8] Similar concerns remain in Rosemarie’s ongoing research. She is currently collaborating with Joan Ockman to prepare a critical edition of the proceedings of Modern Architecture Symposia held at Columbia in the 1960s. This project is aptly titled “Between History and Historiography.”

In challenging modernism’s grand narratives, foundational assumptions, and representational apparatuses, Rosemarie had much in common with those architects whose work in the 1970s and 1980s was identified, however problematically, as postmodern. And her writings on the work of architects like Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, and Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown reveal her to be a perceptive critic of present day practice. Time and again, in essays like “Transformations of the American Vernacular” and “Frank Gehry’s Spatial Reconstructions,” Rosemarie demonstrated the perspective and scope the historian brings to the project of contemporary criticism, including the ability to reveal how architects, to use Rosemarie’s own words, “superimpose their own predilections upon earlier theoretical frameworks.”[9]

Nowhere is this clearer than in Rosemarie’s concise 3-page essay on Five Architects, which remains, three decades after its publication, an exemplary analysis of the theoretical debates between the Whites and the Grays that dominated architectural discourse in the late 70s.[10] This same criticality is evident in the documentary films Rosemarie made with her husband, the critic Martin Filler, including The Architecture of Arata Isozaki and Beyond Utopia: Changing Attitudes in American Architecture, which, memorably, includes a scene of Denise Scott Brown standing in the Piazza San Marco demurring the notion that she and Venturi are post-modernists by explaining that “Marx was not a Marxist.”[11]

It was, of course, Rosemarie’s scholarly critique of postmodernism that led me to choose a building by Venturi Scott Brown to illustrate the poster and program for this event. As it turns out, the Best Products Catalog Showroom in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, designed in the late 1970s, was more appropriate than I realized. When the building was being torn down a few years ago, Bob Venturi called Rosemarie to ask if she wanted any relics. She said yes to four porcelain steel panels from the building’s decorative, wallpaper-like façade, which she apparently intended to hang in her apartment. This didn’t happen—not because of their size, or because the partition walls of her post-war building may not have been up to the strain of paneled steel, but because the panels’ stylized floral motif was not legible when viewed up close and in isolation. Rosemarie’s aesthetic sensibility has always been as finely honed as her critical one. These panels are currently installed here at the Graduate Center and they will make an excellent backdrop for photographs at the end of today’s event.

In this brief overview I have attempted to give you some sense of the breadth of Rosemarie’s work. In the interest of time, though, I have left out scores of important publications, papers, and lectures that add depth and texture to Rosemarie’s career as a scholar. Throughout that career Rosemarie brought her scholarly concerns to bear directly on her teaching—here at the Graduate Center and at the other distinguished institutions where she held faculty positions, including Columbia University and the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. The courses she taught ranged from visionary architecture to the museum as a social and cultural artifact, from early 20th century modernisms to post-modernism and beyond, from issues in 19th century architecture to the memorably titled class “from reconstruction to deconstruction.”

This afternoon’s talks give us the opportunity to see the influence of these and other courses on a generation of scholars, and I asked our speakers to be somewhat reflective today in order to highlight how their work with Rosemarie shaped their research methodologies and interests, and their overall intellectual development.[12] For my part, I can credit Rosemarie’s expansive view of modernism with helping me to methodologically situate my own scholarly proclivities, from modernized storefronts to Morris Lapidus. My current book project, Architecture & Autopia, looks at the ways that ideas about, and attitudes towards, the commercial landscape shaped architectural discourse after World War II in terms of practice, history, theory, and criticism. And it has been obvious to me from the start, that this project is utterly indebted to Rosemarie’s perceptive historiographic work, as well as her thoughtful criticism of Venturi Scott Brown.

Because of time constraints, we will hear today from only a few of the people who worked with Rosemarie over the years, but among her many outstanding students, one, in particular, merits special mention because she could NOT be with us. Loretta Lorance, who received her doctorate from the Graduate Center in 2004, died of cancer in February. Her dissertation, supervised by Rosemarie, examined the life and work of the designer technocrat R. Buckminster Fuller and became a well-received book published by MIT in 2009. Reviewing Becoming Bucky Fuller in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Felicity Scott noted how skillfully and convincingly Loretta “debunked the Fuller myth.” Those of you who knew Loretta will recall that she needed little prompting to debunk some one or something. But with Rosemarie’s guidance—Professor Bletter being a master of dismantling architectural hagiography—perhaps Loretta was able to knock Fuller off his self-constructed pedestal with more precision and scholarly authority than she might have otherwise.

Before introducing our first speaker, I’d like to thank both Kevin Murphy for his unstinting support of this event and Andrea Appel, Art History’s Assistant Program Officer, for her tremendous logistical help. I should also acknowledge Claire Zimmerman, who suggested several years ago that we organize something to honor Rosemarie, and whose enthusiasm for this event refused to be dampened by my repeatedly suggesting that perhaps we ought to wait for Rosemarie to retire. So here we are finally are Claire—I’ve managed the symposium; the festschrift is all yours. One final note for the students in the room, I will post a fully cited version of these introductory remarks on my website at esperdy.net—thus insuring Rosemarie’s influence on the NEXT generation of scholars.

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Josep Vilaseca i Casanovas: His Works and Drawings – A Catalogue Raisonné,” MA thesis Columbia University, 1967.

Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Bruno Taut and Paul Scheerbart – Some Aspects of German Expressionist Architecture,” Diss. Columbia University, 1973.↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Expressionism and the New Objectivity,” ArtJournal 43 (Summer 1983), 108-20.

Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “The Interpretation of the Glass Dream: Expressionist Architecture and the History of the Crystal Metaphor,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 40 (March 1981), 20-43.

Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Paul Scheerbart’s Architectural Fantasies,” 35 (May 1975), 83-97.

Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Mies and Dark Transparency,” Mies in Berlin, eds. Terence Riley and Barry Berdoll (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2001).↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter and Cervin Robinson, Skyscraper Style – Art Deco New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975).↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “The World of Tomorrow: The Future with a Past,” High Styles: Twentieth-Century American Design (New York: Whitney Museum of Art, 1985).↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “The Myths of Modernism,” Craft in the Machine Age, 1920-1945 (New York: Harry N. Abrams and the American Craft Museum, 1995).

Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “The ‘Laissez-Fair,’ Good Taste, and Money Trees: Architecture at the Fair,” Remembering the Future (New York: Rizzoli and Queens Museum, 1989).↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, Introduction to The Modern Functional Building, Text and Document (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Center, 1996).↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “On Martin Frölich’s Gottfried Semper,” Oppositions 4 (October 1974), 146-53.↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Invention of the Skyscraper: Notes on Its Diverse Histories,” Assemblage no. 2 (February 1987), 110-17.↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Transformations of the American Vernacular,” Venturi, Rauch & Scott Brown: A Generation of Architecture (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1984).

Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Frank Gehry’s Spatial Reconstructions,” The Architecture of Frank Gehry (New York: Rizzoli & the Walker Art Center, 1986).↵

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Review of Five Architects and ‘Five on Five’,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 38 (May 1979), 205-7.↵

- The Architecture of Arata Isozaki, Rosemarie Haag Bletter and Martin Filler, Blackwood Productions, 1985.

Beyond Utopia: Changing Attitudes in American Architecture, Rosemarie Haag Bletter and Martin Filler, Blackwood Productions, 1983.↵

- Mary Beth Betts, “Defining Modernism: Joseph Urban and the new School for Social Research.” _________________________________

Jeannette Redensek, “Josef Albers and Psychologies of the Non-Objective”

Claire Zimmerman, “Image into Building.”

Larry Busbea, “Paolo Soleri and the Non-Organic Life of Architecture.”

Deborah Lewittes, “The Shape of the City to Come: Regionalism and Urban Identity in Postwar London.”

Noah Chasin, “Learning from Lahore: Unexpected Postmodernism in Unlikely Places.”

PoYin AuYeung, “Relational Politics: Conflicts and Connections in the Redevelopment of Beijing.”

Barry Bergdoll, concluding remarks on Rosemarie’s scholarship and teaching.↵

Two final huts (except they are cabins) 9 April 2011 No Comments

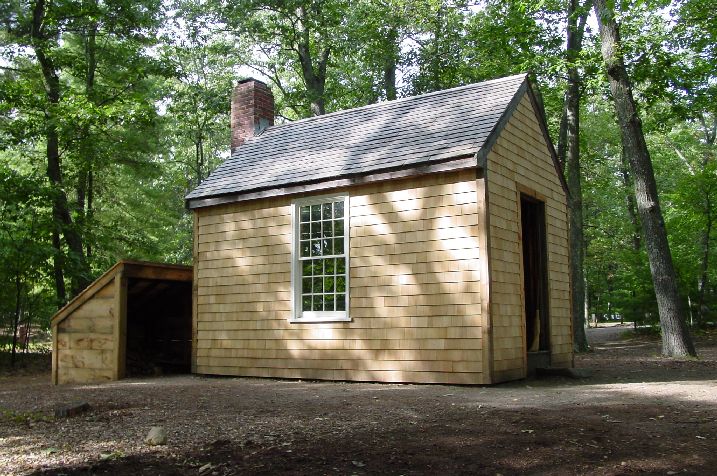

In 1852 the rustic cabin achieves immortality as a place to escape from one’s everyday life when Henry David Thoreau publishes an account of his self-imposed, semi-seclusion on the shore of Walden Pond from 1845 to 1847.

There he lived, mostly self-sufficient, having removed himself from “civilized life” to a house he built for himself for the economical sum of $28.12½ . His cabin was as much as a philosophical space as a physical one, as Thoreau freely admits. It is not enough to get away; to truly “live deliberately,” it matters how one does it. So, with a borrowed axe, Thoreau cleared a site and hews the timber to frame his new home. To roof and enclose the cabin, Thoreau purchased an Irishman’s shanty—he is untroubled that the Irishman and his family are still in residence—which he disassembles for its boards and shingles. His use of these recycled materials was intended to shock the reader, as much as his observation that the log huts of the poor are the most interesting dwellings in the country. With Victorian materialism coming into full flower, Thoreau was deliberately snubbing the nation’s cultural and architectural tastemakers by proclaiming the “unpretending” humble abode the most worthy of admiration and emulation.

Escaping to his cabin at Walden, Thoreau avoided, if only for a short while, those “lives of quiet desperation” to which we are fated. Alas, the same cannot be said of visitors to Thoreau’s (replica) cabin today: the parking lot is crowded and gift shop is full of tchotckes (I bought two bumper stickers).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Still, peering into the cabin you can sense how Thoreau intended to confront just life’s essentials, stripping away material excess to work simply, play simply, dress simply, and eat simply. This was the only life he believed he could possibly lead within the honest walls of his honest cabin. That the prophet of self-reliance had his mother do his laundry was kept a secret for many years.

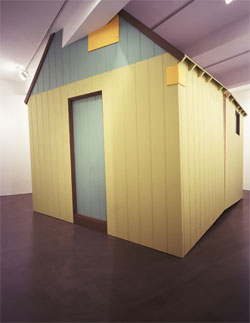

Around 1972, a different sort of philosopher built a rustic cabin for himself in the wilds of Montana. Theodore Kaczynski’s cabin is similar to Thoreau’s. It is small and simple, a single 10’ x 12’ room with a pitched roof; it is hand made of rough materials, plywood and tin; it has no electricity or running water. Like Thoreau, Kaczynski removed himself to the cabin to escape the pressures of civilization and begin what becomes his life’s work, writing a 35,000 word manifesto excoriating late industrial society and building letter and package bombs that, over the course of two decades, will kill three people and maim two dozen more.

When the FBI arrested Kaczynski as the Unabomber in 1996 (fifteen years ago this month), his remote dwelling was subjected to the harsh glare of the media spotlight. The rustic cabin’s most obvious virtues now became its most notorious vices: physical isolation is deviant; intellectual solitude is psychotic; living without modern conveniences is abnormal. In 1997 the cabin was loaded onto a flatbed and trucked to California where it was featured prominently in the Unabomber’s trial. Far more totemic than O.J.’s glove, the cabin in the courtroom was less a piece of evidence than a star witness bearing mute testimony to the hopes and fears of an entire culture—rugged individualism gone terribly awry.

When the trial ended in 1998 the cabin was sent to a storage facility in Rancho Cordova, California where it was, in effect, incarcerated, as Richard Barnes observed when he documented the cabin a series of haunting photographs. Barnes explained his pictures of the cabin as an attempt to “bridge the gap between the banal and the extraordinary, the cult of celebrity and the seductiveness of the infamous.”

The same can be said of Constantin and Laurene Boym’s Unabomber Cabin, a 2.5” high cast nickel miniature that debuted in 1998 as part of the desingers’ Buildings of Disaster series. A partially ironic commentary on media saturation, a partially serious commentary on the need to mark and memorialize, the souvenir Unabomber Cabin was available for purchase at better design boutiques for several years. Until recently, it was also available at the online store of Boym Partners. Sometime around the turn of the century, the first agent to enter the cabin during the 1996 FBI raid purchased the miniature cabin as a way of making peace with his connection to it.

The cabin would continue to inspire artists for a number of years. In 2004 Daniel Joseph Martinez debuted “The House America Built,” a full-scale reproduction of the cabin done up in bright colors from Martha Stewart’s Signature line of Sherwin-Williams paints. In 2008, the After Nature exhibition at the New Museum of Contemporary Art featured Robert Kusmirowski’s “Unacabine,” also a full-scale version of the cabin, but this time an exact replica–no designer colors, just faux stains and weathering. I remember seeing After Nature, but had no recollection of Kusmirowski’s piece, probably because Maurizio Cattelan’s life-size headless horse made a bigger impression (i.e. freaked me out more). Thankfully, David Smiley reminded me about the “Unacabine” a few weeks ago.

The cabin also continued to make news. In 2003, title was transferred to Scharlette Holdman, a member of Kaczynski’s defense team, but for reasons that are unclear she did not take possession of it. Around the same time, the cabin was offered to the Smithsonian; the Institution declines, citing the cabin’s size as a significant reason it did not pursue acquisition. This tests credulity: the cabin is much smaller than many objects in the collection of “American’s attic”: the Apollo 11 capsule, the 1401 steam locomotive, the ENIAC Accumulator #2, the Hart House from Ipswich. At any rate, shortly thereafter, the cabin was to be demolished but for reasons that are unclear it was spared and placed in safe storage at SafeStore near Sacramento.

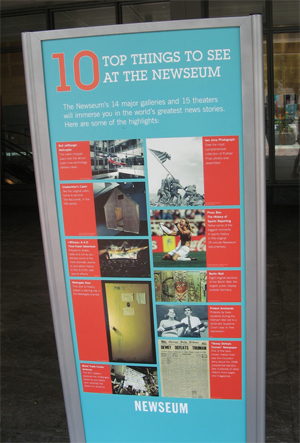

In 2008, it appeared at the Newseum in Washington, DC–decidedly not the Smithsonian, but just a few blocks up Pennsylvania Avenue from FBI Headquarters. Part of a show called “G-Men and Journalists,” the cabin was displayed because, according to one museum official, it was a “definite media hook.” At the very least, it attracted the attention of the Unabomber himself, who protested its display in the museum.

In 2010, John Pistelak Realty of Lincoln, Montana offered the land on which the cabin sat for sale for $69,500, advertising it as a chance to purchase “an infamous piece of U.S. history.” In a striking bit of understatement, the land was described in the listing as “very secluded.” It is not clear if there were any bidders.

Again with the huts 27 March 2011 No Comments

In 1753 a Jesuit priest named Marc-Antoine Laugier writes an essay in which he posits a primitive hut, une cabane rustique, as the origin of architecture. The trunks of four trees growing together in a forest form a rough structural framework; above, their branches grow into a perfect triangular pediment; atop this, their leaves provide an enclosing roof: “et voila, l’homme logé.”

As it turns out, Laugier’s natural hut is not too far off the mark: the trabeated construction of the ancient Greeks did have its origins in simple wood forms that may have been inspired by canopied trees. But Abbé Laugier is less concerned that his primitive hut be understood as an archeological artifact than that his primitive hut be understood as a theoretical idea. At the height of the Enlightenment, this little cabin is utterly polemical, and the man lodging inside it is no less a personage than Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s l’homme sauvage. Just as Rousseau’s noble savage exists happily in a primordial paradise unsullied by the artificiality and corruption of society, so too Laugier’s primitive hut. And in its rustic materiality and unadorned simplicity it embodies a culture of romantic authenticity—the deliberate antithesis of studied, cosmopolitan sophistication.

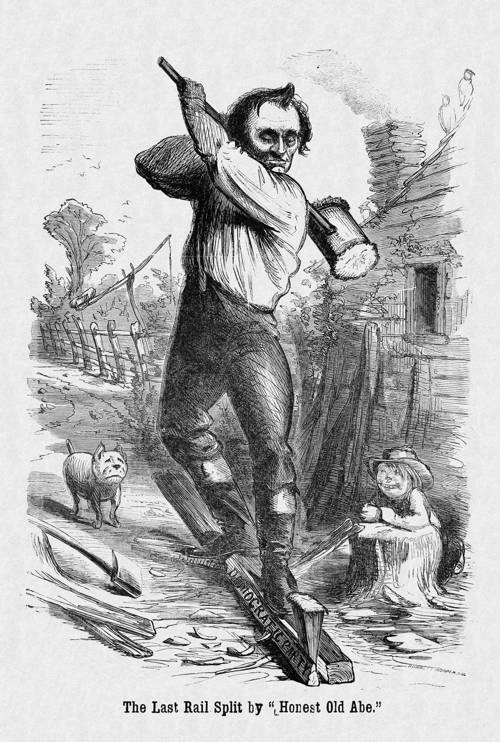

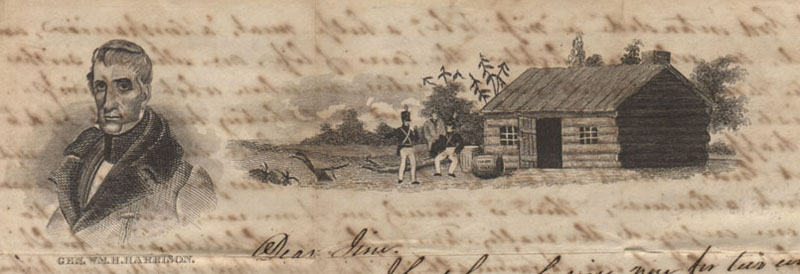

Roughly a century later, the association of simple man and simple cabin becomes fodder for the US political machine during the successful presidential campaigns of William Henry Harrison in 1840 and Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Harrison is a member of the eastern wealthy elite, but this isn’t playing well with the same rowdy electorate that put Andrew Jackson in office.

So, his handlers invent a frontier past for him: log cabin as birthplace, “the house our fathers lived in.” Theirs, not his: from the landed gentry of Virginia, Harrison was born in the big house at Berkeley, a Tidewater plantation.

The jig is up shortly after Harrison’s inauguration: would a true frontiersman have caught a cold and died after only a month in office?

Two decades later, Abraham Lincoln is the real deal: he was born in a log cabin in the backwoods of Kentucky. As befitting these humble origins, he is unaffected and plain-spoken. And during his presidential campaign he is known by the nickname “rail-splitter,” a reference to his chores as a hard-working young frontiersman.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

His log cabin origins are less than a source of pride for Lincoln since they represent the abject poverty that characterized his early life and from which he deliberately escaped. This matters little to the political mythmakers, especially after his assassination in 1865. Though numerous reformers, including Frederic Law Olmsted and Harriet Beecher Stowe, recognize the log cabin for what it is—a primitive hut that is rude and not romantic, the log cabin penetrates deeper into the American psyche.

In 1893 a Lincoln Log Cabin is moved to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. That Abraham Lincoln never actually lived in this cabin is beside the point for the throngs of visitors who touch its rough-hewn exterior as they would the relics of a martyred saint. The cabin was lost after the exposition closed and was reportedly used as firewood.

The CCC rebuilds the cabin in the 1930s on its original site on the Illinois farm where Abe’s father and stepmother moved in the 1830s when the future president was already a lawyer in Springfield. Apparently, there is great interest in historical accuracy, such as it can be gleaned from the photographs that exist, and we can picture the CCC boys resisting their usual tendency towards making things neat and tidy, struggling mightily to recreate the sag of the roof, the irregularity of the chinking, the shagginess of the shakes.

Meanwhile, back at Lincoln’s Kentucky birthplace, his humble hut has become the stuff of legends, enshrined in a classical temple designed in 1910 by a young John Russell Pope channelling von Klenze channelling the Parthenon. Sinking Springs may not be the Danube but the effect is the same, a bluegrass Walhalla for the first memorial ever built to Lincoln.

Inside, is the ur log cabin, supposedly built of the actual logs of the actual structure that witnessed the actual arrival of Abraham Lincoln into this world.

When the cabin is finally reconstructed inside the memorial in 1911, Pope thinks it is too big for the interior and insists that it be reduced in size for easier circulation. American pragmatism trumps cultish sanctity. Pope is right to be unconcerned: in 2003 the National Park Service used dendrochronological analysis to determine conclusively that all of the cabin’s logs post-date Lincoln’s birth by a good four decades. Today, the Park Service refers to the structure without fanfare as “the symbolic cabin.”