It’s a bird, it’s a plane! 27 April 2012 No Comments

When I work at home, I sit at my computer facing west (northwest, to be precise, as the island of Manhattan transgresses the cardinal points), just across the living room from a large window. The view is buildings and more buildings, mainly tenements and towers, plus a sliver or two of the Hudson.

From the 14th floor, these aren’t exactly Rear Window sight lines (though you’d be surprised how many illicit activities take place on rooftops); still, there’s plenty to see. In the foreground, for example, is a very fine water tank, all cedar and tin, that sits on the roof of a mid-rise building on the next block. When Rosenwach rebuilt the tank a few years ago, they topped it off with the decorative finial that is the company’s trademark–four “R”s flanking a thick dowel.

The tank provides an occasional perch for passing raptors. Once, a red-tail hawk fledgling alighted there and proceeded to wail mournfully while it got up the nerve to resume its flight, presumably returning to swankier digs on the east side.

There are water tanks in the background, too, but mainly there’s a non-descript, brick-face high-rise that went up on Broadway in 2005. Despite its looming presence, the tower doesn’t really block the view and there’s ample opportunity to observe the traffic in the west side skies. During the baseball season, the Fuji and Goodyear blimps pass by regularly when the Yankees have a home game. This makes sense because the House that Ruth built is only 3 miles away as the crow flies–and the crow flies here, too.

So do the egrets, gliding by twice a day, moving between the Meadowlands and Central Park, like all the other commuters from Jersey.

After two decades of seeing stuff outside the window, just maybe I’m getting a touch of the blasé attitude that Georg Simmel thought afflicted the mental life of dwellers of the metropolis. When something catches my eye, I don’t immediately reach for my camera; sometimes I don’t even get out of my chair.

This morning was different. Sitting here with a cup of coffee, reading over a manuscript, I heard a distant rumble, louder than a trash truck, deeper than a helicopter. I looked up and glanced out the window: nothing out of the ordinary, but that noise required investigation. I reached the window in time to see a jumbo jet cruise by on a low flight path over the river with a space shuttle riding piggyback.

It was the Enterprise en route to the Intrepid. As you can see in the photo that appeared on the New York Times website a few minutes later, it was way cooler than a blimp.

Looking out the window, grinning like a kid, exclaiming loudly, I was reminded of something I read years ago, when I was working on the New Deal and the Great Depression. In The Politics of Upheaval, volume III of Arthur M. Schlesinger’s The Age of Roosevelt, the eminent historian quotes Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia: “Too often, life in New York is merely an squalid succession of days; whereas in fact it can be a great, living, thrilling adventure.” The Little Flower knew what he was talking about.

The Founding Mother 9 April 2012 No Comments

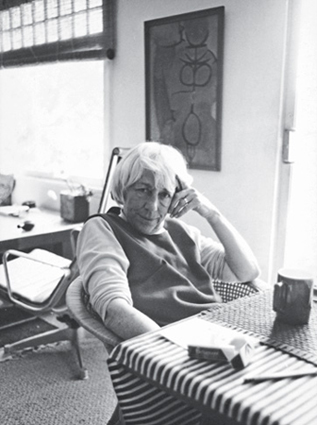

I’ve been reading Esther McCoy lately.

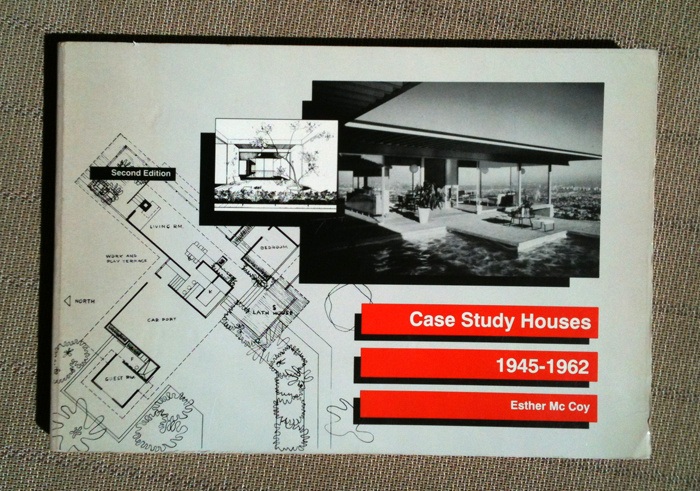

The other day I pulled an old copy of Esther McCoy’s Case Study Houses, 1945-1962 off my shelf and discovered that my second edition of 1977 has a crackling introduction in which McCoy examines the “brave-new-world tone” of her introduction to the first edition of 1962 in light of the architectural realities of the 70s. For McCoy, the decade and a half between the two editions (years that, she notes, saw the completion of Moore et al’s Sea Ranch, Larabee Barnes’ Haystack, and Venturi’s Mother’s House) changed the imagery of the American house as resolutely as the Case Study houses had in their day.

I hadn’t looked at the book in some time, but East of Borneo Books had just sent me a copy of a new volume of McCoy’s collected writings, Piecing Together Los Angeles: An Esther McCoy Reader. Reading the Reader, I was struck by the sly wit and insightful critiques that characterized the essays, short stories, and memoirs it contained.

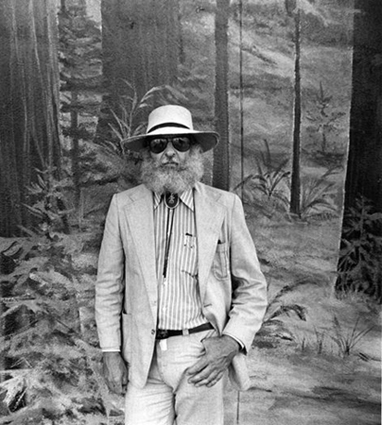

Reyner Banham noticed this about Esther McCoy’s work several decades ago, and the Reader also includes a 1984 tribute he wrote on the occasion of McCoy’s 80th birthday. Calling her “the founding mother,” Banham credited McCoy with doing more than any other individual to raise awareness of California’s rich tradition of, and pioneering contributions to, architecture in the 20th century.

Having shamefully neglected the founding mother, I’ve been going through my shelves to see what other texts I’ve overlooked. My best find to date is McCoy’s contribution to High Styles: Twentieth-Century American Design, the publication that accompanied the 1985 Whitney exhibition of the same name. McCoy’s essay deals with architecture and design in what she calls “the Rationalist period,” 1945-1960, and while it deals with California and the Case Study houses it gives equal consideration to the buildings AND their furnishings.

The essay also places iconic furniture of the period–like the Eames’ storage units and Saarinen’s tulip pedestal line–into their proper socio-cultural context by examining issues like mass-production, ergonomics, and housework. McCoy’s essay, like the rest of High Styles (which includes David Gebhard on traditionalism in the 1920s, Rosemarie Bletter on modernism in the 30s, Martin Filler on interiors and social change in the 60s) is a model of erudition and accessibility.

And, of course, those qualities are apparent throughout the Esther McCoy Reader, not only in essays on major figures (like Schindler and Neutra) and buildings (like the House on Kings Road and the Lovell House) but, surprisingly, in fiction. McCoy’s “The Important House,” published in The New Yorker in 1948, is a spot-on dissection of mid-century design culture, presented as a comedy of manners in which the owners of a modernist house—the important house of the title—cope with the high-style fastidiousness of their architect and his photographer as they stage the interiors for a shoot. Part of what is remarkable–and remarkably funny–about the story is how fresh it is, and how it resonates with early 21st century design culture, regularly in evidence in all its mid-century splendor in the pages of Dwell.

Piecing Together Los Angeles: An Esther McCoy Reader is expertly edited, with super-informative introductions, by Susan Morgan, who also co-curated the MAK Center exhibition “Sympathetic Seeing: Esther McCoy and the Heart of American Modernist Architecture and Design.” That show, the first exhibition to examine the full range of McCoy’s work as an architectural critic, historian, and preservationist, was intended, in Susan’s words, “to affirm McCoy’s unassailable role as a key figure in American modernism.” With the publication of the Reader, that affirmation becomes even more concrete because the book does not just piece together Los Angeles, it also pieces together complex narratives of modernist architecture—its icons and places, its personalities and foibles, its polemics and ambitions—in Southern California, in the United States, and in the 20th century.

A few weeks ago Susan Morgan and I discussed the founding mother’s legacy at Van Alen Books. You can watch the full conversation here.

Biking to Brick City, Part I: Prologue 23 October 2011 No Comments

A few nights ago, I was on my bike at the corner of Houston and Sullivan waiting for the light to change. A mangy guy on the sidewalk was gesticulating in my direction, clearly trying to get my attention. While my normal inclination is to ignore such requests, I was feeling magnanimous: it was a beautiful night and earlier in the evening a friend had been generous with an excellent single malt Irish whiskey. So I turned to see what the guy on the sidewalk had to say.

“You gotta be crazy to ride a bike in New York City,” he yelled at me.

Clearly, this guy has not been paying attention: New York, as most people know, is in the midst of a bicycle renaissance, with nearly 300 miles of new bike lanes built by Janette Sadik-Kahn’s DOT and a bike-share program scheduled to launch next year. And while there is a tendency to think that Manhattan and the gentrified neighborhoods of Brooklyn are the biggest beneficiaries, last weekend’s ride out to JFK to tour the TWA Terminal included a few nice stretches along designated lanes and routes in Queens.

Digression: the bike lane on 157th Avenue took us right past New Park Pizza on Cross Bay Boulevard, which some claim is the best in the borough. It was a pretty good slice, but looking at modernist landmarks always makes me hungry so my judgement might have been impaired.

There’s even a bike rack at the AirTrain station in Howard Beach. And though I doubt I’ll be towing my carry-on wheelie bag any time soon, the “City,” a British-made trailer/suitcase combo just might convince me to trade in my beat up Tumi.

Of course, I didn’t have time to explain any of this to the mangy guy on the sidewalk in the Village before the light changed, so I laughed instead: “Not so crazy,” I told him, “at least, not any more.”

When I first started riding in New York City in the late 80s, in the glory days of the kamikaze bike messenger, you did have to be kind of crazy. If the taxis didn’t get you (and they got me twice), the potholes and the broken glass did. Back then you rode on Park Avenue because there weren’t buses on it.

Never did I imagine a day would come when there wouldn’t be any cars either, even if only for a few Sundays in August.

Because of Summer Streets and its bike-friendly ilk, the mean streets of the five boroughs have begun to fade from view and recede in memory. But those feeling nostalgic for a city less kind and gentle can take heart–there’s a reasonable facsimile a mere 8 miles away as the crow flies, though getting there by bike is a whole lot further.

Riding a bike in Newark in 2011 does feels like riding in New York twenty years ago. I’m not really exaggerating. There’s not as much traffic, but there aren’t any bike lanes (though the first protected bike lane in the entire state is under construction near Branch Brook Park) and motorists seem even more aggressive towards cyclists than they are towards pedestrians–and that’s saying something. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve been nearly run over while crossing with the light in a clearly marked pedestrian walkway–it happens at least once a week. But in Newark, whether on two feet or two wheels, it’s not the taxis you need to worry about, it’s the SUVs, literally the Suburbans from the suburbs, whose drivers are doubly distracted–by their phones and by their outsized anxiety about being in Brick City.

Still, like a good citizen of the region–Greater New York when I’m east of the Hudson and Greater New Jersey (as Dennis Gale put it) when I’m west of it–I persevere.

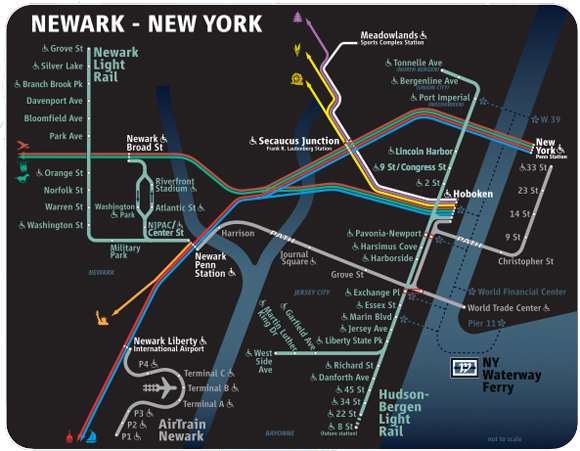

I leave the Mini in Manhattan, take the subway to Penn Station, switch to NJ Transit and arrive in Newark 17 minutes later (21 minutes if we stop in Secaucus). From the Broad Street station it’s a 10 minute walk to school.

Last year I started riding my bike to Newark on days I don’t teach. More specifically, I started riding some of the way to Newark: from the Upper West Side, I pedal south on the Hudson River Greenway to the World Trade Center, take the PATH to Newark, and then ride one mile from downtown to University Heights. This saves no time, though it does save money ($11.50 total), but that’s an added bonus. The point is the seven mile ride on the Greenway.

Though intolerably congested on weekends, during weekday commuting hours (and late at night) the Greenway is a joy. Some may prefer the stretch that passes through Chelsea and the West Village, where the rebuilt piers have the sheen of the luxury city.

I favor the portion that passes under what remains of the West Side Elevated Highway of the 1930s–and not just because when you are under there you don’t have to look at all those ugly towers Donald Trump built on the old New York Central rail yards. What I like about riding the Greenway under the Highway is the layering of past and present and the way the bike lanes, and the whole southern extension of Riverside Park, reclaim the spatial detritus of the automobile. That may sound portentous, but transforming a dismal undercroft into usable public space really does signal a critical change in urban planning strategies over the past few decades. Think of it as “collage city” besting the “noble diagram.”

I favor the portion that passes under what remains of the West Side Elevated Highway of the 1930s–and not just because when you are under there you don’t have to look at all those ugly towers Donald Trump built on the old New York Central rail yards. What I like about riding the Greenway under the Highway is the layering of past and present and the way the bike lanes, and the whole southern extension of Riverside Park, reclaim the spatial detritus of the automobile. That may sound portentous, but transforming a dismal undercroft into usable public space really does signal a critical change in urban planning strategies over the past few decades. Think of it as “collage city” besting the “noble diagram.”

And since I’m being grandiloquent, I’ll admit something else. Since I started riding my bike [some of the way] to Newark, whenever I look west across the Hudson while on two wheels, I think of the Situationists. Now, this could be simply a bad habit I picked up in graduate school; not unlike the heroine in Cathleen Schine’s Rameau’s Niece (“What was the point of having read so much incomprehensible Derrida if one could not make philistine deconstruction puns.”), it displays my self-satisfaction at erudition goofy enough to conjoin radical French urban theory from the 60s with present day New Jersey.

And since I’m being grandiloquent, I’ll admit something else. Since I started riding my bike [some of the way] to Newark, whenever I look west across the Hudson while on two wheels, I think of the Situationists. Now, this could be simply a bad habit I picked up in graduate school; not unlike the heroine in Cathleen Schine’s Rameau’s Niece (“What was the point of having read so much incomprehensible Derrida if one could not make philistine deconstruction puns.”), it displays my self-satisfaction at erudition goofy enough to conjoin radical French urban theory from the 60s with present day New Jersey.

More seriously, it could be that cycling in as congested and auto-loving a place as New Jersey is kind of like a détournement for the age of sustainability, in a beach-beneath-the-streets sort of way. Upon consideration, though, I’ve come to realize that the reason I’d been thinking of the Situationists while looking at New Jersey from the other side of the river is that I’ve been harboring a secret desire to turn biking to Brick City into a dérive.

Coming soon: Biking to Brick City, Part II: “Sire, I am from the other country.”

Drive In Down East 4 September 2011 No Comments

ME State Route 102 is a two-lane highway that stretches like a lazy figure 8 across the western lobe of Mount Desert Island. It was built in the early 1930s as a continuation of the highway that connected Augusta, the state capital, with down east, via Belfast and Ellsworth along the coast. In the late 1930s, that route was designated ME 3 and continued onward to Bar Harbor, the island’s biggest town and the social center of the summer rusticators. 102, by contrast, served the more hard scrabble working towns of the island’s quiet side: Southwest Harbor, Tremont, Bass Harbor.

As such, 102 was never overrun by the tourist honky tonk that typified the state’s major coastal highways, like Route 3 and especially U.S. 1, as it runs from the state line in Kittery all the way to Canada. By the middle of the last century, critics were bemoaning the degraded state of those roadsides. In Harper’s, Bernard deVoto complained that the coastal routes had degraded into a “neon slum” of tawdry amusements and cheap-jack restaurants, of drive-ins and diners.

E.B. White was somewhat kinder in the New Yorker, calling Maine’s highways “a mixed dish” of “Gulf and Shell, bay and gull, neon and sunset, cold comfort and warm, the fussy facade of a motor court right next door to the pure geometry of an early-nineteenth-century clapboard house with barn attached.” For White, however unavoidable “the garish roadside stand” might be, the traveler was always conscious of a “triumphant architecture” just beyond it: an extended, unspoiled landscape of pine trees and granite that managed, along with the occasional deer and fox, to “creep within a few feet of the neon and the court.”

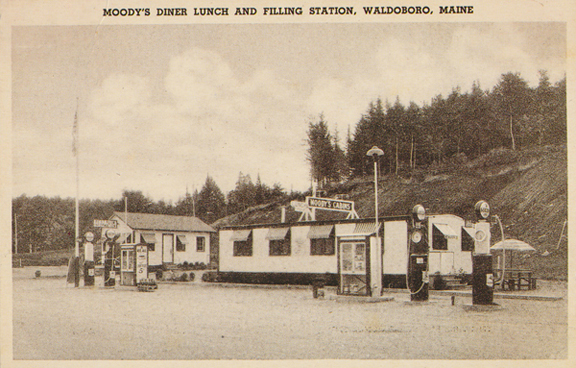

There are only a few places left on Route 1 where you can sense White’s creeping pine trees today, and Moody’s in Waldoboro is one of them. Moody’s opened in 1927 and when White and deVoto were driving the coast, it was the only 24/7 establishment between Portland and Bangor (it closes at 9 pm these days; 10 pm on weekends). But for its iconic neon sign, Moody’s isn’t much to look at: a modest lunch wagon expanded to trailer proportions with two ADA ramps flanking a double-wide entrance.

With living pine trees so close to the building one wonders why it was necessary to decorate the vestibule’s fake shutters with cut-out pine trees. (One also wonders why those fake shutters were necessary in the first place, but that’s a subject for another day.) Perhaps those little pine trees are a talisman against destruction. Widening Route 1 is a persistent threat and for miles up and down the coast big box sprawl has overwhelmed the small-scale roadside stands of an earlier automotive era. This is one reason places like Moody’s are so revered. The quality of the diner’s whoopie pies is another.

Whoopie pies are not on the menu of the Seawall Drive-In one hundred miles north on Route 102, but pine trees and granite are very nearby. And while the place lacks neon, it does have sea-foam green accents on the coping of the modestly canted roof, the bollards separating the parking and picnic areas, and the log fence along the road. In Miami Beach this would barely register as color, but a New Englander might find it a a touch garish. I am not a New Englander (indeed, I was born in Miami, which may explain a few things), so the place charms me.

On a bright summer day, few things are better than a freshly painted CMU box, especially when it’s got a plate glass storefront with aluminum flashing outlining the alternating heights of the display and ordering windows, which have both sliders and louvers.

Frederick Kiesler abstraction it ain’t, but that’s a smiling sort of modernism the Seawall is showing to Route 102–one that would be even more obvious from the road if the proprietor hadn’t blocked the view with split-rail planters and plastic armchairs with faux-caning on the seats and backs.

The drive-in takes its name from a natural barrier of smooth granite rocks that separates the pounding ocean from a tranquil pond just down the road in Acadia National Park. It’s called a natural seawall because humans didn’t actually build the thing, though they had something to do with the asphalt and the yellow lines.

The Drive-In was abandoned for many years but it reopened recently, which I learned while reading maine., purchased at the Whole Foods in Portland before heading up the coast. The magazine is beautifully produced, if a bit too self-conscious–note the miniscule letters and the punctuation in the title. And if its design reflects the long shadow of Martha Stewart Living, it’s got a better sense of humor–note the backside of the camper in the tent pictured on the cover. Plus, you have to appreciate a publication that knows its demographic so clearly (recall where I got my copy): “upscale readers who have a passion for all things Maine.” As long as those things include only the accoutrements of bourgeois privilege, craft beers and weekend getaways, and not, say, the crushing poverty of the inland counties or the deleterious effects of gentrification on the working harbors of the coast.

The Drive-In was abandoned for many years but it reopened recently, which I learned while reading maine., purchased at the Whole Foods in Portland before heading up the coast. The magazine is beautifully produced, if a bit too self-conscious–note the miniscule letters and the punctuation in the title. And if its design reflects the long shadow of Martha Stewart Living, it’s got a better sense of humor–note the backside of the camper in the tent pictured on the cover. Plus, you have to appreciate a publication that knows its demographic so clearly (recall where I got my copy): “upscale readers who have a passion for all things Maine.” As long as those things include only the accoutrements of bourgeois privilege, craft beers and weekend getaways, and not, say, the crushing poverty of the inland counties or the deleterious effects of gentrification on the working harbors of the coast.

At any rate, “engaged and active” reader that I am, I took maine.’s recommendation to check out the under-new-management Seawall Drive-In and drove down the lower loop of Route 102 (officially 102A).

The Seawall still serves the kind of roadside fare you’d expect in these parts (hamburgers, lobster rolls, clam chowder) but with an emphasis on fresh and local and biodegradable plates, forks, and spoons.

I can attest to the quality of the Maine-raised beef. The burger I had on my first visit was quite good, as was the blueberry lemonade. And the pleasantness of the setting, whether at midday or on towards evening, undoubtedly enhances one’s enjoyment of the food.

As for the Seawall’s frozen confections, they needed no enhancing whatsoever, though that 7-mile hike to the summits of Norumbega and Parkman Mountains probably didn’t hurt. The blueberry gelato rivaled any you’d get at Giollitti, and since you’d be unlikely to find wild Maine blueberries anywhere in Rome, this drive-in down east just might have the Eternal City beat.

Historiographic Note on Frozen Confections 12 August 2011 No Comments

The first time I watched the 1972 documentary “Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles” I was too distracted by the “Baede-Kar,” a dash-mounted radio tour guide system with a voice only slightly less creepy than HAL 9000, to pay much attention to frozen confections. But watching it again this morning (yes, it was research), I was delighted to discover that ice cream makes an appearance late in the film.

Banham is pondering what sort of Los Angeles buildings would best represent the city to tourists. Lamenting that L.A.’s best architecture is private and that its public buildings are generally bad, he decides to enlist the help of two local experts: Ed Ruscha and Mike Salisbury.

When Banham reveals that he has invited them to a meeting at Tiny Naylor’s Drive-In and that the meeting will take place in a Cadillac Coupe de Ville convertible, you get the idea that he’s already decided what kind of building best represents L.A.

Douglas Honnold designed Tiny Naylor’s Drive-In in 1949, after he had spent a few years in the office of John Lautner. Julius Shulman’s splendid 1952 photograph of the place makes it clear that Honnold had learned a few things about exuberant commercial modernism from the Googie master because that cantilevered canopy is clearly poised for flight.

Tiny Naylor’s stood on Sunset Boulevard at La Brea until it was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a box so banal I won’t even post a photo of it.

But I digress. As Banham, Ruscha and Salisbury pull in to Tiny Naylor’s they put down the hardtop and have barely come to a stop before the carhop waitress hands them menus. Banham quickly selects a pineapple sundae and tucks into it with gusto once it is served.

I’m not sure what kind of ice cream I thought the eminent architectural historian and all-around design guru would be partial to, but I can tell you that this oddity never crossed my mind. When I was scooping ice cream professionally, nobody ever ordered pineapple sundaes and the syrup sat in its vat slowly congealing. But that was the east coast in the 80s; perhaps the west coast in the 70s was different. I will rely on my Angeleno friends to enlighten me on this issue.

Postscript: both Ruscha and Salisbury had BLTs.