Obama and Jesus 18 March 2009 2 Comments

I’ve just added a new album that I’m sure will grow as the trip continues. You can view it on my Photos page or click the link here:

Walking around D.C. I was struck by the cult-like images of Obama that I saw everywhere. Driving around Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas I was struck by the cult-like images of Jesus that I saw everywhere. John Lennon was excoriated when he declared the Beatles “more popular than Jesus.” I don’t think there’s much of a contest between the President and J.C. Right now, the Lord is clearly in the lead.

Hailing from the place Jon Stewart has called “the land of Jews and Sodomites,” I must admit that I find all these public displays of faith perplexing. In a part of the country where the vast majority of the population is Christian, it seems unnecessary. Of course, I am not so naive about cultural politics as to pretend that I don’t understand why this is happening.

Christ of the Ozarks was built in the mid-1960s atop Magnetic Mountain as a giant advertisement for a local Passion Play. The virginity billboard near Carthage isn’t, technically, a Christian symbol but has a certain inflection. The Twice Born shop in Eureka Springs reminds me of what cynics used to say about the mainstreaming of gay merchandising: “it’s not a movement, it’s a market.”

Missing from the album is a photograph that I didn’t take yesterday. I was about five miles out of Eureka Springs on Highway 62 when I passed a man walking slowly by the side of the road. He looked to be in his mid-60s, with short gray hair and a relatively trim physique. He was wearing jeans and a t-shirt. He was carrying a seven-foot wood cross on his shoulder. He had a small knapsack tethered to the base of the cross which was bumping across the ground as he walked. He smiled and waved as I passed.

I drove a bit further and then was moved to turn around. I pulled up along side and asked the penitent how far he was going. He told me he hoped to make it to Eureka Springs that day. He seemed chipper despite his obvious exertions. I asked if he was carrying the cross for Lent. He said no, that he would carry it everyday if he had the chance. I should have given him a bottle of water as the day was getting warm. Instead, as a truck pulled up behind me and honked, I drove off. When I turned back around and passed him for the final time he waved at me even more vigorously.

A Late Breakfast in the Ozarks 17 March 2009 4 Comments

The combined food wisdom of Jane and Michael Stern and John Edge is unlikely to steer one in the wrong direction. So it was with confidence that I decided to make a 25 mile detour from Eureka Springs in search of a hearty breakfast at the War Eagle Mill in Rogers. It wasn’t really even out of the way, though I ended driving those same 25 miles back to Eureka Springs because Thorncrown Chapel wasn’t open before I left.

______________________

Highways 23 and 127 dropped down from the hills of the Ozarks into rolling farm land and War Eagle Road took me deep into protected lands. War Eagle Mill is the third one to occupy the site; it was built in the early 1970s on the foundations of the previous two. Supposedly, this three-story red clapboard structure recreates the approximate appearance of the original c. 1830.

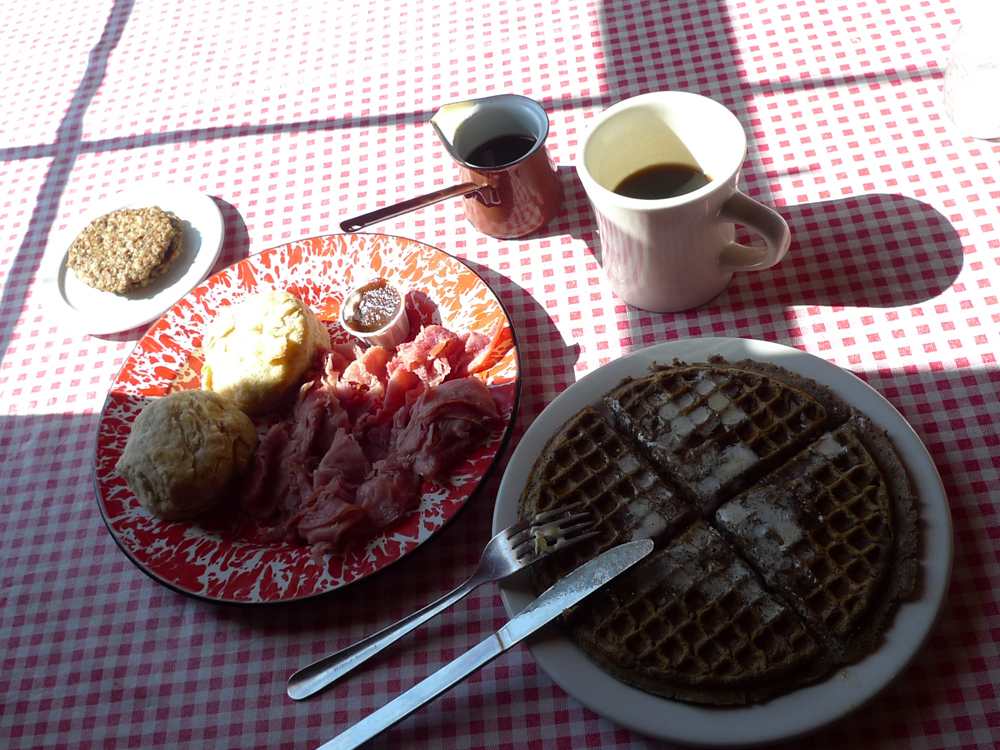

The unfortunately named Bean Palace Restaurant occupies the top floor. It’s a wide open room with picnic-like tables covered in plastic red checked table clothes. You order at the counter from a straight forward breakfast and lunch menu featuring the mill’s products and other local ingredients. I ordered Breakfast #3, buckwheat waffles with sausage patties, but in the interest of sufficient sampling also added sides of biscuits and shaved ham.

I ordered coffee too but it is not worth mentioning except to note that it was served in diner-style mugs of the classic Buffalo China variety. They were old and well-used but not chipped or stained and had precisely the right heft. As for the white liquid offered to lighten the coffee, well, it still perplexes: a non-dairy creamer called “Irish Creme.” I asked for something that came out of a cow but was told they had no milk.

At any rate, my breakfast was brought to my table by a gentlemanly server who looked to be about 70. He was wearing a trucker’s cap and had a very long white beard. He appeared amused at the amount of food I ordered but was too polite to mention it.

My buckwheat waffle was delicious and put to shame the very tasty buckwheat pancakes I had yesterday at the Pancake Pantry, a beloved Nashville institution. This waffle was crunchy on the outside and full of a dark nutty flavor. It was substantial but still light and with just a touch of maple syrup provided the perfect foil for the sausage patties. They were very thin with just a bit of spice and I didn’t need to be told that they were made from local pork.

Oh noble pig! I sing your praises twice this breakfast. The shaved country cured ham was a mound of near perfection. Slightly sweet with just the right note of saltiness and thin enough to pass for a sort of rustic prosciutto. It was excellent by itself but very nice when accompanied by a biscuit. These were made from a hearty white flour (maybe a sort of light whole wheat?) with a nice crust and perfectly fluffy in the middle. My order of two came with a small paper cup of locally made apple butter to spread.

I wolfed down one biscuit and half the ham (having already consumed my waffle and sausage patties) and carefully made a sandwich with the rest. I would surely need it later in the day to power me through my time in Bentonville, home of all things Wal-Mart.

View from the Road 16 March 2009 1 Comment

I’ve just posted two new albums of photographs: License Plates and Public Toilets. You can find them on the Photos page or follow these links. I’ll update them regularly.

My intention was to maintain Ruscha-like neutrality, but I couldn’t help adding captions which, by their nature, are unavoidably subjective. And since I’ve just admited that I had Ruscha in mind, then there is no point posturing about objectivity. I think it is problematic to be both self-conscious and objective. At the end of the day, I like the Prius-driving Queer Christians for Obama too much to pretend I don’t.

As for the toilets, given the prominence that public restrooms assume during a cross-country road trip, it seemed necessary to document these. I will resist rating them on a sanitary scale and content myself with other matters. I’m wondering if certain patterns will emerge with respect to scale, materials, and style.

To date, I can report that the faux historicism of the restrooms in the new U.S. Capitol Visitors Center matches perfectly the faux historicism of the rest of the CVC. Designed, it seems, by the Office of the Architect of the Capitol, the restrooms are a tepid version of the ones found in the New York Public Library and many other Beaux-Arts institional buildings. The ventilation may be better in the CVC stalls, but everything else is worse. Down on the mall, the clean modernism of SOM’s renovation of the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History is found in the restrooms as well: stainless steel, terrazzo, tiles, and silestone for the sink counters and some very nifty benches.

Garden State Ramble, part II 12 March 2009 2 Comments

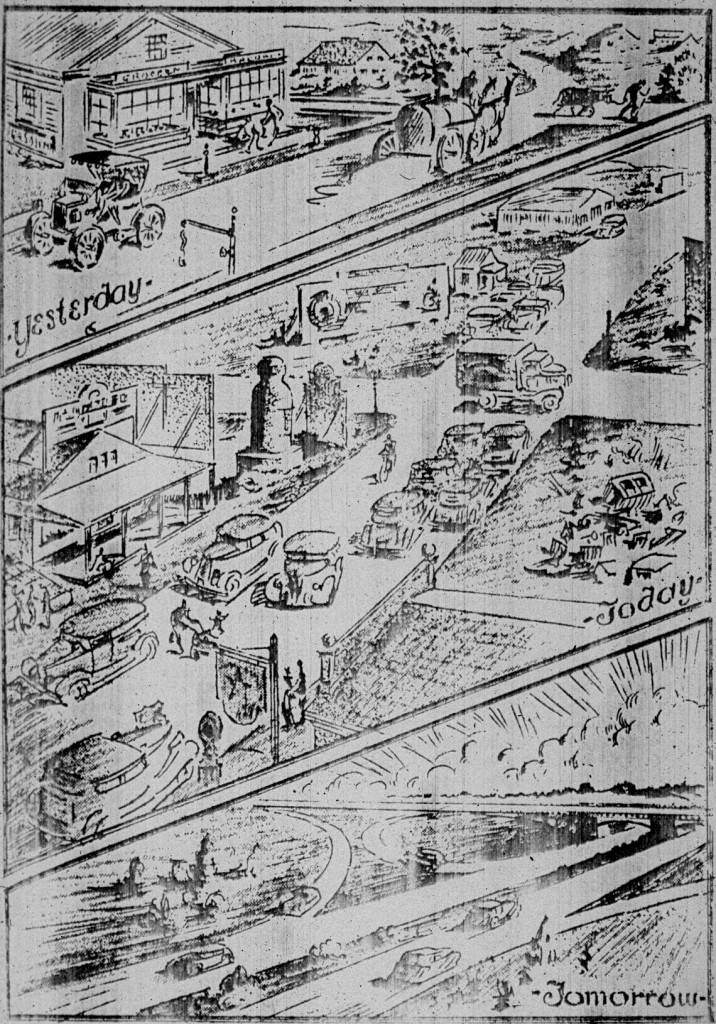

When driving long distances, whether on the interstate or a country highway, any number of things will make the experience more pleasant: a well-placed cup holder, a working gas gauge, a decent radio station, clear directions, good weather, etc. But of all the things that shape the driving experience, as drivers, we rarely give much thought to one of the most important: the efficient highway junction.

The basic morphology of junctions is pretty straightforward. At grade roads intersect with each other at the surface level (either at 90 degrees or in a roundabout). Traversing an intersection in the face of opposing at grade traffic requires good will and faith even when signage and signals are present. In grade separations, one road remains on the surface and the other is raised to a different height level. This improves traffic flow and speed by allowing opposing traffic streams to cross without contact. The problem with simple grade separation is the lack of access to the intersecting road.

Enter the interchange, which combines the traffic flow advantages of grade separation with the convenience of at grade entrance and egress.

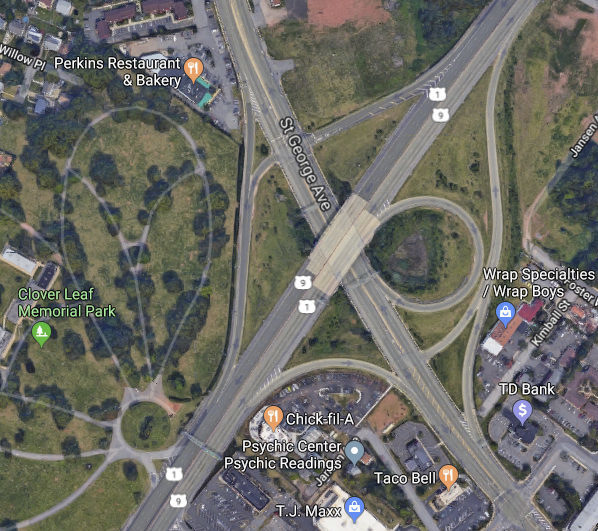

The other day we got in the car and drove off in search of the origins of the interchange, traversing far too many at grade junctions while leaving Manhattan. Our destination was the town of Woodbridge, better known as Exit 11 on the New Jersey Turnpike. Settled in the 17th century, Woodbridge was home to a thriving brick industry well into the 20th century. Lots of towns in Middlesex County can boast about their bricks, only Woodbridge has the world’s first “safety engineered superhighway intersection” and that’s where we were headed.

.

.

.

.

.

.

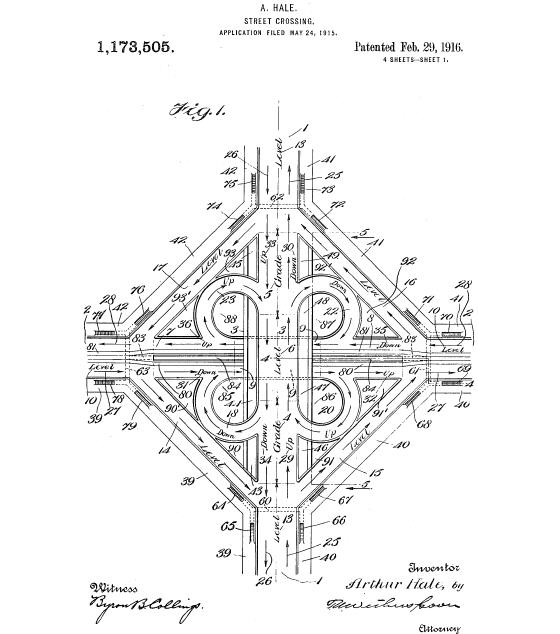

In 1916 a Maryland engineer named Arthur Hale patented a “street crossing” design in the shape of a cloverleaf. In essence it was a grade separation augmented by four circular loops that allowed drivers to connect to the overpass and underpass in both directions, on both roads. This is pretty close to what got built at Woodbridge, for the first time ever, in 1929.

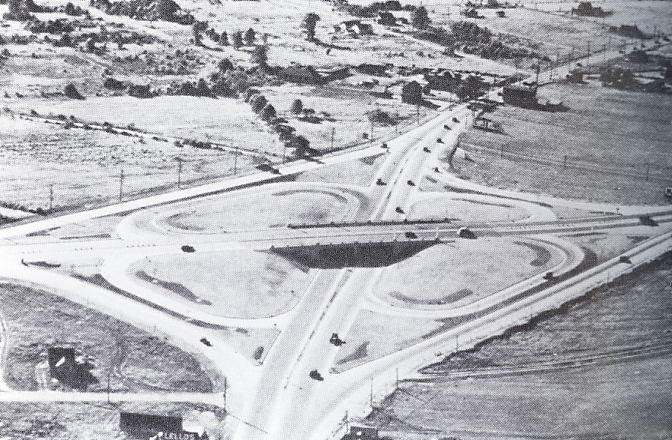

Designed by Edward Delano of the Philadelphia contracting firm of Delano & Rudolph, the Woodbridge Cloverleaf connected two of the most important highways in pre-turnpike New Jersey: Route 25 (now U.S. 1 & 9) from Jersey City to Camden, and Route 4 (now N.J. 35) from New York City to the Jersey Shore. Though these may look like quiet country highways in period photographs, they weren’t. By the late 1920s traffic in New Jersey was already considerably more congested than elsewhere in the U.S. and these roads were major thru-routes between New York and Philadelphia. Today, they carry more local traffic than they did eighty years ago but they remain as congested as ever because of the rapid development of Woodbridge and the surrounding townships.

Driving south on the 1 & 9 from Jersey City we passed several drive-thru car washes with long lines of people waiting, I can only assume, to wash their cars. This seemed like a mystery: I’ve been known to wait on extremely long lines for pizza and even hotdogs, but a car wash? Clearly, this was an essential part of car culture that I had somehow overlooked. In the interest of thorough field work, I added “car wash” to my list of things to do on the road trip.

Having passed on the car wash opportunity, we continued into Woodbridge and were on top of the cloverleaf before we knew it. No worries–without even braking, an easy left exit, a gradual downgrade, and a smooth turn in the vicinity of 270º took us from the 1 & 9 down to route 35. We swung under the overpass and pulled off the road to have a look.

If your map is a few years old, or if your mapping software hasn’t updated its data, what you see when you look at this historic junction is a cloverleaf. Alas, the reality on the ground is somewhat different: an “improvement” project in 2004 enlarged two of the petals. While this may have eased congestion, it distorted the simple, balanced elegance of the original form.

This distortion of a significant landmark in the history of the American highway makes the Cloverleaf Cemetery across the street all the more poignant, marking the site where “our national flower,” as Lewis Mumford disparagingly called the concrete cloverleaf, first took root.

A final note: the same NJDOT project also destroyed the charm of the the 1937 bridge that spanned the 1 & 9 at the cloverleaf. Designed by engineer S.A. Snook and architect A.I. Lichtenberg of the NJ Department of Transportation, it was a single span steel bridge with concrete piers and balusters. Like George Dunkelberger’s bridges on Merritt Parkway in Connecticut, the bridge at the cloverleaf had detailing and styling (art deco in tile and cast aluminum) that was taken for granted in an era when the aesthetics of infrastructure were understood to be just as important as function. The ARRA-funded shovel ready projects of 2009 would do well to bear this in mind.

Preamble Ramble around the Garden State 28 February 2009 2 Comments

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

On a sunny, cold Saturday at the end of January we got in the car and headed from the Upper West Side to New Jersey. It’s a short trip, about 5 miles, but it always seems momentous. Maybe it’s the drama of the Hudson as it narrows between Fort Washington and Fort Lee. Or maybe it’s the drama of O.H. Ammann’s George Washington Bridge, whose towers are so high and mighty (at 604 feet) they made Le Corbusier nearly giddy when he saw them in 1935. In the bridge, Corb wrote, “steel architecture seems to laugh.” And even today, if you drive across the upper deck or look at it from a distance on those rare nights when the towers are fully illuminated, it’s easy to understand why he called it “the only seat of grace in the disordered city.”

The sublimity of cables and beams aside, the momentousness of the journey must also have something to do with crossing a state line. Anyone who grew up in Middle America surely remembers the ritual of the state line–honking the car horn, holding your breath, etc. These rituals probably stem from the significance of state jurisdictional boundaries, especially as depicted in popular culture.

The rangers had a homecoming in Harlem late last night; and the Magic Rat drove his sleek machine over the Jersey state line.

Those are the first lines of Bruce Springsteen’s Jungleland, the final, nearly operatic track on his 1975 LP Born to Run. It hardly needs mentioning that the only way to drive any machine from Harlem to Jersey is to cross the Hudson on the GWB (we will grant the Boss artistic license for stretching the boundary of Harlem about a mile north). Thirty plus years later, notwithstanding the expansion of the megalopolis, regional scale, and tri-state areas, the state line still means something. And this is probably why, for me, driving to New Jersey remains a bigger deal than driving to Brooklyn, even though I’ve been working in the Garden State since 2001 (of course, I don’t drive to work and that probably figures in here somehow, too).

Our destination that morning was the New Jersey Palisades, the sheer stone cliffs that rise from the west bank of the Hudson River. They are imposing things, the Palisades, 550-feet tall with a natural grandeur that holds its own against the man-made mountains across the river. They’re so big that during WWII someone proposed building a bomb-proof shelter inside them; Hugh Ferris even did renderings of the wacky scheme–part Piranesi, part Boullée, with fighter jets thrown in for good measure. Our plan was to hike along the top of the cliffs to enjoy expansive views of the river and the Manhattan skyline.

We started in the parking lot at the Ft. Lee Historic Park. Just west of where we parked the car, the Continental Army had attempted, in vain, to prevent the British from taking control of the Hudson in 1776. Just west of where we parked the car, our hardy band attempted, in vain, to locate the trailhead for the Long Path in 2009. The posted maps were strangely inscrutable, as were the blazes. They all seemed to indicate that the trail left the park, followed a busy feeder road for the bridge, and then proceeded up the GWB’s north walkway, closed to pedestrian traffic since 9/11.

Though this made little sense we reluctantly gave it a try and soon found ourselves climbing the steep steel stairs that lead to the bridge walkway. A locked gate prevented us from accessing the walkway itself, but there was a small deck leading to another set of stairs, and then to what was clearly a marked hiking trail–one foot on the bridge and another foot in the woods. It was a happy threshold and I noted it to myself as a transitional moment. I didn’t realize it would be the keynote for the day.

As we walked through the woods following the trail north, I kept waiting for the traffic noise to grow fainter; it didn’t. But we hiked on contentedly because the sun was shining and the snow was crunching underfoot and because we kept thinking the trail would change just beyond the next big tree. After about a mile, the trail did change: it revealed the backside of a gas station. Despite the unlovely vista it presented from the woods, some of our party availed themselves of the facilities. I, meanwhile, grappled with the dawning realization that we were spending our idyllic escape-from-the-city morning smack in the middle of a highway right-of-way.

The gas station we’d stumbled on was a service plaza of the Palisades Interstate Parkway. It was built in the late 1940s when just about anything with a planted median could get away with calling itself a parkway, but this one really was a road through a park. In the late 19th century local (wealthy) landowners concerned about the devastation of the Palisades from quarrying and timbering (trees cut on top of the cliffs were tossed down the side for transport on the river) formed a park commission. By the 1930s both the Regional Plan Association and John D. Rockefeller supported the idea of a cliff-top roadway running through a continuous recreational preserve.

It was Rockefeller who donated the land we were hiking through that morning. The problem was that his 700 acres gift, though 13 miles in length was less than half mile in width. So up on top of the cliffs, even with a wooded buffer, the parkway remains a sort of keening presence. But this just might be appropriate for hiking in New Jersey, the state with the country’s densest population.

After awhile the din of the traffic made me smile and I thought of Benton MacKaye, father of the Appalachian Trail. MacKaye was a dedicated conservationist but he was also a pragmatist who wanted to balance nature and civilization. He would have understood the nexus of footpath and parkway as inevitable and necessary. A bit further north, that nexus became even more pronounced.

As the trail pulled west it came right alongside the roadway, so close that we were now hiking the parkway and I was tempted to stick out my thumb. The blazes were no longer painted on trees but on the tops of sawed-off sign posts. This may not have been the “deep dramatic appeal” that MacKaye envisioned for the modern hiker, but it had some kind of perverse appeal nonetheless. This may have been simply the appeal of the spectacle we presented as we walked with a dog along a highway. After about a third of a mile the novelty wore off. At the next junction we turned away from the parkway and followed a road down the side of the cliff to the river’s edge.

The Shore Path has pleasures of its own: little sand beaches, stone stairs into the water, and, of course, dynamite views of Manhattan. On this morning, however, the footing was bad, alternating between ice and mud and we had to abandon it. Instead, we walked south along the river road. Known officially as Henry Hudson Drive, this is an old style road that was built for pleasure driving beginning in 1916. Under the bridge and out of the park, we were on back on Hudson Terrace, the feeder road where we picked up the Long Path trailhead. We walked up the hill to the top of the cliff where we left the car. The sidewalk, extra-wide and newly built, felt like the last link in the funky trail system we’d been exploring. Not quite urban, not quite rustic, but the perfect footpath for a day of hiking in Jersey.