Cruising to a Stop on the Pacific Coast 31 March 2009 2 Comments

I was delighted with my first glimpse of the Pacific Ocean and pulled over at the first opportunity to scrambled down to the beach and test the water. My jubilation was not to last.

A run of nearly 6,000 miles without a speeding ticket came to a halt last night in Gold Beach, Oregon.

________________________

Way back in Texas a fellow road tripper warned me against in-town speed zones and I had been conscious of them across six states. In most towns there is a sort of stepping down of the speed limit: from highway speed to outskirts speed, to downtown speed. Not so in Gold Beach where it went from 55 mph to 30 mph at the town line. Before I had even realized that I was actually in a town, since the only thing I had passed was a Motel 6, I was caught on radar going 60 in the 30 zone. I realized too late that I was going too fast and perhaps if I had slammed on my brakes for the yellow light I might have been OK.

The officer was very polite as he made me wait in my car for 30 minutes and then handed me a summons with a base penalty of $432. He assured me that I was getting off easy since he hadn’t written me up for careless driving.

My options: return to Gold Beach for a hearing on April 22nd; plead guilty and pay the fine; plead not guilty and request a different date for a hearing; plead no contest and write a letter explaining that I wasn’t familiar with the local laws. A judge will decide how much I have to pay. The officer strongly recommended this option.

I will take his advice. But it’s going to take me a lot longer to get to San Francisco today.

Wal-Mart Skyline, part II: In the Belly of the Beast 28 March 2009 2 Comments

On reason I journeyed to Bentonville was to visit an old friend who used to live in New York but who came to this small town in northwestern Arkansas a few years back.

Since college, I’ve had great affection for Asher Durand’s Kindred Spirits (1849). An important painting of the Hudson River School and a central document of 19th century American culture, it depicts the artist Thomas Cole and the poet and journalist William Cullen Bryant standing in the vast wilderness of the Catskills. For many years the painting hung without fanfare in a corner of the Edna Barnes Solomon Room of the New York Public Library. I visited it frequently when I was in graduate school since it was close to my regular study spot in the main reading room.

When the NYPL revealed that it had quietly sold the painting in 2005 people were upset. When the NYPL revealed that it had quietly sold the painting to Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton for Crystal Bridges, her new museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, people were apoplectic. Henry James would have appreciated the spectacle, and the irony, of the east coast establishment expressing outrage that their cultural patrimony was being plundered by a nouveau riche upstart from somewhere west of the Hudson (in fact, Walton had been a serious collector for a number of years). What goes around comes around.

Moshe Safdie is designing the new museum, which is supposed to open in 2010. The published drawings show a series of light-filled structures set in a wooded landscape with prominent water features. One of the renderings depicts Kindred Spirits installed in a white box gallery. When the painting hung in the NYPL, the majesty of the landscape and the sumptuousness of Carrère and Hastings Beaux-Arts interior balanced each other nicely. It remains to be seen if Safdie’s white box will enhance or diminish the power of the painting.

The day I visited Bentonville the museum’s temporary digs were closed, so my attempts to see Kindred Spirits again were thwarted. I subsequently discovered that the painting isn’t even in Bentonville right now. It’s on temporary loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I drove 1200 miles to see a painting that is hanging a 20 minute walk from my apartment. Go figure.

I had another reason for visiting Bentonville. I wanted to see where it all began. I wanted to stand before the humble origins of the largest private employer on the planet. I wanted to gaze upon the umbilicus mondi of the company whose annual sales are greater than the GDP of three quarters of the world’s economies. I wanted to visit Sam Walton’s original 5 & 10 on Main Street.

This store opened in 1950 with a double frontage, a central location, and nothing whatsoever to indicate that it would spawn a retail giant with the power to control the manufacturing and distribution of consumer goods across the globe.

[The first Wal-Mart, built in nearby Rogers in 1962, no longer exists. It was on a highway outside of town and contained 16,000 square feet of retail space–about five times as much as the Bentonville Walton’s, but diminutive when compared to the company’s contemporary big box behemoths, containing an excess of 100,000 square feet.]

Today, the original Walton’s houses the Wal-Mart Visitor’s Center. Wal-Mart caps, t-shirts, license plate holders, and Walton’s autobiography are for sale (cash only!) in a front room that retains its original red and green checkered linoleum floor.

Back rooms chart the history of the company, combining facts and figures with corporate ephemera and inspirational quotes by the founder himself. While a few charts document Wal-Mart’s growth in the U.S., an entire room is devoted to its global expansion. Here, world domination has an awfully friendly face. (But not a smiley face. A year ago, the company lost its efforts to claim the familiar yellow smiley face as a Wal-Mart trademark.)

That friendly expansion is tracked on old fashioned tote boards up front. On the day I visited there were 3503 Wal-Marts, 602 Sam’s Clubs, and 150 Neighborhood Markets in the U.S. Internationally, there were 3498 Wal-Marts and 131 Sam’s Clubs. This was over a week ago; there are probably more by now.

Also on display are a few of Walton’s personal possessions: his Ford pick-up truck, a bronze head of his prized English Setter, and his office as it looked on the day he died in 1992, complete with cheap wood paneling, drop ceiling and 70s furniture.

I admit to not really feeling the aura of the GREAT MAN as I studied these items. For the record, this isn’t because I am immune to feeling auras: the reconstruction of Thomas Jefferson’s library at the Library of Congress (Day 1) bristled with the founding father’s enlightenment intellect and Donald Judd’s live/work spaces in Marfa (Day 9) thrummed with the minimalist’s artful OCD.

The only vibe I got from gazing at the Walton artifacts felt like corporate P.R. trying to convince me that to his last days “Mr. Sam” was was a down home small town merchant. This may be true, but he was a small town merchant whose most lasting legacy was a profound contribution to the decline of the American small town.

Except in Bentonville. Though it is surrounded by Wal-Mart sprawl in every direction–Associate Stores, Supercenters, Layout Centers, Distribution Centers, and Lifestyle Centers–Bentonville’s actual center exuded prosperous vitality when I was there. Main Street and the town square are in immaculate condition and the whole district is a Wi-Fi hot spot.

I bought an iced latte at a café on the square (not a Starbucks) and sat down in the warm Arkansas sun across the street from the original Walton’s. I thought of the countless Wal-Marts I’d passed on my journey from New York to Bentonville and of all the depressed small towns I’d driven through. And as I sat there looking at the Walton’s, Victor Hugo suddenly came to mind: “ceci tuera cela.” This will kill that.

Wal-Mart Skyline, part I 26 March 2009 No Comments

Though the rapid growth of Las Vegas in the past two decades has transformed the surrounding desert, roughly 50 miles north of the city all that development gives way to a lot of empty land. It looks that way on the road atlas map and the reality on the highway doesn’t change one’s impression.

The towns along Highway 93–Alamo, Ash Spring, Caliente, Pony Springs, Steptoe, Wells–are little more than crossroads. Commercial development is limited to a few gas stations with convenience stores, a few saloons, and, of course, a few casinos. Supposedly, Ely has the only supermarket for 250 miles. From what I saw it was little more than an oversized bodega.

After driving 500 miles through the open range and mountain passes of eastern Nevada, sometimes going an hour without passing another car, it was something of a shock to cross the state line into Idaho and have the sudden, unmistakable, sense of settlement. Just beyond the border the mountains give way to broad valleys filled with cultivated fields and closely spaced towns.

As I drove on, the shock of settlement turned into resignation as I waited for that inevitable moment that would signal definitively the return to civilization.

It occurred a few miles west of Twin Falls whose half shuttered Main Avenue stores were long ago made obsolete by the strip malls of Highway 93. And as 93 draws near to the interstate, the retail scale bumps up again as the strip malls give way to the big boxes. And of all the big boxes, the biggest one is Wal-Mart.

The Wal-Mart Super-Center of Jerome, Idaho is located at 2680 South Lincoln Avenue. It is close enough to I-84 to be visible from the highway. Not visible from the highway is Jerome’s Main Street, two miles north and in another world in retail terms. I didn’t drive into Jerome to see how its Main Street was faring. I didn’t need to. The precise location of the Wal-Mart Supercenter rendered that short journey completely unnecessary.

___________________

Wal-Mart is not responsible for killing Jerome’s downtown. It is, instead, the most obvious manifestation of a gradual, half-century shift in retail patterns to which nearly every person in this country has contributed. Jerome’s situation is nearly identical to the situation of tens of thousands of other small towns across the country. (And I’ve got the photographs to prove it.)

There is one notable exception. A town does exist that is surrounded by Wal-Marts but has a thriving commercial center. That town is Bentonville, Arkansas.

Next:

Wal-Mart Skyline, part II: In the Belly of the Beast.

Two Days in Nevada 25 March 2009 1 Comment

_____________________

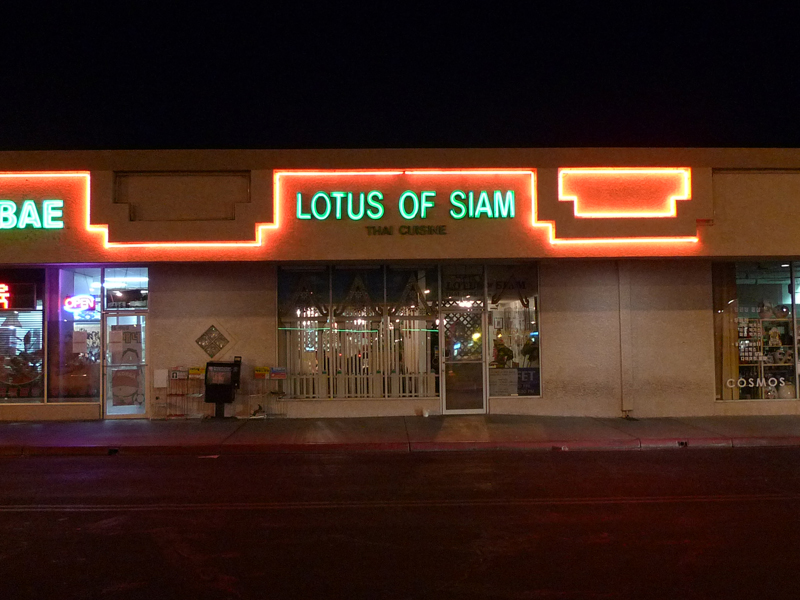

We arrived in Las Vegas on Monday night and headed straight to the Village Square Commercial Center on East Sahara Avenue.

Though most would describe it as a strip mall (and a dumpy one at that), the Village Square is, in fact, nearly a square with four retail arms almost enclosing an enormous parking lot at the center. These arms are one story strips and though some have attenuated roof lines the only thing that distinguishes the Village Square in typological terms is that, in a nod to Sin City contextualism, it features rather more neon than one might expect.

In cultural terms, the Village Square is also typical of a phenomenon directly related to late 20th century immigration patterns. Like so many other dumpy strip malls across the country, it houses an exceptional Asian restaurant. (Alexandria, Virginia is where I first observed this trend back in the 80s.) In this case, the restaurant is the Lotus of Siam, an establishment that both Gourmet and the New York Times have hailed as serving the best Thai food in the land.

I had the Nam Kao Tod, described on the menu as “crispy rice mixed with minced sour sausage, green onion, fresh chili, ginger and peanuts.” It had all this plus two critical ingredients not mentioned: copious quantities of fresh coriander and mint leaves. These gave the dish a bursting tonic quality that was truly stimulating, functioning just like an aperitif.

For a main dish I had Crispy Catfish Pieces Salad, described as “deep fried minced catfish, fresh chili, lime juice, peanut, cashew nut, vegetables, served on a bed of sliced cabbage.” Again, there were a few extra items that were key (though perhaps they are covered by “vegetables”: julienned ginger, sliced celery, and scallions all imparted that same tonic effect (an oversized piece of fresh chili imparted something else entirely when I ingested it accidentally) but here it was mellowed by the presence of the catfish, which was dredged in flour, fried to a golden color, and cut into very thin slices.

Washed down with a cold Singha beer, this was the perfect finale to a long day on the road from Tucson.

Of course, this being Vegas, the night was still young. We left the Village Center and headed to the Strip.

The traffic was heavy with fellow cruisers but the sidewalks were also jammed with the pedestrians who have become commonplace in the past decade.

We turned around at the Strip’s traditional southern terminus (in fact, Las Vegas Boulevard continues on for several more miles): the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign on a traffic island near the original gates to McCarren Field.

Betty Willis designed the sign in the mid-1950s (YESCO built it) and when it was installed on the boulevard in 1959, it was way outside of town. Today, as the casinos and hotels have continued their southward migration away from Fremont Street and downtown, the sign has been very nearly swallowed up by commercial development.

The last time I visited the “Welcome,” I had to pull my car onto the shoulder and dash through heavy traffic to get to the narrow median.

In the fall of 2008 Clark County redesigned the area around the sign, widening the traffic strip to include a small parking lot, palm trees, and amoeba-shaped Astroturf lawns. Roberto Burle Marx meets Morris Lapidus at the edge of landscape urbanism.

We had a room at the Paris. There’s no point in dwelling on the absurdities of the place or in getting all hot and bothered about its bastardization of everything from Le Vau’s Versailles to Garnier’s Opera to Lenôtre’s patisserie (I don’t know what that was I ate for breakfast but it sure as hell was not a pain au chocolat and I’ll only mention in passing the guy who asked for a packet of ketchup for his quiche lorraine).

For me, it’s not the ersatz that’s problematic but the cheapness. And this is where Steve Wynn actually gets it right at the Bellagio (with Jon Jerde as his designer) and the Wynn: the interiors are ridiculous but they aren’t shoddy.

At any rate, the point of staying at a hotel on the Strip is not to contemplate the awful lobby but to enjoy the view from the room. And this one did not disappoint: overtopping the Opera-thingy and full on the Eiffel-thingy with the Bellagio Fountains just across the way.

Seen from 30 stories above the Strip the fountains are more shamelessly Busby Berkeley than they appear from street level: they swing, they sway, they twirl, like a bunch of soft-focus chorines. And since the double pane windows muffled the Celine soundtrack, watching them made me positively giddy.

Fast forward to the end of day 2 which found me driving roughly 300 miles due north on Highway 93, a scenic route for much of the way.

My original destination was Elko because the town has three Basque restaurants and, being the great granddaughter of Juan Esperda of Vizcaya, I wanted to do a little ethnic heritage food tourism. But I was too tired and it was too late (for reasons having to do with the CCC and Michael Heizer which I will relate at another time). So I stopped in Ely instead.

I found a room at the “historic” Hotel Nevada in this former copper-mining boomtown. Built in 1929 with a steel and concrete frame and topping out at six stories, the hotel used to be the tallest building in the state. It still seems like the tallest one around or appeared to be when I first saw the lights of Ely at dusk. Along with my $38 room I got a coupon for a free beer at the Liberty House Saloon across the street. I drank a Michelob Amber Boch and chatted with Dennis, a grizzled race car driver who showed me pictures of his car, “the Black Bitch,” on his cell phone.

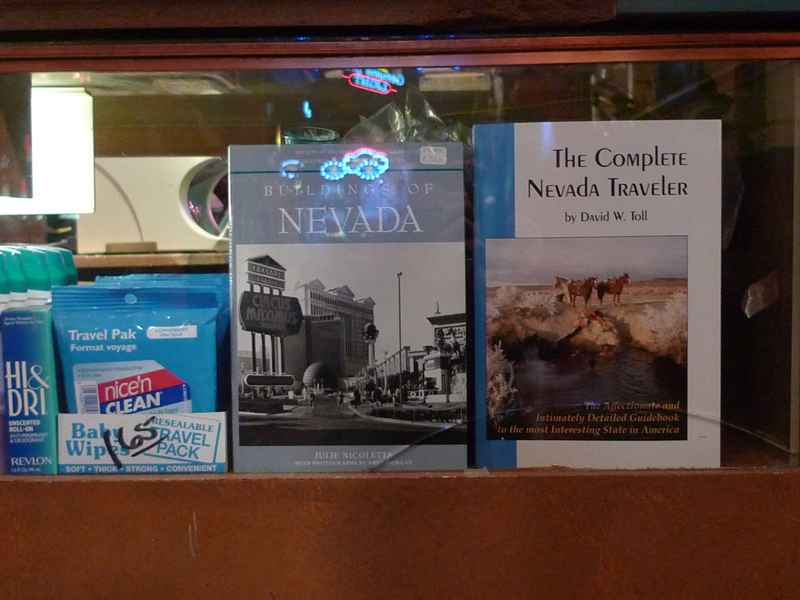

I finished my beer and returned to the Hotel Nevada. While waiting for the elevator I contemplated the array of products in the display case at the registration desk. It was a typical wayfarer’s assortment: shaving cream, pain reliever, toothpaste, deodorant, and the Nevada volume of SAH’s Buildings of the United States (Oxford University Press, 2000).

I bought a copy and went to bed, feeling like I was in familiar territory after all.

A Note on Technology 24 March 2009 No Comments

I’ve been thinking a great deal about Horatio Jackson Nelson, who drove a two-cylinder 20 horsepower Winton touring sedan from San Francisco to New York from in the summer of 1903. His two-month odyssey (May 23rd to July 26th) is generally regarded as the first cross-country road trip. Horatio’s Drive was an impressive feat, but he spent much of his time waiting around for his driving companion, a bike racer and mechanic named Sewall Crocker, to fix the Winton. (His other driving companion, a bull terrier named Bud, just took up space.) Horatio also spent much of his time driving, lost, through, trackless countryside.

106 years later my road trip is a lot easier. For starters, I’m driving a four-cylinder 172 horsepower Mini Cooper S Clubman. My gas tank is only marginally bigger than Horatio’s, holding 13 gallons to his 12, but my gas mileage his considerably better. I get over 400 miles out of a tank; Horatio got less than 200. Of course, my mileage would be much better if I drove more slowly, but then my top speed is 139 m.p.h. whereas Horatio couldn’t get much higher than 30.

Unlike Horatio’s, my car is equipped with a windshield that has proven quite handy for keeping kamikaze bugs at a safe distance as they hurl towards me, sadly ending their days splattered across the glass, and the radiator grille, and the rearview mirrors. This was more of a problem in the swamplands of the South though somewhere in Arizona a beautiful Monarch met an unfortunate end on my car’s front end.

The only bad thing about the windshield is that it removes my only legitimate reason for wearing driving goggles and Bud looked quite fetching in his.

While I don’t have my own mechanic, I have a handy directory of every Mini dealer in the country, plus roadside assistance should I breakdown. And, of course, I have a phone for calling roadside assistance, or the police in case of emergency, or to make hotel reservations, or to tell a friend I’m going to be late arriving because I detoured for fried catfish.

And because that phone is GPS enabled with internet access, I have detailed road maps and driving directions and addresses and miscellaneous useful information for nearly every possible destination at my fingertips. What time is the last tour of the day at Shadows on the Teche in New Iberia, Louisiana? (It’s 4:30.) What’s the name of the famous BBQ joint in Luling, Texas? (It’s City Market.) What’s the meaning of the Texas highway designation F.M.? (It’s farm to market.) How late can we drive through the Saguaro National Park in Tucson, Arizona? (Until sunset.) It’s all at my fingertips.

The fact that I have road maps indicates yet another advantage I have over Horatio. Outside of cities and towns, he had to rely on railway right-of-ways, and there was still plenty of country without even the railroad. By contrast, I’ve got roads, and lots of them, perhaps too many.

In the past week, I’ve driven over 4,000 miles on local roads, interstates, scenic parkways, secondary highways, by-passes, and through-routes. It seems as if there is a road to suit every purpose and mood, from pleasure driving at 30 m.p.h. to flat out cruising at 90+ m.p.h. What with all this infrastructure and equipment my road trip is much more a gentle adventure than Horatio’s wild ride.

Of course, there is such a thing as too much information. Looking at my road atlas after I crossed into Arkansas last week, I determined that I could get across the northern part of the state on a single road, Highway 412. I had to take Highway 412 about 300 miles, turn onto Highway 62 and that was it. This seemed easy: the line of the road was meandering but it went from my point A (the state line) very nearly to my point B (Eureka Springs) without much confusion.

_________________________

Just to be on the safe side, I punched points A and B into the iPhone’s mapping app and it produced a set of ridiculously complicated directions. There were over a dozen different directions just to follow the same line that I drew with my finger in the atlas. The difference was in the specificity since the app tells you every time a road changes names. State highways that pass through small towns change names a lot. To the thru-route driver these name changes are of little consequence. To the mapping software these name changes are critical data points, mile markers on information superhighway.

I turned off the screen and drove on, not exactly off the grid but at least off the GPS.