Mall Walking, part I 22 April 2009 No Comments

___________

Driving from San Francisco to Los Angeles not long ago I headed inland and stopped off in Fresno. The state’s fifth largest city had not been on my list of must-see places, but Paul Groth at Berkeley had assured me it was worth the detour in order to walk the Fulton Mall.

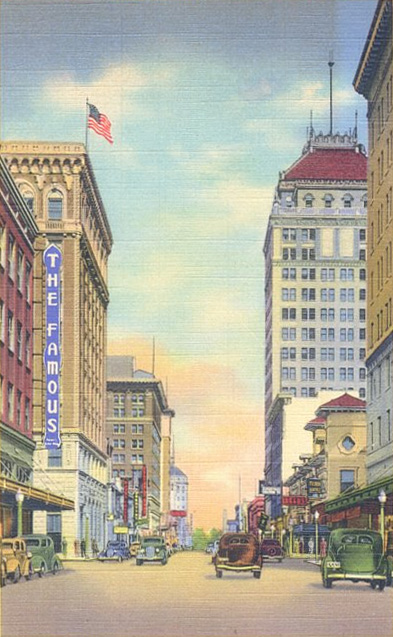

Fulton Street was once the heart of downtown Fresno, lined with its tallest buildings and its largest shops. As in so many other U.S. cities, by the 1960s Fresno’s commercial life had shifted from the center to the periphery. In 1964 city leaders hoping to reverse this trend (and capture their share of federal urban renewal dollars) turned to Victor Gruen to prepare a master plan for Fulton Street’s redevelopment.

Though best known as the inventor of the suburban shopping mall, Gruen made a significant contribution to post-war urban design by promoting the idea that U.S. cities could balance the reality of the street and the dream of the sidewalk. The result was “pedestrian modern,” as David Smiley has smartly called it, a practice of remaking downtowns through superblock planning that acknowledged the necessity of the automobile while embracing the ideal of the walker.

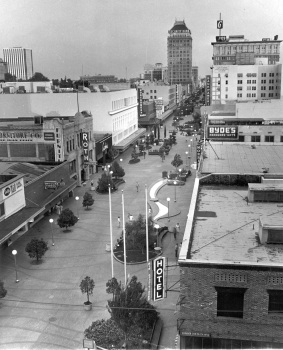

In Fresno, Gruen’s master plan called for the elimination of car traffic on six square blocks of Fulton Street in the central business district and the transformation of those streets into a landscaped pedestrian corridor. He also specified the regularization and modernization of Fulton’s storefronts to create a unified streetscape and the construction of garages to absorb the displaced on street parking.

Garrett Eckbo was responsible for implementing Gruen’s scheme, and the design he produced encompasses an imaginative variety of berms and beds, pavilions and benches, and fountains and pools. These features, mostly rendered in concrete with organic forms, are set into a paved field accented with meandering rubble work and smooth tiles. As a whole, Eckbo’s design has the easy abstraction you would expect from the father of modern landscape architecture and the artful informality you would want for an urban strolling destination.

And strolling is exactly what you want to do when you arrive at the Fulton Mall, especially if it is a hot, arid day in the San Joaquin Valley. I entered the mall in the late morning, crossing Van Ness on Merced Street and passing one of the mall’s original parking garages (Alastair Simpson, 1964). This is a low slung building whose scale and location indicates discretion rather than concession to the automobile.

As soon as you turn into the mall proper you sense the coolness provided by mature vegetation. After forty-four years the ample reach of olive trees and the dense canopy of wisteria make the mall’s benches and pavilions exceptionally pleasant places. They make you want to stop strolling and start sitting.

And quite a few of Fresno’s pensioners and youth were taking their ease on the mall the day I was there. I can’t show you how they looked in situ because they scurried away when they realized I had a camera pointed in their direction. The younger men in baggy jeans and do-rags seemed especially desirous of getting out of the frame.

They weren’t the only ones suspicious of my camera. While admiring the modernized ground floor of the Guaranty Building–all goldenrod paneling and groovy lettering–I was surrounded by several burly men whose anxiety increased the more I ignored them. They kept asking me how I was doing. I responded happily that I was just fine and continued my observations. Apparently, this was not satisfactory. They phoned a superior: “There’s someone here walking around taking pictures.”

Several other burly men showed up wanting to know what I was doing. This seemed obvious but I thought it prudent to explain: “I’m walking around taking pictures.” Their eyes narrowed with suspicion: “Of what?” they demanded. “The Fulton Mall,” I responded cheerfully. Before they could reply I launched into a lecture about pedestrianization and modernism. Their eyes glazed over with boredom.

As they shuffled away, one of them mumbled that they should tear the whole thing down to prevent the homeless from sleeping on the benches; another mumbled that I shouldn’t be allowed to take photos of a government building. It turns out that the Guaranty’s main tenant is the US Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Their exit made it easier for me to sit and admire the fountains and the sculpture adorning them. Many of these works were created by local artists in conjunction with Eckbo’s office. They were paid for privately by Fulton Street merchants and other Fresno business people who were convinced that a program of public art would make the Fulton Mall a true civic amenity. Most of the work is unsurprising late modern abstraction cast in bronze, a friendly hybrid of Brancusi, Noguchi, and Moore. While most of the work looks smashing in the setting Eckbo provided for it, there is only so much pedestalled bronze I can take.

Stan Bitters’ ceramic fountains, at four different sites on the mall, were a welcome change. Apparently, they are meant to evoke the irrigation pipes that made Fresno an agricultural center but they have a Mediterranean whimsy that, in addition to reminding me of the work of Roger Capron, was sufficiently far removed from the metallic geometry scattered about the mall.

The same can be said of Joyce Aiken’s and Jean Ray Laury’s mosaic benches. In the entirety of the Fulton Mall their panels of bursting color fields and syncopated rhythms are matched only by the wild graffiti of the former Gottshalks Department Store.

Though Gottshalks only recently filed for bankruptcy, the Fresno-based chain abandoned its Fulton location two decades ago. Now the prominent building, dating to 1914 and flamboyantly modernized in 1948, is occupied by what is essentially a swap meet. And while the graffiti matches the exuberance of the building, its presence is a reminder of Fresno’s decline.

For the historian, that decline has obvious benefits: the Fulton Mall is almost miraculously intact and frozen in time–which is why the Downtown Fresno Coalition thinks it is a good candidate for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (it was nominated in 2008 but is still under review). But however pleasant the Fulton Mall may be for admiring modernist urban planning, it’s not much good for shopping these days. Many storefronts are empty; many are occupied by cut rate retailers serving a struggling clientele; still others are occupied by social service agencies catering to the same clientele. Restaurants offering cheap lunches for employees of the nearby courthouse and county offices seem to be doing better, but just barely.

Fresno built the Fulton Mall to forestall decline, but the city didn’t realize it was fighting the tide of history. Now there are plans to rip out the mall and reintroduce traffic to Fulton Street. The city is still fighting the tide of history. Design, alas, rarely fixes economics–it didn’t work in 1964 and it’s not likely to work now.

Coming Soon: Mall Walking, part II: from Burbank to Glendale

Taking Things Seriously 15 April 2009 No Comments

A friend gave me a book with this title for Christmas; a collection of short essays about miscellaneous, yet meaningful objects, it’s one part Roland Barthes and one part Antiques Roadshow. Passing through a whole country worth of significant stuff, and with plenty of rumination time behind the wheel, I have been taking things pretty seriously these days. I’ve also been trying to avoid accumulating anything worth taking seriously.

Driving around with a few dozen books, miscellaneous electronics, and footwear for situations both professional and recreational, I’m hardly traveling light. Still, I like the idea of being mythically unencumbered in a Kerouac-boxcar-king-of-the-road sort of way.

This is why on my trip so far, I’ve mainly acquired things that are consumable (Tennessee whiskey, Texas strawberries, Arizona apple cider, California grapefruit) or ephemeral (tourist pamphlets, souvenir postcards–my favorite is from San Xavier del Bac with a die cut Latin cross).

Though I was sorely tempted by an array of aqua colored kitchen items at a junk shop in the Antelope Valley, I opted to leave the display intact for other roadside voyeurs to enjoy.

Sometimes, however, the desire for material possession is so acute that resistance is futile and one has no choice but to give in. Across 19 states and 7700 miles, this has happened to me exactly twice.

______________________

In New Orleans, Louisiana I acquired a hollow concrete block. In Glendale, California I acquired a pink plastic bunny. The block and the bunny have nothing much in common beyond mass-production and me, but by virtue of my acquisition their fates are now intertwined.

Block

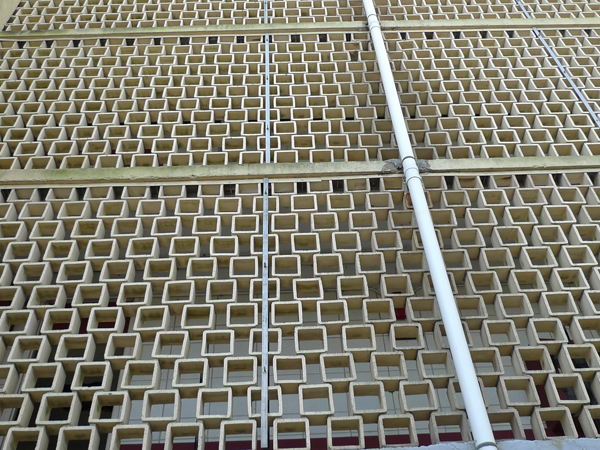

I first spotted the concrete block in situ. We were driving along Highway 61 in Mid-City when a building that could credibly be mistaken for mid-career Corbusier came into view.

Back in the day, it had clearly been a hotel and a swanky one at that. (Thanks to Karen Kingsley, I now know that it was the Pan-American Motor Hotel designed by Curtis & Davis in 1958.) We pulled to the back to have a closer look and were astonished to find monumental free-standing stair towers and a six-story concrete block sunscreen facing open-air galleries.

The blocks were tinted yellow to set them off from the building’s exposed concrete frame and, I suppose, signal their decorative function. Laid in staggered courses with minimal mortar they seem to float when viewed from the ground. Though fifty years of hurricanes had rendered the courses a bit jiggy, this animated the individual blocks and the whole screen seemed to twitch and pulse with mid-century optimism.

The building is being converted to senior housing and the foreman at the site invited us to take a look around. He also told us that Katrina had so weakened the sunscreen that it was being removed and the galleries would be enclosed. I pictured the dull infill façade that would take its place. I thought about the artificial climate control that would trump the original, stylish responsiveness to New Orlean’s subtropical climate–even in our era of supposed sustainability.

I felt a mournful sort of sadness wash over me, and it only increased as I looked around to see that piles of blocks were already littering the site, waiting to be sent to some distant landfill. It was like going to the ASPCA and feeling all those needy puppies tugging at my heartstrings. I decided to take one with me.

Then I decided not to: it seemed silly to carry off a ten pound CMU and then cart it around the country. My companions, however, insisted that I follow my original impulse and Julie marched off to make a selection. She returned triumphant and handed it over. Up close I could appreciate the rounded corners that made it friendly, the rough texture that captured the light, and the true heft that made it the building block it literally was. I basked in the phenomenology of the thing, and then realized how dirty it was making my hands.

Walking back to the car to put it in the trunk, I enthusiastically mentioned how great it would look on the extruded aluminum bookshelves in my Manhattan apartment. Julie quietly suggested that it would look even better on the Ikea bookshelves in my Newark office. She may assist me in procuring an obscure object of desire, but that doesn’t mean she wants to live with it.

In the meantime, the block is back outside, where it belongs. From a temporary perch on a terrace in Los Feliz it happily frames cypress and eucalyptus trees and a spectacular view of downtown L.A.

Bunny

Walking through an open-air shopping plaza off Brand Boulevard in Glendale on the day before Easter, I spotted the bunny in the seasonal window display of a store that was straining hard at a kind of packaged pseudo-cool. At first I didn’t realize it was actually for sale; it seemed impossible that I could own a thing of such perfect compact oddness, but there was another bunny on the half-priced table. Not only could I buy this bunny, I could buy it at a fifty percent discount.

The bunny is 18 inches tall and stands alert, yet relaxed with one paw hanging limply and the other pulled close to his torso. His pose is as close an approximation of a contrapposto as a bunny could be expected to manage. I won’t go so far as to say that the bunny resembles the David, but there is a quiet dignity about the way he gazes knowingly into the distance, ears cocked in anticipation of something out there on the horizon. It’s probably not Goliath, but the bunny still seems brave.

The bunny is made of hard plastic, but he is covered in hot pink flocking that gives him a certain resemblance to both the Velveteen Rabbit and a basement rec room from c. 1970. Around his neck is a white ribbon that is dapper, but superfluous. Across his back is a dense patch of sparkles that suggest the far away roller disco glamour of a more innocent time.

If Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami opened a factory in China, this bunny would be the result (without the ribbon). But that’s what makes the bunny so compelling. A factory in China made the bunny without any help from international art world superstars. My host in L.A. suggested we find the factory and start selling the bunny at Moss. I liked the idea of hundreds of 18 inch pink bunnies in those lofty white interiors. I also liked the idea of a solitary 18 inch pink bunny boldly resisting the detritus of my everyday life.

Neither block nor bunny is what Thoreau called “necessary of life,” but I am compelled to give this account of them lest they be mistaken for the “accumulated dross” that Henry David so vigorously condemned during his life in the woods. The concrete block cost me nothing. The plastic bunny cost me $6.49 plus tax. Given how good they look together, with their contrasting colors, textures, and forms, I’d say this was was a bargain.

A Latte in the Mission 9 April 2009 No Comments

A damp morning in San Francisco requires a good strong cup of coffee but I had concerns. When I was in Portland I had several lousy lattes. I have no doubt there is fine espresso to be had there, given the caffeine proclivities of the Pacific Northwest, and I am sure that I simply made poor choices. But when you have tasted bitter grounds, as it were, you need to be cautious.

Initially, my host recommended the place around the corner from his apartment in the Castro. Then he paused and looked off into the distance for a moment, the way one does when remembering something pleasant. If you find yourself around 14th and Valencia, he began, there’s a place called Four Barrel.

I didn’t find myself here, I walked deliberately here. What’s a 20 minute detour for good coffee, especially if it’s sort of on the way to Thom Mayne’s Federal Building?

I caught the aroma of the place from across Valencia-a good sign, as was the self-concious lack of signage and the bare wood and concrete styling of the place. Not a potted plant in sight, only a hand-built fixed gear leaning artfully against a rough hewn copper paneled counter. Only later did I notice the four boar’s head hunting trophies hanging above the pre-packed beans.

The barrista’s tattoos were beautifully layered floral patterns, neither Celtic nor Asian, they were entirely original. I hoped the coffee he made would have the same attention to detail.

He placed a heavy saucer on the counter and chatted amiably with the confidence of a true craftman as he made the espresso and steamed the milk. I imagined him as an historic re-enactor explaining to some future tourist how urban Americans lived at the start of the 21st century.

When he put the cup, now one quarter filled with a dark loamy liquid, on the counter I came back to the present tense. He paused in a deliberate way, letting the milk settle. Then he poured it into the cup with a flourish. His pouring achieved one of those milk/coffee patterns. It was lovely in a skilled but understated way. It looked like one of his tattoos.

I carried it with two hands to my table so as not to disturb the foam. Then I went back for my donut. A light yeasty thing, orange scented with a thin vanilla glaze, it was delicious; the perfect foil for the main event.

As the coffee pushed through the milk at my first sip it had the perfect flash of acidity that mellowed into a chocolatey kind of depth of flavor as it mixed with the creamy foam.

Neil Young was playing on the sound system–from vinyl, not mp3. By the time “Helpless” was over my cup was empty. The coffee was just like the music: comforting, satisfying, well-crafted, and damned good.

Auto-Pilot without Cruise Control 7 April 2009 4 Comments

Driving in Los Angeles is like walking in New York. It is utterly unavoidable and constantly shifting between extremes of exhilaration and annoyance. Automotive congestion, like pedestrian congestion, has its own internal rhythms, ebbs and flows, and these can change subtly and suddenly, requiring a Zen-like mastery of each new traffic situation whether on the sidewalks of 42nd Street or the egress lanes of the Hollywood Freeway. Mobility, regardless of its native form, must derive its essential character from urbanism as a way of life.

This might explain why driving in Los Angeles is so different from driving in New York. Cars are not indigenous to the five boroughs, despite Robert Moses’ attempts to prove otherwise. That’s not the case in L.A. As Reyner Banham observed nearly forty years ago, “like earlier generations of English intellectuals who learned Italian in order to read Dante in the original, I learned to drive to read Los Angeles in the original.”

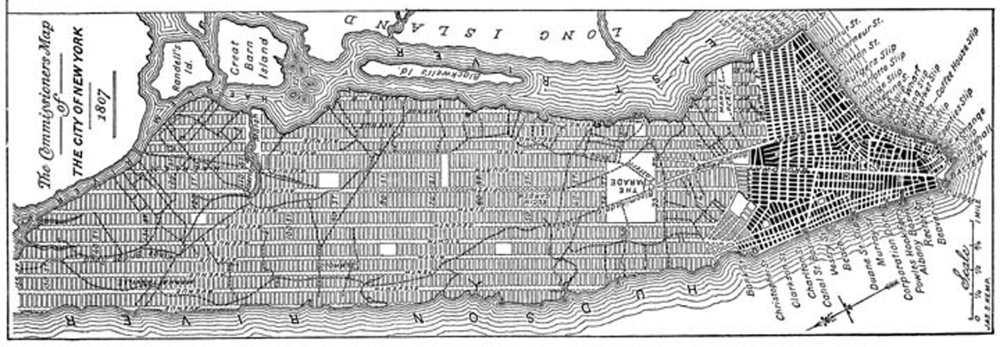

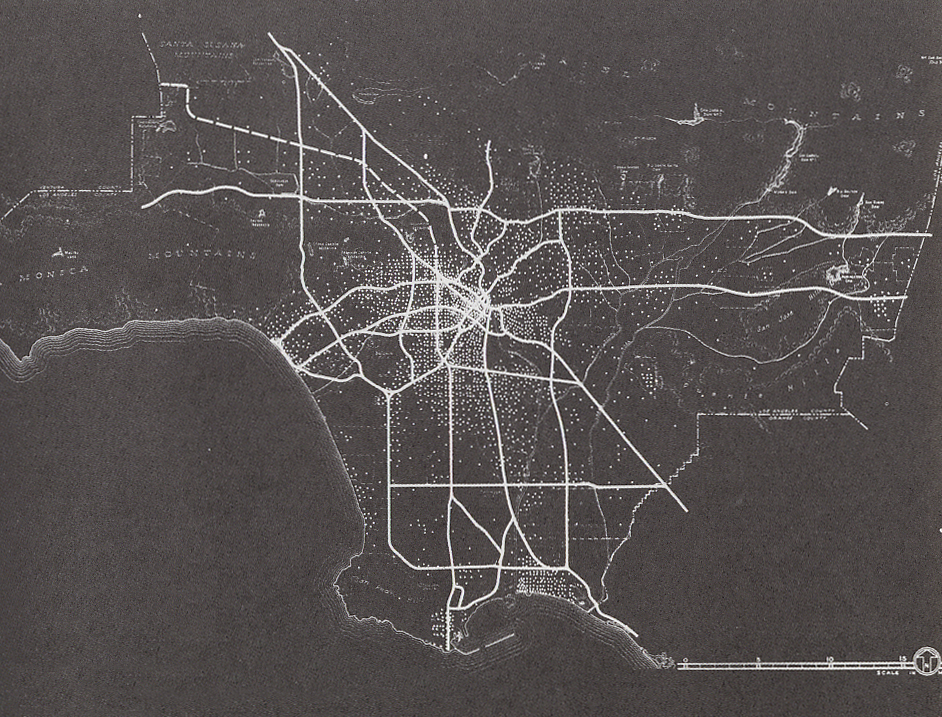

Compare the ur-circulation documents for each city and the distinction is clear.

The Commissioner’s Plan for New York (1807-11) laid out a horse and buggy street grid on the 23 square miles of Manhattan island. The Freeway Plan for Los Angeles (1940-43) laid out an automotive highway network on the 4,000 square miles of Los Angeles County.

The difference is even more obvious when you are behind the wheel in L.A. and the freeway opens wides on the other side of your windshield: as many as six lanes in either direction, dedicated streams of entrance and egress, and spacious junctions and interchanges whose straightforward utility masks their enormous complexity.

Though my evidence is admittedly anecdotal (after only a week on L.A.’s roads), it seems as if the local driving style follows the lead of freeway design. If driving in New York is about jockeying for position, driving in L.A. is about forward momentum. If driving in New York is spasmodic and competitive, driving in L.A. is smooth and confident. Maybe it’s cruise control that produces the steadiness of the driving here; or maybe the steadiness of the driving allows the use of cruise control. I can’t test either hypothesis because my car doesn’t have the right equipment.

Still, as I’ve been motoring across the county, from surface road to freeway, from the 5 to the 10 to the 405 to the 101 to the 134 (note the use of the definite article, a local custom), there have been moments when the driving becomes strangely familiar. It was positively uncanny the other day, when I drove to Los Feliz on the 110.

The right-of-way and the roadbed shrank. The curves got tighter and the lanes got narrower. Even the overpasses were shorter, plunging each car into momentary darkness. Exits came up fast and disappeared just as quickly. Cars cut each other off to avoid entering traffic. All around me it felt like laid-back, one handed driving was giving way to intense focus with two hands gripping the wheel tightly.

______________________

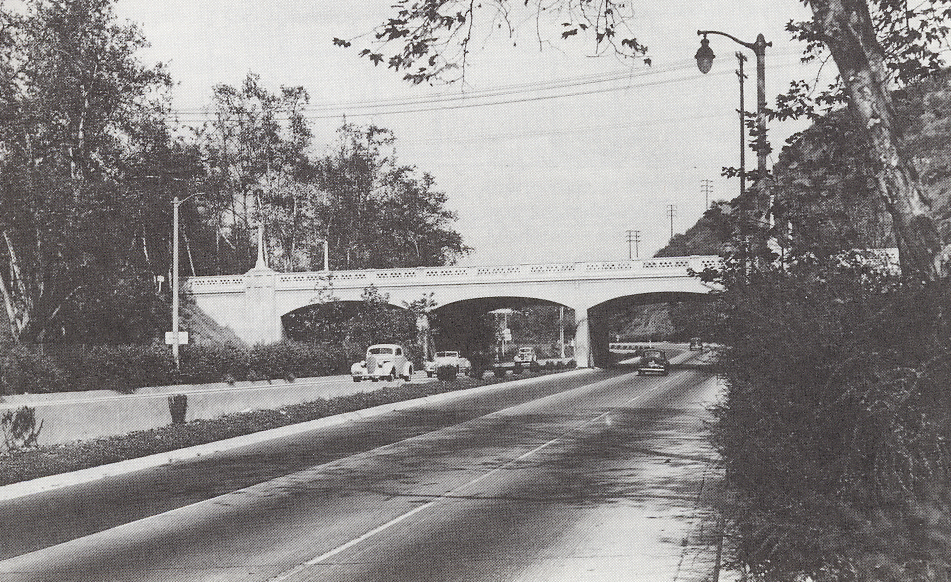

I knew this was the Pasadena Freeway, but it felt more like the Bronx River Parkway. It felt, in other words, like an old road. Not old the way El Camino Real is an old road (the Camino runs along part of US-101 as it passes through the city and has a special highway designation), but old for a high-speed motorway, and certainly old for Los Angeles.

The earliest, northernmost sections of the Pasadena Freeway were built in the late 1930s as the Arroyo Seco Parkway. The first grade-separated, limited-access, divided-highway in the urban west (according to HAER), the Arroyo Seco laid the foundation for what would become L.A.’s iconic freeway system after WWII.

Like Connecticut’s Merritt Parkway, its exact contemporary, the Arroyo Seco was a hybrid: half scenic motorway intended for pleasure driving along the old gorge and half high-speed corridor intended for commuting between downtown and the northeastern communities. But by the time the full length of the road was completed in the 1950s, the original six mile stretch of the Arroyo Seco was subsumed into the county’s ever expanding freeway network.

Today, though vestiges of the parkway are evident in the lushness of the landscape and the detailing of the bridges, most drivers probably register the road’s uniqueness more intuitively or subconsciously as a kind of auto-body-driving-reflex. At any rate, I registered it that way. Forget the 12-lane freeway; here was a road I knew how to drive. I threw the Clubman into sixth and took the next curve without braking. And then I casually took one hand off the steering wheel.

Why I Like Abstraction 4 April 2009 2 Comments

Standing in front of Michael Graves’ Portland Public Service Building in a steady rain it was hard to imagine that this dingy postmodern box had caused so much fuss back in 1980. Today, the controversy has faded as surely as the building’s colored tile veneer. What remains startling 30 years later is not the cartoon classicism, but the monumental sculpture above the entrance on the building’s west side at 1120 SW Fifth Avenue.

This 36-foot tall figure is Raymond Kaskey’s Portlandia, an embodiment of commerce who first appeared on Portland’s city seal in the 1870s. As a heraldic emblem, she possesses a certain naïve charm: pioneer ambition mixed with local boosterism to produce a pseudo-mythic figure who conjured history and tradition for a city that was barely two decades old. As a colossal statue, she is nearly grotesque: squatting on a dinky pedestal and lurching forward in an almost threatening manner, she is more urban panhandler than civic symbol.

Though Graves’ histrionic backdrop was partially to blame, something else was influencing my intensely negative response to Kaskey’s work: I couldn’t help but compare it another monumental sculpture, one I had seen a few days earlier, one whose monumentality made Portlandia seem like a lawn ornament.

______________________________

A thousand miles before and a world away from downtown Portland, I drove to the top of Mormon Mesa outside of Overton, Nevada in search of Michael Heizer’s Double Negative of 1969. Though I had detailed directions, courtesy Nick Tarasen’s website, I wasn’t sure the Clubman was up to the journey. Tarasen recommends a four-wheel drive vehicle with high clearance; I had neither, but figured that if the road got too bad I would simply turn back and if I damaged the car in the process, I’d have plenty of daylight to walk back to town.

On the top of the mesa, the unpaved main road deteriorated into little more than a dusty gravel path; sometimes it was just bare rock. The scrubby mesa top was criss-crossed in every direction by ATV desire lines that made it difficult to follow a specific route. After a few miles I parked the car, as directed, and walked to the mesa’s eastern edge hoping Double Negative would come into view. It didn’t. I crouched down and peered over the side. All I saw was the mesa’s gently eroding face giving way to the Moapa Valley and the Virgin River below.

I continued walking north, stopping every few feet to take a good look at the east face, making sure that I wasn’t missing something significant. After 30 minutes of gamely searching, while I was enjoying the view, disappointment started to temper my enthusiasm. Nonetheless, I walked on, following the mesa edge as it jogged decidedly west.

Something in the distance caught my eye. It was almost imperceptible, but it was definitely there, an event in the east face that looked slightly out of place. Well, it wasn’t so much out of place as it was too perfectly in place. It looked like a small notch in the irregular edge of the mesa. There were dozens of similar grooves on the mesa face–but this one was somehow too deliberate, too intentional. Still unsure, I walked on and just as I lost sight of my notch in the shadows a huge trench appeared before me on the mesa. I had reached Double Negative.

Though it appears as a spatial continuum, Double Negative is actually three parts: two cuts and the space between them. The northern cut was the notch that first caught my eye; the southern cut was the trench at my feet. Standing now at its southern end before hiking through it, I took in Double Negative‘s full 1500 foot length, 30 foot breadth, and 50 foot depth. It is literally monumental, requiring Heizer and his crew to remove 240,000 tons of the mesa itself.

When they finished the job forty years ago, Double Negative looked different. Its edges were sharp, its walls were planar, its floor was smooth. I wondered if it seemed hubristic and arrogant back then, and maybe even violent.

These qualities still linger about the place, but not in a negative way. Today, it is a much softer work. Its edges are eroding, its sides are crumbling, its floor is filled with rocks. Mormon Mesa is slowly recovering from artistic intervention.

There is something very American about Heizer’s bold gesture. Like the remains of the Oregon Trail that I saw a few days later, Heizer’s mark on the land resonates with Manifest Destiny and the great push “to overspread the continent.” Like the natural monuments that distinguished the Americas from Europe–the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, the Great Sand Dunes–Double Negative possesses an inherent, sublime grandeur.

In Double Negative‘s inevitable disintegration, the work provides a moving commentary on the inevitable decline of the American Empire. For me, this is what makes it so satisfying. It is brimming with meaning, but it is empty and absent. It offers nothing more than a place to contemplate the mesa and the sky. If offers nothing less than a place to contemplate the history of human settlement.

I hiked out of the trench and sat for awhile on the mesa’s edge, happy with the solitude, the blazing sun, the dominance of nature.

It was getting late and I was only 70 miles north of Las Vegas so I walked back to the car, which looked like a toy against the immensity of the mesa, and drove slowly back to civilization.