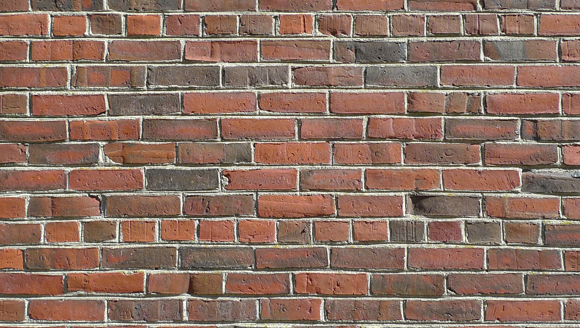

Outside Exeter Library 6 July 2012

In Megalopolis, Jean Gottmann called the I-95 corridor the “Main Street of the Nation” to convey its significance to the vast conurbation of the northeastern U.S. That’s a useful way of thinking about the longest north-south interstate in the country, its nearly 2,000 miles connecting major population centers and an almost continuous fabric of sprawl. But we all know that Main Streets and Interstates are very different sorts of roads–perceptually, symbolically, and physically. Main Streets go through places; Interstates, except for the notorious ones that gutted urban centers in the 1960s, go around places. This is certainly true of the stretch of I-95 that I know best, between Washington, D.C. and Bangor, Maine. North of New York, once the road cuts through Washington Heights and the South Bronx, it goes around Stamford, around New Haven, around Providence, around Boston, around Portsmouth, around Portland.

If the town is big enough and the by-pass is proximate enough, you can discern the skyline from the highway. In Stamford and New Haven, buildings grew up around the interstate–Roche-Dinkeloo’s Knights of Columbus being the most thrilling example, or the most appalling, depending on how you feel about Brutalism.

In smaller places, the towns are invisible from the highway, but for hints provided by the signage overhead, as at Exit 4 in New Hampshire, which discreetly directs drivers to the Portsmouth Traffic Circle. If you’re not paying attention, you might miss New Hampshire entirely. Of all the states I-95 passes through, NH has the least mileage–only 16 miles between Massachusetts and Maine. That gives you about 15 minutes to experience the granite state in all its live-free-or-die glory, but on 95 from the North Shore to Piscataqua River there is precious little that makes an impression, notwithstanding the irresistible allure of tax free booze at the State Liquor Outlet.

This time of year, I always look forward to pulling off at Store #76 near (not in) Hampton Falls to stretch my legs, let the dog out of the car, and lay in a supply of libations for DesignInquiry’s annual Vinalhaven gathering. I also look forward to savoring the aesthetic absurdities of the big red barn by the side of the highway, complete with fake cupolas, faux sliding doors, and vinyl clapboards.

I’d like to believe the New Hampshire Liquor Commission chose this homage to the architecture of New England agriculture as a way of acknowledging the historical importance of farmer bootleggers during Prohibition, but I know better–those vestigial elements stopped signifying decades ago. Though maybe they still have some vague associations with country folk and country manners, the friendliness of buying booze in a barn serving to assuage the guilt of out-of-town scofflaws transporting whiskey and wine across state lines.

I didn’t spend much time contemplating this interpretation during my most recent trip to Store #76 because for once I intended to actually see something of New Hampshire beyond the I-95 corridor, briefly leaving the “Main Street of the Nation” for an actual Main Street. Somehow though, whether we were overwhelmed by the wine-in-a-box options or distracted by the sampler gift packs of tequila and scotch, by the time we pulled back onto the highway for the six mile drive to Exeter it was later than I hoped.

As High Street gave way to Main Street (via Water) Exeter revealed a downtown of tidy commercial buildings and upscale storefronts. Other than a sweet little beaux-arts bandshell (built 1916), there was nothing remarkable about the place, which is perhaps what made it so remarkable–an exceptionally well-preserved urban fabric from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Residential neighborhoods are scattered about the commercial core, containing more than a few 17th and 18th century houses. This isn’t surprising since Exeter was founded in 1638, by religious exiles from Massachusetts. Among them was Edward Gilman, who came up from Hingham, where the Old Ship Meeting House is located.

A visit to the Old Ship, the nation’s oldest house of worship in continuous use, was last summer’s off I-95 adventure en route down east. Attempting to go inside the meeting house last June, though it was clearly closed for renovations, we managed to set off a motion detector alarm and had to hide in the burying ground until the cops left. However undignified this may have been, it afforded an excellent vantage point for photographing the building in the late afternoon.

Edward Gilman of Hingham moved up to Exeter several decades before the Old Ship Meeting House was built in 1681. By then, his children and grandchildren had become prominent in Exeter as merchants and shipbuilders. A century later, in 1781, they had sufficient wealth to endow the newly established Phillips Exeter Academy and to donate a large tract of land to serve as its campus. It was the academy that brought us to Exeter.

The 19 buildings Ralph Adams Cram designed on the campus circa 1914 have an undeniable appeal–not only because he was a native of Hampton Falls, location of New Hampshire Liquor Outlet #76, but because the classicism of the academy’s colonial revival structures is not what you’d expect from the king of collegiate gothic. Still, there’s no use pretending that we were there to see anything but the library.

The 19 buildings Ralph Adams Cram designed on the campus circa 1914 have an undeniable appeal–not only because he was a native of Hampton Falls, location of New Hampshire Liquor Outlet #76, but because the classicism of the academy’s colonial revival structures is not what you’d expect from the king of collegiate gothic. Still, there’s no use pretending that we were there to see anything but the library.

The Exeter Library is so iconic it’s the kind of building that haunts your dreams, a perfect embodiment of Lou Kahn’s semi-mystical utterances about space, form, and meaning. “Architecture comes from the making of a room,” Kahn declared in 1971, the year the library was finished, in what seems like an apt description of the building’s great central space, a raised, multi-level atrium of platonic voids and concrete geometries serving as a symbolic gathering space for a learning community.

Or so I’m told. By the time we got to Exeter in the late afternoon, the library was closed. Instead of the expansive money shot on the left (courtesy Daderot on Wikimedia Commons), I got the occluded off-kilter shot on the right. But if, in being forced to peer through glass entry doors, I was denied the breadth of the atrium, I got something just as good, and just as important to Kahn’s work: a shift in focal distance from the communal to the individual, from the monumental to the ceremonial. Even from the outside, this is evident in the gently curving concrete stairs that Kahn clad in travertine to mediate human engagement with the building.

Or so I’m told. By the time we got to Exeter in the late afternoon, the library was closed. Instead of the expansive money shot on the left (courtesy Daderot on Wikimedia Commons), I got the occluded off-kilter shot on the right. But if, in being forced to peer through glass entry doors, I was denied the breadth of the atrium, I got something just as good, and just as important to Kahn’s work: a shift in focal distance from the communal to the individual, from the monumental to the ceremonial. Even from the outside, this is evident in the gently curving concrete stairs that Kahn clad in travertine to mediate human engagement with the building.

One notices the meeting of concrete and travertine because Kahn, characteristically, used a limited palette of materials that rendered each one more powerful, and nowhere is this clearer than in the library’s load-bearing brick facades. Locked out of the library, we had ample time to ponder them in detail.

Chamfered corners reveal the structural conceit of the self-supporting walls; granite sills are deep enough for comfortable sitting; segmental arches have a subtle modulation; piers grow more slender and bays grow wider as the load lightens up the facade; inset teak panels look like spandrels but are actually built-in study carrels.

Twenty years ago Vincent Scully changed the discourse about Kahn by placing his work in the context of “the ruins of Rome.” Walking around the Exeter Library the evocation makes sense, given the muscular strength of the brick walls and shadowy spareness of the covered walkways.

But as I moved from one passageway to another, I couldn’t help wondering if I’d have been thinking of the Markets of Trajan without Scully’s prompt, because up here in New England all that brick could just as easily conjure ruins closer to home–in Lowell, in Manchester, and even in Exeter itself. Between 1901 and 1965, Peter and Alfred Eno supplied bricks for buildings throughout New Hampshire, including many on the Phillips Exeter campus, from a manufacturing plant on the southwest edge of town. When the company folded in the mid-60s, the school purchased its entire inventory of 2 million bricks and required their use for the new library and the adjoining Elm Street Dining Hall, also designed by Kahn.

[The latter building, an oddly effecting composition of archetypal forms, instantly evokes Venturi’s work from the same period (think Mother’s House and Fire Station No. 4) along with a heavy dose of Aldo Rossi and Giorgio de Chirico. Long overshadowed by the library, the Dining Hall is discussed in an excellent 2004 Future Anterior article by William Richards: “Razing the Exeter Dining Hall: Pros and Kahns.”]

The library’s exterior consists of 420,000 waterstruck Eno bricks, laid in a common bond with a header course every eighth row. However accurate that straightforward description (and one wonders who counted the bricks), it does not come close to capturing the actual quality of the exterior of the Exeter library.

Waterstruck bricks are made of very soft wet clay packed into moulds prepared with water and sodium silicate. As the wet bricks are turned out of their moulds the dragging effect leaves its trace on four sides. During the firing process, those drag marks are transformed into a patina whose texture and color have an astonishing variety, depending on the swiftness of mould pull and, especially, on the brick’s location in the kiln.

From a distance the library facade appears to be a uniform surface of red brick, from close-up you realize it’s the opposite–a hearty mottle of reds, browns, and blacks, of gashes, perforations, and dings. The variety of color and texture was even more pronounced in the late afternoon light, and with nothing to contemplate except the facade of the closed library, we began to take in each variation and every irregularity.

The culled bricks, whose use Kahn must have specified, were the most moving. Melted during the firing process, such bricks were generally rejected as imperfect, but at Exeter, the more severe the distortion the more the culled brick enlivened the facade in a sculptural way, giving it an enticing tactility.

There is a parallel in the effect Alvar Aalto created with clinker brick on the Baker Dorm at MIT (1937-40), but in Cambridge the tweedy irregularity of the bricks extends to the entirety of the facade. In Exeter, by contrast, the culled bricks pop out of the surface at such unexpected moments that after awhile looking at the masonry makes you giddy. That’s when you realize you’ve started to fondle the wall.

“What do you want, Brick?” Kahn famously asked. Supposedly the brick replied “I like an arch,” but on a warm summer afternoon in Exeter, the brick might have been satisfied with something less complicated. We certainly were.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.