In the Wake of the Half Moon 31 July 2009

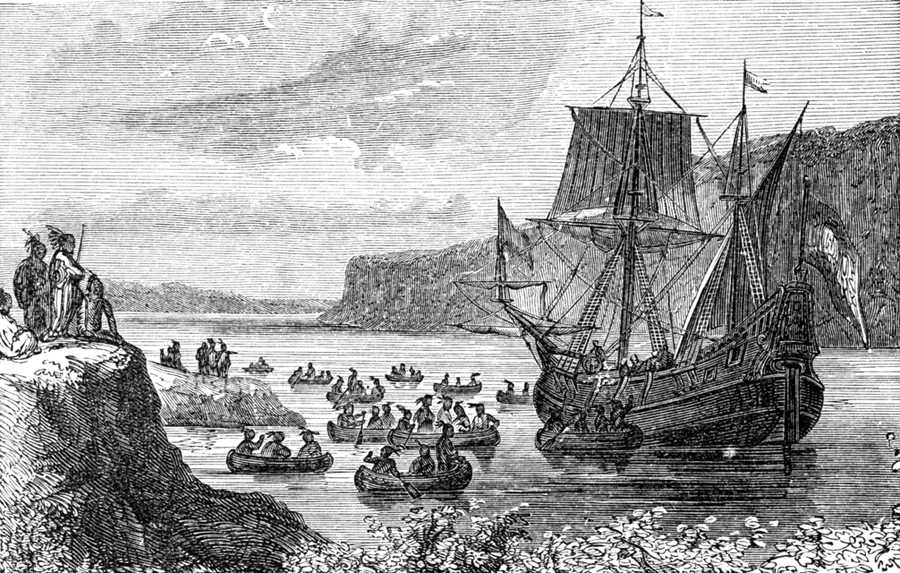

In the summer of 1609 Henry Hudson and a crew of twenty Dutch and English sailors entered what is now New York Bay and sailed their sloop, the Half Moon, up the wide river that today bears the explorer’s name. Four hundred years later, I jumped in the river after them.

Hudson was looking for an uncharted passage to China. I was looking for a buoy-marked passage to 79th Street. He had to keep an eye out for potentially dangerous natives. I had to keep an eye out for potentially dangerous flotsam. Several of Hudson’s men were assaulted by the Algonquin. I didn’t encounter so much as a discarded condom. It took Hudson all day to sail from the bay to the tip of the island. It took me twenty-five minutes to swim from Cherry Walk to the Boat Basin.

History has not recorded what Hudson was thinking as he passed the island’s western shore. I was thinking about its transformation from deciduous forest to concrete jungle, from sandy beaches and salt marshes to sea walls, highways, monuments and towers. Well, that and how to avoid getting kicked in the face by the swimmer in front of me.

Still, one’s perspective of the city changes from the water. Only on the water do you get a sense of the true extent of New York’s aquatic self, 578 miles of coastline slung out over three large islands and a spit of the North American mainland. Only in the water do you get a sense of the true extent of New York’s post-industrial self, a vast recreational waterscape in place of what was once a hardworking waterfront.

Moving swiftly through the current, surrounded by kayaks and pleasure craft, you realize how thoroughly the city of homo faber has become the city of homo ludens. And this might explain why there were nearly 4,000 other people in the water on the day I did in the New York City Triathlon.

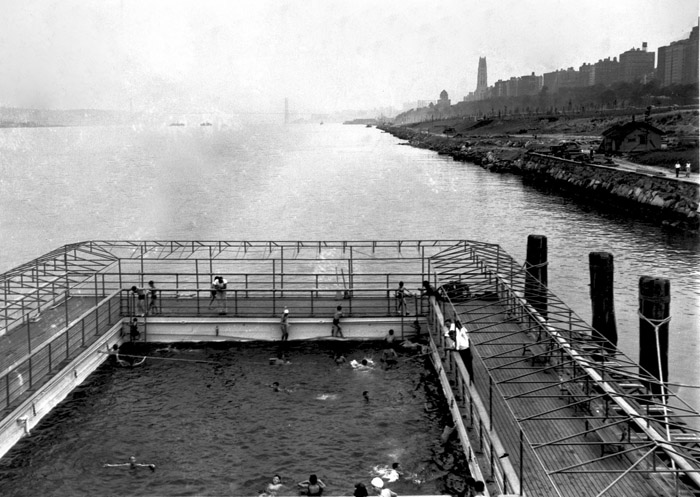

Until the middle of the 20th century, swimming in the NYC-stretch of the Hudson was a normal summer activity. While the city lacked the lifeguard beaches found in the Palisades on the New Jersey side of the river, from the 1870s to the 1940s it had a series of floating baths that moved around on pontoons to the apparent delight of swimmers up and down the west side of Manhattan.

A perfect example of nature tamed, the baths were filled with the half-salt/half-fresh water of the river itself while protecting swimmers from the river’s considerable tides, currents, and depths. The last of the floating baths were moored at West 96th Street, near where I started my swim. The triathlon’s temporary pier, with its steel decking and banners, seemed like a fitting, if less paternalistic, heir.

When the floating baths were finally decommissioned at the start of WWII, the water quality of the Hudson was seriously degraded by sewage and industrial waste, most notoriously PCBs, and this pollution continued until long after the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972. By then the Hudson’s heyday as a working waterfront was long over and the city settled into a gloomy state of fluvial disregard.

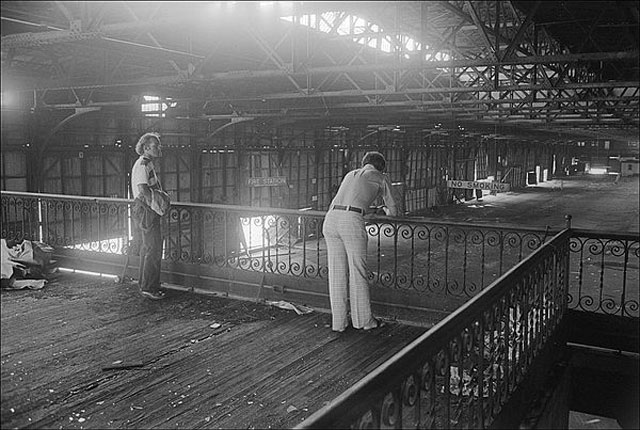

This isn’t really surprising: between the highway and the rotting piers was an urban no man’s land that had appeal only for those reveling in the sweet moment of liberation between Stonewall and AIDS (and joyously documented in Gay Sex in the 70s).

Even Riverside Park had seen better days. Though Robert Moses rebuilt this “wasteland” in the 1930s, covering the New York Central tracks to give pedestrians, and of course automobiles, access to the waterfront, by the 1970s the esplanade was so decrepit and crime-ridden that when Riverside Park turned up as the setting for a climactic gang battle between the Baseball Furies and the Warriors, Walter Hill’s 1979 cult classic starts to seem like cinema verité.

Thirty years later, there’s a café where the Warriors bested their enemies. It’s only open until 11 pm but most nights in the summer the crowd lingers until much later, finishing their beers and hanging out with their dogs.

It’s the same up and down the waterfront, which is now part of a city-wide greenway. The rebuilt piers have lounge chairs and wifi; the industrial detritus is landmarked and turned into art; the esplanade is planted with the same species of trees and grasses that Henry Hudson would have seen back in 1609.

Past is somehow prologue walking the river in 2009: the Machine Age Manhatta of Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler’s film meets the primeval Mannahatta of Eric Sanderson’s digital reconstruction. And the Hudson River is cleaner than it’s been in a century; so come on in, the water’s fine.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.