Preamble Ramble around the Garden State 28 February 2009

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

On a sunny, cold Saturday at the end of January we got in the car and headed from the Upper West Side to New Jersey. It’s a short trip, about 5 miles, but it always seems momentous. Maybe it’s the drama of the Hudson as it narrows between Fort Washington and Fort Lee. Or maybe it’s the drama of O.H. Ammann’s George Washington Bridge, whose towers are so high and mighty (at 604 feet) they made Le Corbusier nearly giddy when he saw them in 1935. In the bridge, Corb wrote, “steel architecture seems to laugh.” And even today, if you drive across the upper deck or look at it from a distance on those rare nights when the towers are fully illuminated, it’s easy to understand why he called it “the only seat of grace in the disordered city.”

The sublimity of cables and beams aside, the momentousness of the journey must also have something to do with crossing a state line. Anyone who grew up in Middle America surely remembers the ritual of the state line–honking the car horn, holding your breath, etc. These rituals probably stem from the significance of state jurisdictional boundaries, especially as depicted in popular culture.

The rangers had a homecoming in Harlem late last night; and the Magic Rat drove his sleek machine over the Jersey state line.

Those are the first lines of Bruce Springsteen’s Jungleland, the final, nearly operatic track on his 1975 LP Born to Run. It hardly needs mentioning that the only way to drive any machine from Harlem to Jersey is to cross the Hudson on the GWB (we will grant the Boss artistic license for stretching the boundary of Harlem about a mile north). Thirty plus years later, notwithstanding the expansion of the megalopolis, regional scale, and tri-state areas, the state line still means something. And this is probably why, for me, driving to New Jersey remains a bigger deal than driving to Brooklyn, even though I’ve been working in the Garden State since 2001 (of course, I don’t drive to work and that probably figures in here somehow, too).

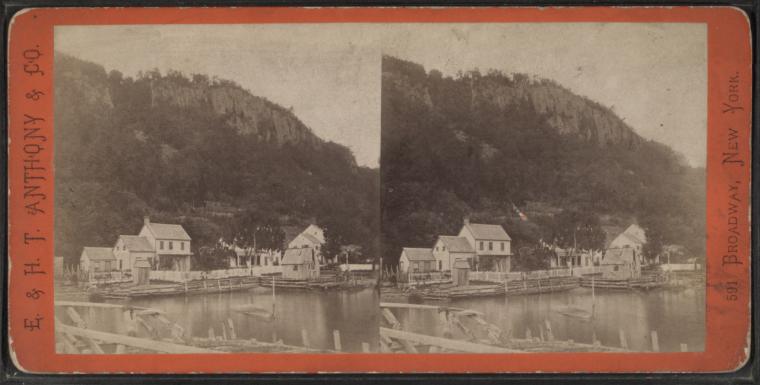

Our destination that morning was the New Jersey Palisades, the sheer stone cliffs that rise from the west bank of the Hudson River. They are imposing things, the Palisades, 550-feet tall with a natural grandeur that holds its own against the man-made mountains across the river. They’re so big that during WWII someone proposed building a bomb-proof shelter inside them; Hugh Ferris even did renderings of the wacky scheme–part Piranesi, part Boullée, with fighter jets thrown in for good measure. Our plan was to hike along the top of the cliffs to enjoy expansive views of the river and the Manhattan skyline.

We started in the parking lot at the Ft. Lee Historic Park. Just west of where we parked the car, the Continental Army had attempted, in vain, to prevent the British from taking control of the Hudson in 1776. Just west of where we parked the car, our hardy band attempted, in vain, to locate the trailhead for the Long Path in 2009. The posted maps were strangely inscrutable, as were the blazes. They all seemed to indicate that the trail left the park, followed a busy feeder road for the bridge, and then proceeded up the GWB’s north walkway, closed to pedestrian traffic since 9/11.

Though this made little sense we reluctantly gave it a try and soon found ourselves climbing the steep steel stairs that lead to the bridge walkway. A locked gate prevented us from accessing the walkway itself, but there was a small deck leading to another set of stairs, and then to what was clearly a marked hiking trail–one foot on the bridge and another foot in the woods. It was a happy threshold and I noted it to myself as a transitional moment. I didn’t realize it would be the keynote for the day.

As we walked through the woods following the trail north, I kept waiting for the traffic noise to grow fainter; it didn’t. But we hiked on contentedly because the sun was shining and the snow was crunching underfoot and because we kept thinking the trail would change just beyond the next big tree. After about a mile, the trail did change: it revealed the backside of a gas station. Despite the unlovely vista it presented from the woods, some of our party availed themselves of the facilities. I, meanwhile, grappled with the dawning realization that we were spending our idyllic escape-from-the-city morning smack in the middle of a highway right-of-way.

The gas station we’d stumbled on was a service plaza of the Palisades Interstate Parkway. It was built in the late 1940s when just about anything with a planted median could get away with calling itself a parkway, but this one really was a road through a park. In the late 19th century local (wealthy) landowners concerned about the devastation of the Palisades from quarrying and timbering (trees cut on top of the cliffs were tossed down the side for transport on the river) formed a park commission. By the 1930s both the Regional Plan Association and John D. Rockefeller supported the idea of a cliff-top roadway running through a continuous recreational preserve.

It was Rockefeller who donated the land we were hiking through that morning. The problem was that his 700 acres gift, though 13 miles in length was less than half mile in width. So up on top of the cliffs, even with a wooded buffer, the parkway remains a sort of keening presence. But this just might be appropriate for hiking in New Jersey, the state with the country’s densest population.

After awhile the din of the traffic made me smile and I thought of Benton MacKaye, father of the Appalachian Trail. MacKaye was a dedicated conservationist but he was also a pragmatist who wanted to balance nature and civilization. He would have understood the nexus of footpath and parkway as inevitable and necessary. A bit further north, that nexus became even more pronounced.

As the trail pulled west it came right alongside the roadway, so close that we were now hiking the parkway and I was tempted to stick out my thumb. The blazes were no longer painted on trees but on the tops of sawed-off sign posts. This may not have been the “deep dramatic appeal” that MacKaye envisioned for the modern hiker, but it had some kind of perverse appeal nonetheless. This may have been simply the appeal of the spectacle we presented as we walked with a dog along a highway. After about a third of a mile the novelty wore off. At the next junction we turned away from the parkway and followed a road down the side of the cliff to the river’s edge.

The Shore Path has pleasures of its own: little sand beaches, stone stairs into the water, and, of course, dynamite views of Manhattan. On this morning, however, the footing was bad, alternating between ice and mud and we had to abandon it. Instead, we walked south along the river road. Known officially as Henry Hudson Drive, this is an old style road that was built for pleasure driving beginning in 1916. Under the bridge and out of the park, we were on back on Hudson Terrace, the feeder road where we picked up the Long Path trailhead. We walked up the hill to the top of the cliff where we left the car. The sidewalk, extra-wide and newly built, felt like the last link in the funky trail system we’d been exploring. Not quite urban, not quite rustic, but the perfect footpath for a day of hiking in Jersey.

this is brilliant blog. keep it up and be safe…

I am enjoying your trip vicariously!! Please contact if you get anywhere near San Francisco, would love to see you. 831-359-5043.