Genius Loci in Acadia 29 August 2009

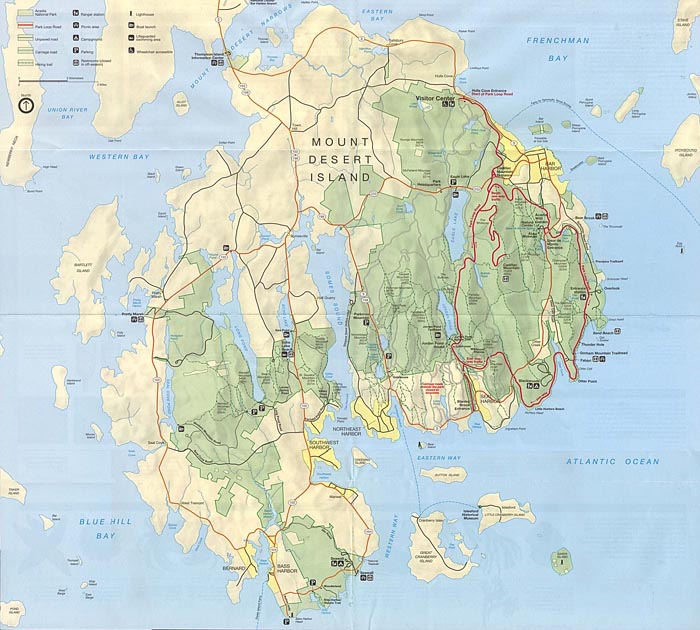

On an island off the coast of the North American mainland, near the narrows of Somes Sound, across from Norembega Mountain, between Fernald Point and Clark Point, a few steps from the Atlantic, in Southwest Harbor, Maine (at 44.278º North and 68.311º West, to be precise), one is easily, happily, and phenomenologically seduced by the spirit of the place.

The sight of the mountains and forests, the smell of evergreen and seaweed, the feel of the shells and the rocks, the taste and the sound of the ocean. These are why summer people come to the Maine coast, and certainly why they’ve been coming to Mount Desert Island since the first rusticators arrived in the decades after the Civil War.

By train, steamer, and ferry from Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, they arrived eager to consume the same landscape that Thomas Cole and Frederic Church captured in their oils and watercolors. Beginning with their village improvement societies and ending with their successful effort to create the first national park east of the Mississippi, the rusticators shaped Mount Desert Island as surely as nature and geography.

The earliest white settlers on the island, who arrived mainly after 1759 when the English drove the French out of Acadia, lived with and from the land and the water. They were the first to harvest the island’s natural resources and to make Maine “Maine.”

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

But it was the rusticators who understood how to exploit the genius loci for their pleasure, profit, and eventually for the public good, as is still evident in what they built across the island–mountain trails and town paths, scenic drives and carriage roads, inns and resorts, piers and houses. These were built for the seasonal tourists, but they became the essence of the place.

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

…..

The cottage I’m renting in Southwest Harbor is called “the Legacy” because it’s been passed down a generation or two since it was built in the 1940s, but it could just as easily refer to the Acadia passed down by the Eliots and the Rockefellers.

Though the pitch of the roof and the knowing placement of the picture windows nod to mid-century architectural taste (the next house down the coast, by contrast, is an over-scaled Dutch Colonial from the 20s), the granite fireplace, pine-framed rooms, and cedar shake exterior evoke the rustic rusticity of the rusticator’s image of Down East Maine.

But placeness here, as everywhere, means more than building materials and manicured wilderness; it also involves food culture and traditions. The rusticators, like their island hosts and the native Wabanaki before them, were locavores avant la lettre. Fresh haddock, cod, oysters, clams, mussels, and, of course, lobsters.

Though dining in the rough was more a necessity than a choice in the 19th century, it has considerable appeal even in the 21st, at least where lobster is concerned since the whole point of eating at a pound is that, at least in theory, you are guaranteed the freshest bottom feeders possible.

Even if the pound functions as a dealer/middleman, there’s the added value of the picturesque–the harbor, fishing boats, stacked pots and buoys, picnic tables, gulls, mosquitoes, Teva sandals, Life is Good t-shirts, etc.

This year I bought steamers and cherry stones from a guy called Rat who was selling them out of an old refrigerator in a cluttered garage next to a mildly ramshackle house in Bar Harbor. I was attracted by his sign, especially his use of “safe shellfish” as a descriptor.

While it is true that many areas on the island are closed to digging because of paralytic shellfish poisoning, the need to advertise bivalve safety is both amusing and depressing, sort of like service stations advertising “clean restrooms.”

For the record, I ate two dozen of Rat’s clams for dinner with no ill effects though steaming them in an entire bottle of vernacchia di San Gimignano might have killed whatever toxins lingered in those mollusk filters.

Rat told me that he used to sell his clams to Pectic Seafood before it moved off the island. I knew Pectic. It was in a little trailer of a building right next to the house where its owners lived, up a quarry road well off the main highway in Mt. Desert. When the sons took over the business they closed this location and opened a big store close to the Wal-Mart sprawl of Route 3 in Ellsworth.

While the economics of year-round traffic probably drove this decision, Rat and I both understood that something had been lost in the relocation. He declared the original Pectic a real “mom-and-pop operation,” the sort of place that appealed to the summer people he described as “those folks in Northeast Harbor with their Philadelphia accents.” His place, by his own admission, was a little too rough for their tastes, but not for mine apparently, though I wasn’t sure if it was the New York plates on my car or my lack of a Main Line lockjaw that met with Rat’s approval.

When I told Rat that I liked his sign on Route 102 he laughed that I was about the only person who did. The Japanese tourists told him he needed neon; the village improvement types told him he needed nicer lettering. The authenticity of place is in the eye of the beholder.

Next: genius loci accinium angustifolium; or, where the wild blueberries grow

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.