Flatbush Start to Finish 29 May 2012

Stay on Flatbush Avenue long enough in either direction and eventually you hit water, but it wasn’t always like that. One of Brooklyn’s oldest streets, Flatbush Avenue used to be landlocked. In the 17th century it was a country road connecting disparate Dutch farming villages, including Vlacke Bos, from which the avenue takes its name.

In the 18th century, the Flatbush Road was sufficiently improved to require serious defense during the Battle of Long Island (the Americans held the pass against the Hessians thanks to the trunk of an enormous oak, but the British attacked from the rear and the patriots went down in defeat). In the 19th century, under the auspices of the Brooklyn and Flatbush Plank Road Company, it assumed close to its present route, inland through the heart of what was not yet completely the City of Brooklyn (those Dutch villages didn’t allow annexation until around 1895). It was only in the 20th century that Flatbush became the 10-mile long, multi-lane, traffic-choked corridor it is today, its extensions towards the water coinciding two more times with the ambitions of the expanding metropolis.

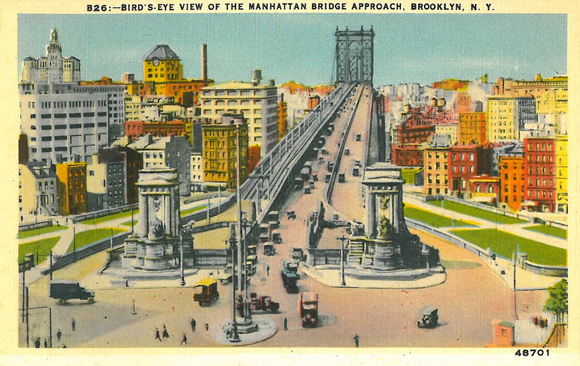

Driving on Flatbush on a typical Saturday night, it can seem as if the only reason they built the segment from Fulton Street to the East River was to accommodate double parking in front of Junior’s. But by the time the cheesecake king open his doors in 1950, this stretch of Flatbush was nearly half a century old, the product of civic boosterism and urban development that typified the decade after consolidation in 1898. The Flatbush Avenue Extension, as it is still called, was completed in 1906 in anticipation of the opening of the Manhattan Bridge a few years later. As originally designed, Flatbush Avenue began at the foot of the bridge, emerging from the upper roadway between two massive granite pylons.

Though not as commanding as the triumphal arched, colonnaded set piece Carrère and Hastings designed for the Manhattan side, their Brooklyn pylons provided the borough’s newest gateway with some serious Beaux-Arts monumentality. At least that’s how it looks in the postcards. Robert Moses demolished the pylons in 1961 during his epic construction of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway.

Among the piles of granite the Powerbroker dismissed as “ornamental masonry” were 12-foot tall allegorical figures of Brooklyn and Manhattan sculpted by Daniel Chester French. After the City Art Commission spared the pair, they moved further down Flatbush and onward to Eastern Parkway, finding a permanent home in front of the Brooklyn Museum.

In substituting highway exit for grand entrance with the callous urban disregard that marked his later career, Moses robbed Flatbush Avenue of a dignified commencement. But three decades earlier, on the opposite side of the borough, at the opposite end of the avenue, Moses achieved the opposite effect, providing Flatbush with a thrilling conclusion.

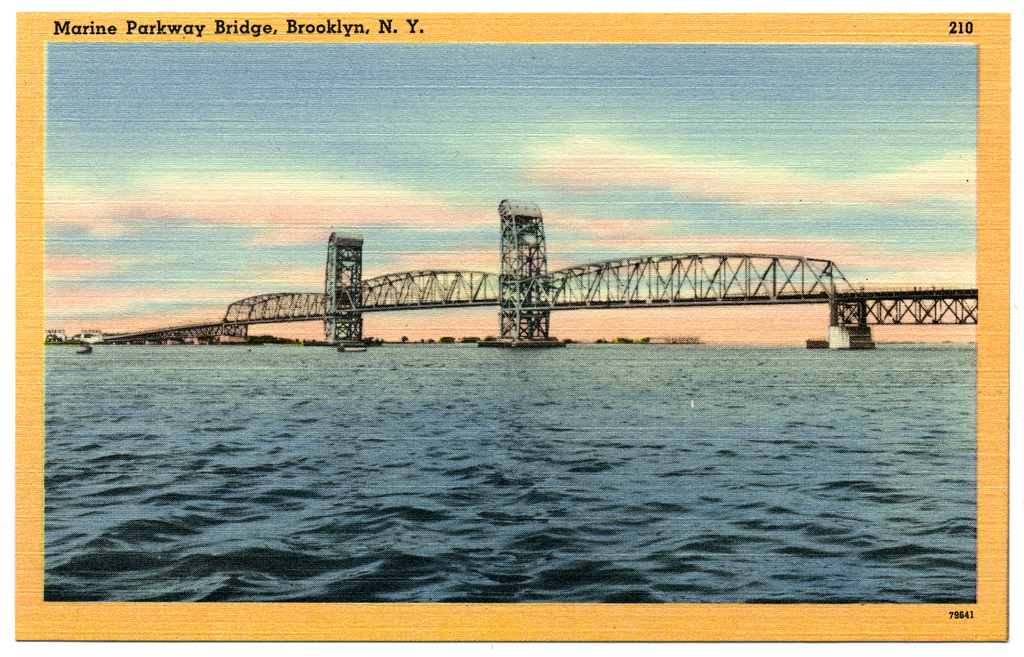

The Marine Parkway Bridge links southern Brooklyn to the Rockaways. The Times declared it a “motorway to seaside” when the bridge opened in 1937, which made sense since Moses built the bridge to to provide car access to the beachfront recreation areas he had just completed at Jacob Riis Park.

Emil Praeger and the firm of Waddell & Hardesty engineered its vertical lift span, the longest in the world at the time. Aymur Embury, the Powerbroker’s favorite architect, designed the towers, terminating them with giant scroll-like forms that house the wheel mechanism in a sort of streamlined combo of classical volute and Chrysler hubcap.

Approached at grade from Flatbush, the bridge really seems like a continuation of the avenue. Past the toll plazas it rises gently over the mudflats and salt marshes. Then, mid-span, above Jamaica Bay, an urban climax: look south beyond the peninsula and you see the Atlantic Ocean; look north beyond the flatlands and you see the skyline of lower Manhattan (Jersey City, too).

If you’re driving it’s hard to appreciate the effect. Better to take to the bridge on foot or bike, which has economic as well as scenic advantages. This being a Moses’ project, the Marine Parkway Bridge was constructed by a public authority, and tolls have been charged from the beginning. Originally, the toll for motorists was 15 cents and back then even the cyclists had to pay. Moses charged them a dime. Today, cars pay $3.25 in each direction, but bikes get to cross for free.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.