Fitness and Civilization 22 May 2009

Power walking, it turns out, is one of the hallmarks of the American civilization. I had seen plenty of it in Los Angeles: folks in groups of two and three, arms swinging with their strides while making their way slowly but determinedly through the hills of Griffith Park. I hadn’t paid much attention to these people maybe because I was too busy gasping for breath while attempting to run through the hills of Griffith Park, or maybe because their approach to urban fitness was so familiar as to be unremarkable.

Once I left the coast, the power walkers gave way to hikers, rock climbers, and mountain bikers, at least from my admittedly narrow vantage point. In Moab, in southern Utah, the wildness of the geologic landscape precludes anything but extreme physical activity.

In Salt Lake City, in northern Utah, the streets are scaled to the turning radius of a team of mules and a pack wagon, producing a grid with blocks 1/8 mile in length and decidedly unwelcoming to pedestrians.

There were highly organized power walkers in Colorado Springs, but they turned out to be cadets marching in formation through “the terrazzo” at the heart of the Air Force Academy.

Military discipline has never seemed as seductive as on that campus, designed by Walter Netsch and SOM in the mid-50s. I kept thinking of a line from an old Joe Jackson song: “you can wear the uniform and I can play along.”

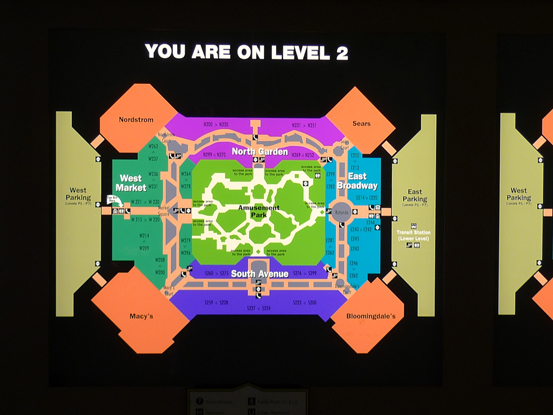

At any rate, I started to notice the the power walkers again as I got closer to the middle of the country. With 2.5 million square feet, the Mall of America near Minneapolis is so large that even most the casual shopper is transformed into a power walker.

It takes a certain amount of exertion to get all the way from Nordstrom’s to Bloomingdales to Camp Snoopy, even without a grade change.

It takes a certain amount of exertion to get all the way from Nordstrom’s to Bloomingdales to Camp Snoopy, even without a grade change.

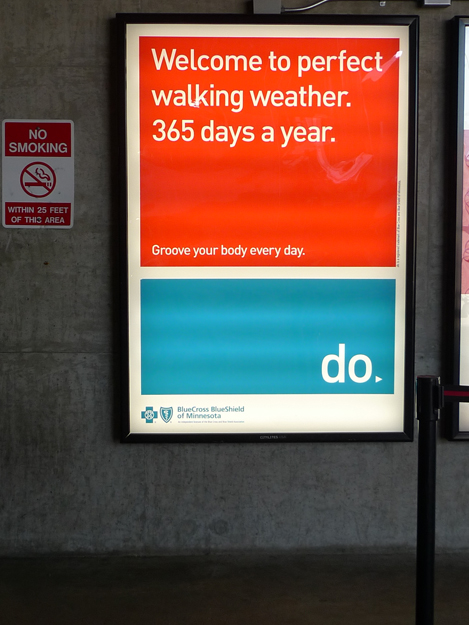

At a bridge between the parking garage and the mall, an advertisement for BlueCross and BlueShield of Minnesota acknowledged this fact. The Gruen effect becomes a cultural condition.

Once I crossed the Mississippi the power walkers emerged in force. At the John Deere World Headquarters in Moline, Illinois they were doing laps in the visitor pavilion of the Saarinen-designed campus (1964) at the very beginning of the work day.

I wondered why they weren’t outside since Hideo Sasaki’s landscape is full of mature shade trees and winding paths. Perhaps they liked the building too much to leave.

When I was in downtown Moline the cashier at the John Deere gift store asked me if I had been out to the HQ and told me that her mother “had the privilege of working in that beautiful place for nearly twenty years.” So maybe those John Deere power walkers were diehard modernists, you never know.

Nearly 300 miles down the river from Moline, and right across the river from St. Louis, I stopped off to see the remains of the civilization at Cahokia (950-1200 AD). The Monks Mound, at the heart of the grand plaza, is the largest earthwork in the Americas. It rises to a height of 100 feet and its base covers fourteen acres. When I got there in the early evening it was still quite hot so I walked slowly up the stairs on the south face stopping at each terrace to admire the view and wipe the perspiration from my face.

Each time I paused I was lapped by a fast walker flexing barbells with each step. With her white sweatpants and orange t-shirt, she looked marvelous against the green grass and the blue sky, but it was her re-purposing of the ancient monument that I appreciated the most.

Looking at the St. Louis Arch from the top of the mound, I thought of Lewis and Clark and the opening of the west. Cahokia used to be the frontier; now it’s a para-fitness course.

POST-SCRIPT: In the middle of writing this, I spotted more power walkers. Up with the sun, they were making their way through a sidewalk-less subdivision in central Ohio, taking advantage of the coolness of the morning. I stopped counting at 22.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.