El Vocho 7 January 2010

When I was growing up our cars were transportation, not lust. According to family lore, when my father was a soon-to-be-married young man he used his savings to buy a plot of land instead of a 1958 MG. The family cars that followed were unusual by the standards of 1960s America, but they were hardly objects of desire.

I don’t remember much about the Anglia, except that it was some sort of British Ford. Two Peugeots came after, not counting the gold Buick company car that came with my father’s organization-man lifestyle in the early 70s.

The first Peugeot was a 404 with a 4-speed column shifter that cried out for driving gloves. That car was burgundy with a matte finish and it had tailfins the way France had rock and roll, kind of groovy but a pale imitation of the real thing.

The second Peugeot was more conventional: a four-door sedan with a floor-mounted shifter and a sloped but squared-off rear; it was notable only for its paint job: a subtle metallic color called Cascade Green. It only looked green in the right light, and even then what your eye perceived was just a hint of sea foam—imagine Scope mouthwash diluted with five parts water.

The first car that was really mine, and that really caught my fancy, was a 1972 Volkswagen Beetle.

Bought at least a decade before “pre-owned” entered the lexicon, this faded yellow bug was a stripped down model, not a superbug. It had a flat windshield and four-on-the-floor with an AM radio and so much body rust underneath that the driver’s seat sagged towards the ground. Without a piece of cardboard on the floor, I could look down and see the blacktop, in a close approximation of Fred Flintstone’s motoring style. Though this induced vertigo at high speeds, driving the interstates of the northeast, between Philadelphia and Northampton, was always thrilling.

Once, I left the yellow bug at school over winter break and returned at the start of the spring semester to find it buried under two feet of snow. I dug my way in with a broom and had to use a hairdryer on the frozen lock. I put the key in the ignition and, just like the scene in Sleeper where Woody Allen finds a 200-year-old VW in a cave, the air-cooled engine turned over on the first try.

Sadly, my bug died soon after, though with great flare. In a catastrophic engine failure, it spewed oil all over the eastbound lanes of the Mass Pike on a final road trip to Boston just after final exams at the end of my senior year. I don’t remember ever having sex in the back seat of that bug (though I did stuff a queen size futon in it once), but thinking about it produces the same sort of romantic haze that accompanies so many male automotive reveries.

Though I didn’t realize it at the time, that Volkswagen was my real introduction to serious design, and all the social and political baggage that comes with it.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

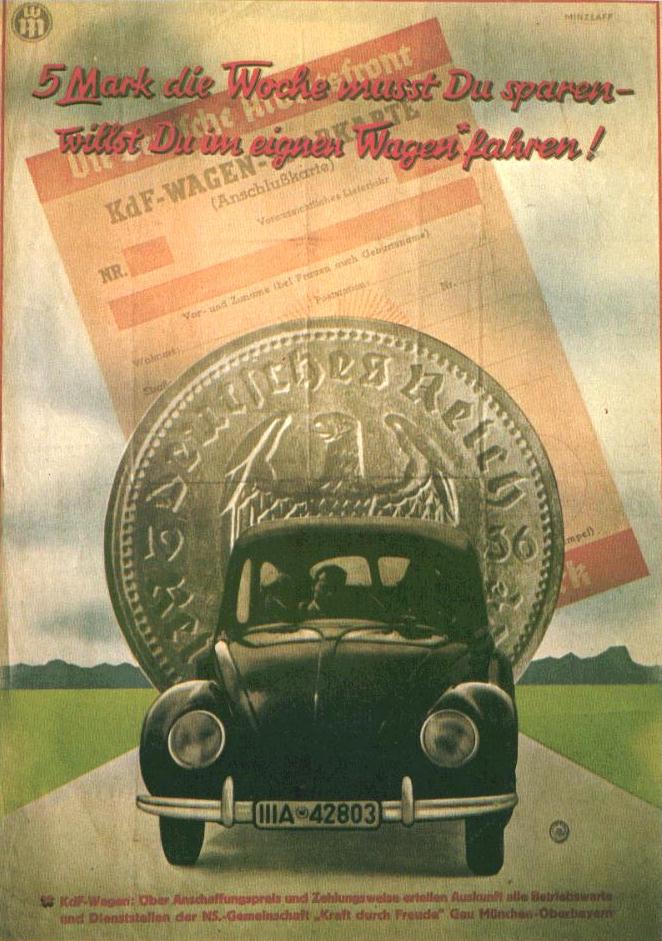

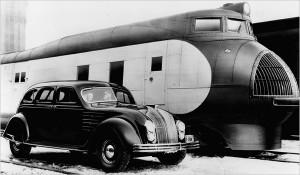

Perfected by Ferdinand Porsche and Erwin Komenda with the financial backing of the Third Reich, the body of the Type 1 Volkswagen was an unmistakable product of late 30s styling. It had much in common with Carl Breer’s Chrysler Airflow and Hans Ledwinka and Paul Jaray’s Tatra T77.

.

..

.

..

Like them, the VW was an early attempt to create a car body that was aerodynamically efficient, or at least looked like it was. Because the VW’s bulbous body became so familiar, so iconic, in the second half of the twentieth century, folks stopped noticing its streamlined details a long time ago.

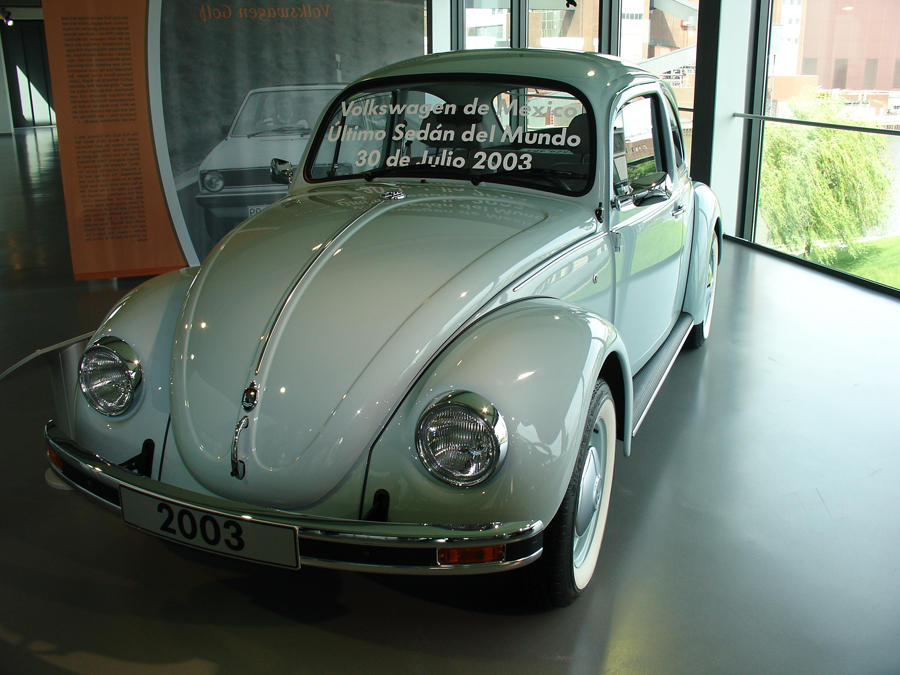

But they were there when the first production VW hit the streets in 1938 and they were still there when the last Type 1 rolled off the assembly line in 2003, nearly twenty-two million inverted teardrops, contoured fenders, and chrome speedlines later.

I’ve been thinking about VWs because I spent the holidays in Mexico, including a night in the city of Puebla, where the last Type 1 was built, in a factory that opened in 1954 after German immigrants to Estado Puebla lobbied Wolfsburg to begin Mexican production.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Aside from talavera tile and mole, VWs must be Puebla’s most culturally significant export.

That original plant is still in operation: modernized and re-tooled, it’s the only factory that produces the much-hyped, though ultimately underwhelming, new Beetle. (The debut of the Concept 1 prototype in 1994 occasioned my first and only purchase of Car & Driver and Road & Track.)

Touring Puebla at the end of 2009, it seemed clear that building beetles, like being declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was making a serious contribution to Puebla’s economic prosperity.

While wandering through a gentrifying indigenous neighborhood outside Puebla’s centro histórico, I discovered the familiar VW logo on all the street signs, corporate PR in the service of a barrio’s rebranding campaign.

Mostly, though, it’s the bugs themselves that make the biggest impression, whether in sleek black or tricked up for a fiesta.

Everyone knows that VWs are legion in Mexico but it was still a wonderment to see so many of them, especially in the capital where their broad metallic curves make a fine roving counterpoint to the churrigueresque ornament that’s as ubiquitous on the buildings as the bugs are in the streets.

I’m not sure if it was Christmas, or nationalism, or just standard color options, but there were green, red, and white bugs everywhere I turned.

.

.

.

.

.

.

And I can honestly say that they filled me with as much joy as freshly baked roscas de reyes (also green, white, and red) and freshly fried churros.

.That last bit might be a slight exaggeration because those were damn good churros. I’m sure it is no coincidence that they were served up at churrería as old as the VW itself.

El Moro opened in 1935 and, unlike Volkswagen, its proprietors have had the good sense to leave well enough alone. The churro, like the bug, is perfect in its original form.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.