Again with the huts 27 March 2011

In 1753 a Jesuit priest named Marc-Antoine Laugier writes an essay in which he posits a primitive hut, une cabane rustique, as the origin of architecture. The trunks of four trees growing together in a forest form a rough structural framework; above, their branches grow into a perfect triangular pediment; atop this, their leaves provide an enclosing roof: “et voila, l’homme logé.”

As it turns out, Laugier’s natural hut is not too far off the mark: the trabeated construction of the ancient Greeks did have its origins in simple wood forms that may have been inspired by canopied trees. But Abbé Laugier is less concerned that his primitive hut be understood as an archeological artifact than that his primitive hut be understood as a theoretical idea. At the height of the Enlightenment, this little cabin is utterly polemical, and the man lodging inside it is no less a personage than Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s l’homme sauvage. Just as Rousseau’s noble savage exists happily in a primordial paradise unsullied by the artificiality and corruption of society, so too Laugier’s primitive hut. And in its rustic materiality and unadorned simplicity it embodies a culture of romantic authenticity—the deliberate antithesis of studied, cosmopolitan sophistication.

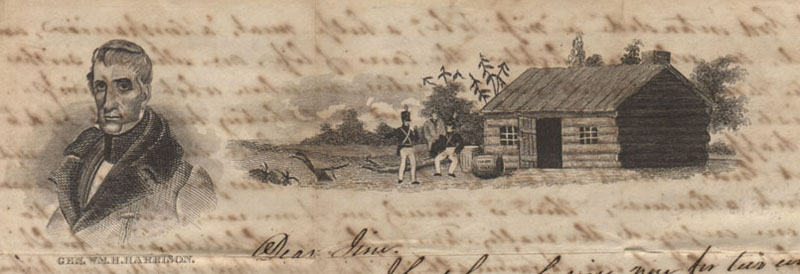

Roughly a century later, the association of simple man and simple cabin becomes fodder for the US political machine during the successful presidential campaigns of William Henry Harrison in 1840 and Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Harrison is a member of the eastern wealthy elite, but this isn’t playing well with the same rowdy electorate that put Andrew Jackson in office.

So, his handlers invent a frontier past for him: log cabin as birthplace, “the house our fathers lived in.” Theirs, not his: from the landed gentry of Virginia, Harrison was born in the big house at Berkeley, a Tidewater plantation.

The jig is up shortly after Harrison’s inauguration: would a true frontiersman have caught a cold and died after only a month in office?

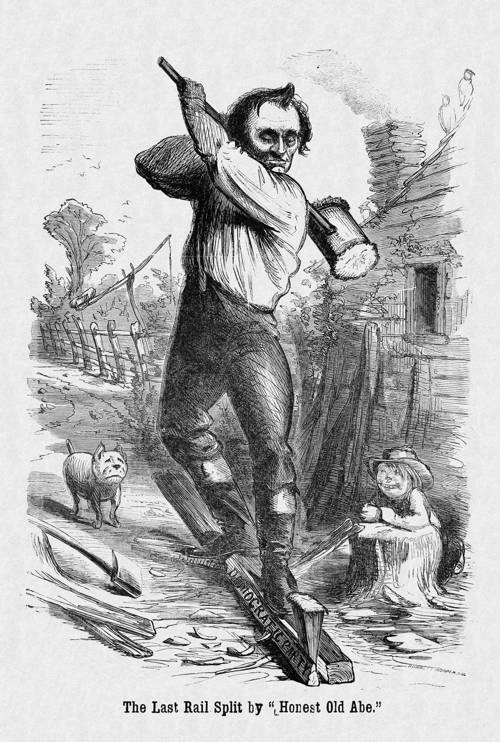

Two decades later, Abraham Lincoln is the real deal: he was born in a log cabin in the backwoods of Kentucky. As befitting these humble origins, he is unaffected and plain-spoken. And during his presidential campaign he is known by the nickname “rail-splitter,” a reference to his chores as a hard-working young frontiersman.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

His log cabin origins are less than a source of pride for Lincoln since they represent the abject poverty that characterized his early life and from which he deliberately escaped. This matters little to the political mythmakers, especially after his assassination in 1865. Though numerous reformers, including Frederic Law Olmsted and Harriet Beecher Stowe, recognize the log cabin for what it is—a primitive hut that is rude and not romantic, the log cabin penetrates deeper into the American psyche.

In 1893 a Lincoln Log Cabin is moved to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. That Abraham Lincoln never actually lived in this cabin is beside the point for the throngs of visitors who touch its rough-hewn exterior as they would the relics of a martyred saint. The cabin was lost after the exposition closed and was reportedly used as firewood.

The CCC rebuilds the cabin in the 1930s on its original site on the Illinois farm where Abe’s father and stepmother moved in the 1830s when the future president was already a lawyer in Springfield. Apparently, there is great interest in historical accuracy, such as it can be gleaned from the photographs that exist, and we can picture the CCC boys resisting their usual tendency towards making things neat and tidy, struggling mightily to recreate the sag of the roof, the irregularity of the chinking, the shagginess of the shakes.

Meanwhile, back at Lincoln’s Kentucky birthplace, his humble hut has become the stuff of legends, enshrined in a classical temple designed in 1910 by a young John Russell Pope channelling von Klenze channelling the Parthenon. Sinking Springs may not be the Danube but the effect is the same, a bluegrass Walhalla for the first memorial ever built to Lincoln.

Inside, is the ur log cabin, supposedly built of the actual logs of the actual structure that witnessed the actual arrival of Abraham Lincoln into this world.

When the cabin is finally reconstructed inside the memorial in 1911, Pope thinks it is too big for the interior and insists that it be reduced in size for easier circulation. American pragmatism trumps cultish sanctity. Pope is right to be unconcerned: in 2003 the National Park Service used dendrochronological analysis to determine conclusively that all of the cabin’s logs post-date Lincoln’s birth by a good four decades. Today, the Park Service refers to the structure without fanfare as “the symbolic cabin.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.