November 8th, 2016 14 November 2016

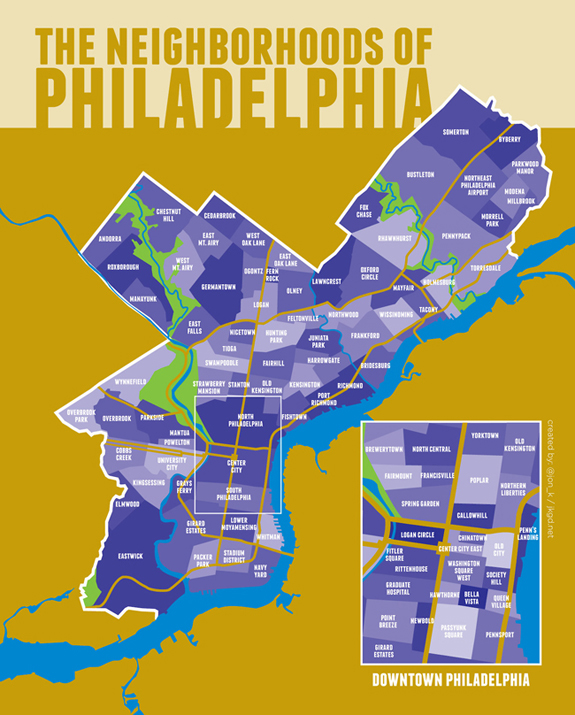

I spent Election Day in Philadelphia with a friend, giving people free rides to the polls through the Drive the Vote! project. We were driving folks in Philadelphia because Pennsylvania was, as they say, in play, and because I’m from Philadelphia and my parents still live there. Our territory was meant to be northwest Philly. It’s the area I know best, having grown up in Chestnut Hill, the city’s most northwestern neighborhood. But Chestnut Hill is not the sort of place where many folks need rides to the polls because if they can’t get to the polls under their own steam, they generally have the means to arrange for transport. So we drove out of Chestnut Hill hoping to get in range of a voter in need of driving (Drive the Vote! was using Uber-like technology to connect people with cars and people casting ballots).

As we travelled slowly southeast along Germantown Avenue, areas of long-standing prosperity gave way to expanded fields of gentrification, which gave way to districts of just barely hanging on marginality, which finally, and monumentally, gave way to the wide variegated swath of impoverishment and abandonment of North Philadelphia (as in north of Center City). North Philly is not one single place; it’s made up of distinct neighborhoods, all of them shaped as much by social and economic evolution as by physical geography.

As we travelled slowly southeast along Germantown Avenue, areas of long-standing prosperity gave way to expanded fields of gentrification, which gave way to districts of just barely hanging on marginality, which finally, and monumentally, gave way to the wide variegated swath of impoverishment and abandonment of North Philadelphia (as in north of Center City). North Philly is not one single place; it’s made up of distinct neighborhoods, all of them shaped as much by social and economic evolution as by physical geography.

Annexed into the city in the 1850s, North Philadelphia became a center of industry in subsequent decades. By the turn of the last century, much of its gridded extent was densely built with blocks of row houses, mostly two stories, and with considerable typological variety. Blocks of red brick houses are followed by blocks of buff brick houses. One side of the street has projecting bays and porches; the other side has flat fronts and stoops. Some blocks have elaborate cornices; others have decorative columns.

My mother grew up in one of those North Philly row houses near 27th and Allegheny (that’s her on the stoop in 1953), on a street where the block’s original homogeneity was long ago replaced by idiosyncratic individualizations that accumulated over the decades: tin siding, vinyl siding, asphalt siding, awnings, astroturf, and so on (as is clear in the google street view). My grandfather made his own contribution when he added a railing and milk bottle holder to his Etting Street stoop, thus preventing members of his family from posing in that spot for any subsequent photographs they might have taken before my grandmother sold the house and moved in with us in 1974.

My mother grew up in one of those North Philly row houses near 27th and Allegheny (that’s her on the stoop in 1953), on a street where the block’s original homogeneity was long ago replaced by idiosyncratic individualizations that accumulated over the decades: tin siding, vinyl siding, asphalt siding, awnings, astroturf, and so on (as is clear in the google street view). My grandfather made his own contribution when he added a railing and milk bottle holder to his Etting Street stoop, thus preventing members of his family from posing in that spot for any subsequent photographs they might have taken before my grandmother sold the house and moved in with us in 1974.

While we might look for meaning in these individual physical markers, it’s their aggregation across North Philly that creates the strongest impression of the changes that have taken place here in the last half century, as factory closings, block busting, absentee landlordism, and generational poverty left their mark on these row house blocks in predictable and devastating ways. North Philadelphia today is less the “inner city” of political dog whistles than “the Ghetto” in the complex, even classical sense that Princeton sociologist Mitchell Duneier lays out in his important recent survey, Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea. As we drove across North Philly on ElectionDay, an extended landscape of urban decline seemed to stretch out in every direction, revealing itself with numbing effect as we passed block after block of empty shells, boarded up buildings, and run-down row houses.

But we weren’t just passing through that day, and any deadened detachment we might have been feeling ended each time we pulled up to a particular house to pick up the specific North Philadelphian residing at that address and in need of a ride to the polls. A few of our fellow citizens needed rides because they had mobility issues, but more of our fellow citizens needed rides because they were registered to vote in election districts far away from their current places of residence. A few of our fellow citizens had missed the deadline to change their registrations, but more of our fellow citizens were contending with the realities of housing displacement that the economically insecure live with every day. Some of our fellow citizens couldn’t afford to pay the fare for the multiple subways and buses they’d have needed to take to their polling place–and it didn’t help that the recently-settled SEPTA strike had screwed up their weekly passes. Some of our fellow citizens couldn’t afford the time such a journey would take–we drove one young woman nearly 14 miles across town. But every one of our fellow citizens was determined to exercise the franchise and vote in the 2016 presidential election, and it was a patriotic privilege to help them make this happen just by getting behind the wheel with a smartphone.

It was long past dark and after 7:30 when we pulled up at our final polling place, a public recreation center in North Philadelphia, in a row house neighborhood not far from Temple University. The line to get inside snaked across the playing field and out onto the sidewalk, but since poll workers had assured everyone that if they were on the line before the polls closed at 8 pm they would be able to vote, the mood was more festive than restive. As we stood there with the crowd (because our voter also needed us to drive her home from the polling place), it seemed like the anxiety of the previous months was being slowly washed away, not by a certainty of victory, but by the mere presence of our fellow Americans waiting to vote in the City of Brotherly Love.

It was long past dark and after 7:30 when we pulled up at our final polling place, a public recreation center in North Philadelphia, in a row house neighborhood not far from Temple University. The line to get inside snaked across the playing field and out onto the sidewalk, but since poll workers had assured everyone that if they were on the line before the polls closed at 8 pm they would be able to vote, the mood was more festive than restive. As we stood there with the crowd (because our voter also needed us to drive her home from the polling place), it seemed like the anxiety of the previous months was being slowly washed away, not by a certainty of victory, but by the mere presence of our fellow Americans waiting to vote in the City of Brotherly Love.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.