Mall Walking, part I 22 April 2009

___________

Driving from San Francisco to Los Angeles not long ago I headed inland and stopped off in Fresno. The state’s fifth largest city had not been on my list of must-see places, but Paul Groth at Berkeley had assured me it was worth the detour in order to walk the Fulton Mall.

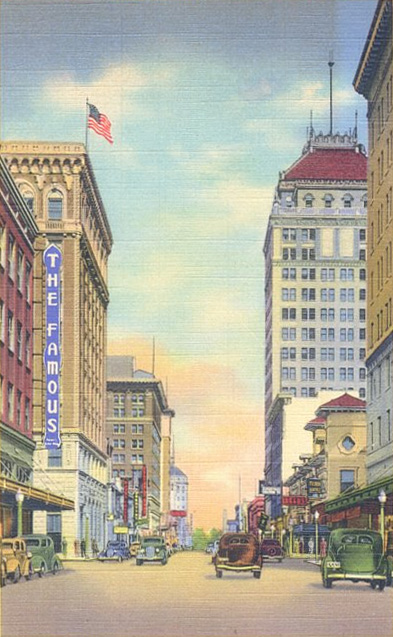

Fulton Street was once the heart of downtown Fresno, lined with its tallest buildings and its largest shops. As in so many other U.S. cities, by the 1960s Fresno’s commercial life had shifted from the center to the periphery. In 1964 city leaders hoping to reverse this trend (and capture their share of federal urban renewal dollars) turned to Victor Gruen to prepare a master plan for Fulton Street’s redevelopment.

Though best known as the inventor of the suburban shopping mall, Gruen made a significant contribution to post-war urban design by promoting the idea that U.S. cities could balance the reality of the street and the dream of the sidewalk. The result was “pedestrian modern,” as David Smiley has smartly called it, a practice of remaking downtowns through superblock planning that acknowledged the necessity of the automobile while embracing the ideal of the walker.

In Fresno, Gruen’s master plan called for the elimination of car traffic on six square blocks of Fulton Street in the central business district and the transformation of those streets into a landscaped pedestrian corridor. He also specified the regularization and modernization of Fulton’s storefronts to create a unified streetscape and the construction of garages to absorb the displaced on street parking.

Garrett Eckbo was responsible for implementing Gruen’s scheme, and the design he produced encompasses an imaginative variety of berms and beds, pavilions and benches, and fountains and pools. These features, mostly rendered in concrete with organic forms, are set into a paved field accented with meandering rubble work and smooth tiles. As a whole, Eckbo’s design has the easy abstraction you would expect from the father of modern landscape architecture and the artful informality you would want for an urban strolling destination.

And strolling is exactly what you want to do when you arrive at the Fulton Mall, especially if it is a hot, arid day in the San Joaquin Valley. I entered the mall in the late morning, crossing Van Ness on Merced Street and passing one of the mall’s original parking garages (Alastair Simpson, 1964). This is a low slung building whose scale and location indicates discretion rather than concession to the automobile.

As soon as you turn into the mall proper you sense the coolness provided by mature vegetation. After forty-four years the ample reach of olive trees and the dense canopy of wisteria make the mall’s benches and pavilions exceptionally pleasant places. They make you want to stop strolling and start sitting.

And quite a few of Fresno’s pensioners and youth were taking their ease on the mall the day I was there. I can’t show you how they looked in situ because they scurried away when they realized I had a camera pointed in their direction. The younger men in baggy jeans and do-rags seemed especially desirous of getting out of the frame.

They weren’t the only ones suspicious of my camera. While admiring the modernized ground floor of the Guaranty Building–all goldenrod paneling and groovy lettering–I was surrounded by several burly men whose anxiety increased the more I ignored them. They kept asking me how I was doing. I responded happily that I was just fine and continued my observations. Apparently, this was not satisfactory. They phoned a superior: “There’s someone here walking around taking pictures.”

Several other burly men showed up wanting to know what I was doing. This seemed obvious but I thought it prudent to explain: “I’m walking around taking pictures.” Their eyes narrowed with suspicion: “Of what?” they demanded. “The Fulton Mall,” I responded cheerfully. Before they could reply I launched into a lecture about pedestrianization and modernism. Their eyes glazed over with boredom.

As they shuffled away, one of them mumbled that they should tear the whole thing down to prevent the homeless from sleeping on the benches; another mumbled that I shouldn’t be allowed to take photos of a government building. It turns out that the Guaranty’s main tenant is the US Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Their exit made it easier for me to sit and admire the fountains and the sculpture adorning them. Many of these works were created by local artists in conjunction with Eckbo’s office. They were paid for privately by Fulton Street merchants and other Fresno business people who were convinced that a program of public art would make the Fulton Mall a true civic amenity. Most of the work is unsurprising late modern abstraction cast in bronze, a friendly hybrid of Brancusi, Noguchi, and Moore. While most of the work looks smashing in the setting Eckbo provided for it, there is only so much pedestalled bronze I can take.

Stan Bitters’ ceramic fountains, at four different sites on the mall, were a welcome change. Apparently, they are meant to evoke the irrigation pipes that made Fresno an agricultural center but they have a Mediterranean whimsy that, in addition to reminding me of the work of Roger Capron, was sufficiently far removed from the metallic geometry scattered about the mall.

The same can be said of Joyce Aiken’s and Jean Ray Laury’s mosaic benches. In the entirety of the Fulton Mall their panels of bursting color fields and syncopated rhythms are matched only by the wild graffiti of the former Gottshalks Department Store.

Though Gottshalks only recently filed for bankruptcy, the Fresno-based chain abandoned its Fulton location two decades ago. Now the prominent building, dating to 1914 and flamboyantly modernized in 1948, is occupied by what is essentially a swap meet. And while the graffiti matches the exuberance of the building, its presence is a reminder of Fresno’s decline.

For the historian, that decline has obvious benefits: the Fulton Mall is almost miraculously intact and frozen in time–which is why the Downtown Fresno Coalition thinks it is a good candidate for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (it was nominated in 2008 but is still under review). But however pleasant the Fulton Mall may be for admiring modernist urban planning, it’s not much good for shopping these days. Many storefronts are empty; many are occupied by cut rate retailers serving a struggling clientele; still others are occupied by social service agencies catering to the same clientele. Restaurants offering cheap lunches for employees of the nearby courthouse and county offices seem to be doing better, but just barely.

Fresno built the Fulton Mall to forestall decline, but the city didn’t realize it was fighting the tide of history. Now there are plans to rip out the mall and reintroduce traffic to Fulton Street. The city is still fighting the tide of history. Design, alas, rarely fixes economics–it didn’t work in 1964 and it’s not likely to work now.

Coming Soon: Mall Walking, part II: from Burbank to Glendale

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.