Taking Things Seriously 15 April 2009

A friend gave me a book with this title for Christmas; a collection of short essays about miscellaneous, yet meaningful objects, it’s one part Roland Barthes and one part Antiques Roadshow. Passing through a whole country worth of significant stuff, and with plenty of rumination time behind the wheel, I have been taking things pretty seriously these days. I’ve also been trying to avoid accumulating anything worth taking seriously.

Driving around with a few dozen books, miscellaneous electronics, and footwear for situations both professional and recreational, I’m hardly traveling light. Still, I like the idea of being mythically unencumbered in a Kerouac-boxcar-king-of-the-road sort of way.

This is why on my trip so far, I’ve mainly acquired things that are consumable (Tennessee whiskey, Texas strawberries, Arizona apple cider, California grapefruit) or ephemeral (tourist pamphlets, souvenir postcards–my favorite is from San Xavier del Bac with a die cut Latin cross).

Though I was sorely tempted by an array of aqua colored kitchen items at a junk shop in the Antelope Valley, I opted to leave the display intact for other roadside voyeurs to enjoy.

Sometimes, however, the desire for material possession is so acute that resistance is futile and one has no choice but to give in. Across 19 states and 7700 miles, this has happened to me exactly twice.

______________________

In New Orleans, Louisiana I acquired a hollow concrete block. In Glendale, California I acquired a pink plastic bunny. The block and the bunny have nothing much in common beyond mass-production and me, but by virtue of my acquisition their fates are now intertwined.

Block

I first spotted the concrete block in situ. We were driving along Highway 61 in Mid-City when a building that could credibly be mistaken for mid-career Corbusier came into view.

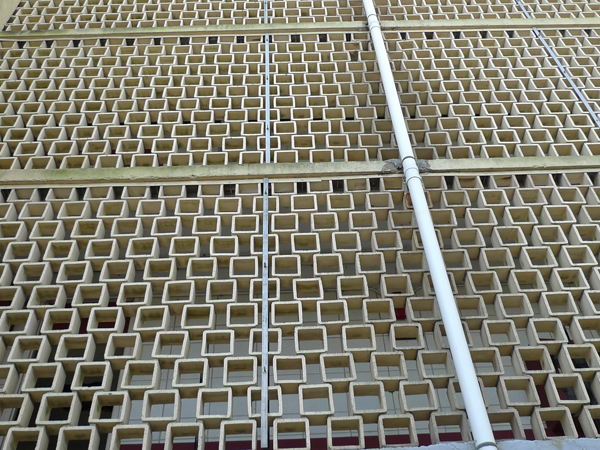

Back in the day, it had clearly been a hotel and a swanky one at that. (Thanks to Karen Kingsley, I now know that it was the Pan-American Motor Hotel designed by Curtis & Davis in 1958.) We pulled to the back to have a closer look and were astonished to find monumental free-standing stair towers and a six-story concrete block sunscreen facing open-air galleries.

The blocks were tinted yellow to set them off from the building’s exposed concrete frame and, I suppose, signal their decorative function. Laid in staggered courses with minimal mortar they seem to float when viewed from the ground. Though fifty years of hurricanes had rendered the courses a bit jiggy, this animated the individual blocks and the whole screen seemed to twitch and pulse with mid-century optimism.

The building is being converted to senior housing and the foreman at the site invited us to take a look around. He also told us that Katrina had so weakened the sunscreen that it was being removed and the galleries would be enclosed. I pictured the dull infill façade that would take its place. I thought about the artificial climate control that would trump the original, stylish responsiveness to New Orlean’s subtropical climate–even in our era of supposed sustainability.

I felt a mournful sort of sadness wash over me, and it only increased as I looked around to see that piles of blocks were already littering the site, waiting to be sent to some distant landfill. It was like going to the ASPCA and feeling all those needy puppies tugging at my heartstrings. I decided to take one with me.

Then I decided not to: it seemed silly to carry off a ten pound CMU and then cart it around the country. My companions, however, insisted that I follow my original impulse and Julie marched off to make a selection. She returned triumphant and handed it over. Up close I could appreciate the rounded corners that made it friendly, the rough texture that captured the light, and the true heft that made it the building block it literally was. I basked in the phenomenology of the thing, and then realized how dirty it was making my hands.

Walking back to the car to put it in the trunk, I enthusiastically mentioned how great it would look on the extruded aluminum bookshelves in my Manhattan apartment. Julie quietly suggested that it would look even better on the Ikea bookshelves in my Newark office. She may assist me in procuring an obscure object of desire, but that doesn’t mean she wants to live with it.

In the meantime, the block is back outside, where it belongs. From a temporary perch on a terrace in Los Feliz it happily frames cypress and eucalyptus trees and a spectacular view of downtown L.A.

Bunny

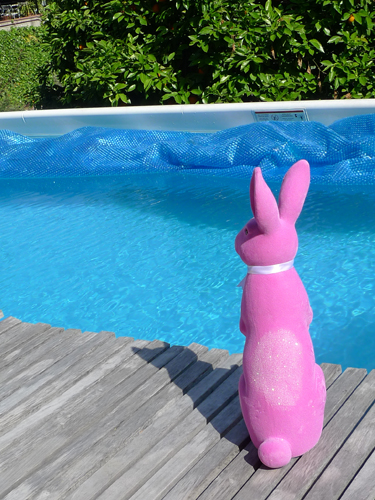

Walking through an open-air shopping plaza off Brand Boulevard in Glendale on the day before Easter, I spotted the bunny in the seasonal window display of a store that was straining hard at a kind of packaged pseudo-cool. At first I didn’t realize it was actually for sale; it seemed impossible that I could own a thing of such perfect compact oddness, but there was another bunny on the half-priced table. Not only could I buy this bunny, I could buy it at a fifty percent discount.

The bunny is 18 inches tall and stands alert, yet relaxed with one paw hanging limply and the other pulled close to his torso. His pose is as close an approximation of a contrapposto as a bunny could be expected to manage. I won’t go so far as to say that the bunny resembles the David, but there is a quiet dignity about the way he gazes knowingly into the distance, ears cocked in anticipation of something out there on the horizon. It’s probably not Goliath, but the bunny still seems brave.

The bunny is made of hard plastic, but he is covered in hot pink flocking that gives him a certain resemblance to both the Velveteen Rabbit and a basement rec room from c. 1970. Around his neck is a white ribbon that is dapper, but superfluous. Across his back is a dense patch of sparkles that suggest the far away roller disco glamour of a more innocent time.

If Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami opened a factory in China, this bunny would be the result (without the ribbon). But that’s what makes the bunny so compelling. A factory in China made the bunny without any help from international art world superstars. My host in L.A. suggested we find the factory and start selling the bunny at Moss. I liked the idea of hundreds of 18 inch pink bunnies in those lofty white interiors. I also liked the idea of a solitary 18 inch pink bunny boldly resisting the detritus of my everyday life.

Neither block nor bunny is what Thoreau called “necessary of life,” but I am compelled to give this account of them lest they be mistaken for the “accumulated dross” that Henry David so vigorously condemned during his life in the woods. The concrete block cost me nothing. The plastic bunny cost me $6.49 plus tax. Given how good they look together, with their contrasting colors, textures, and forms, I’d say this was was a bargain.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.