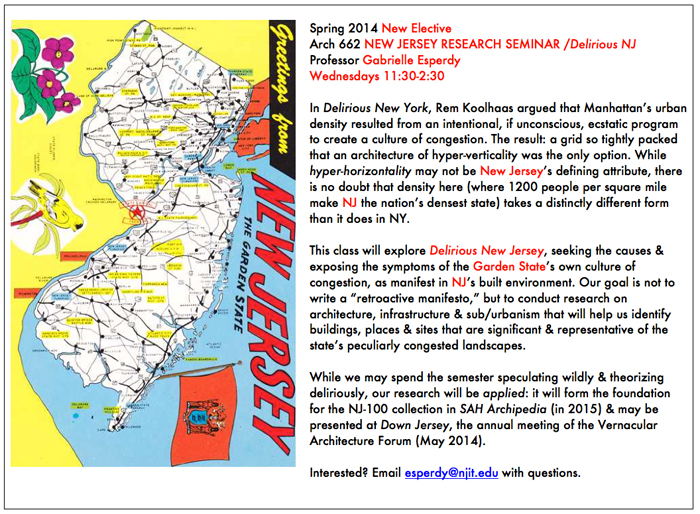

Delirious New Jersey

DELIRIOUS NEW JERSEY looks at NJ’s built environment to seek the causes and expose the symptoms of the Garden State’s cultures of congestion. NJIT architecture students conducted this research in spring 2014 under the guidance of Professor Gabrielle Esperdy. Each project includes a summary of the research [intro image & text] and gallery of POSTCARDS [captions-are-content].

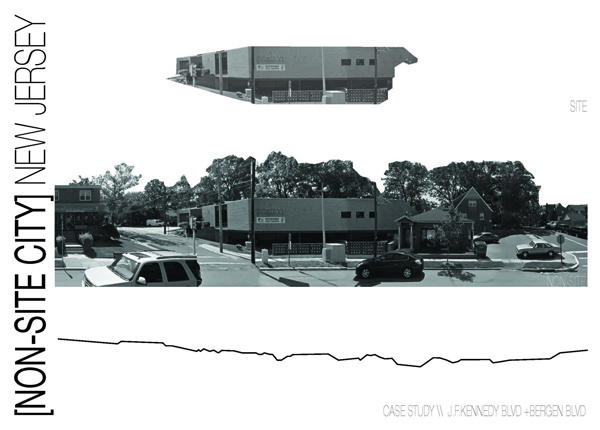

NON-SITE CITY: New Jersey through JFK Boulevard & Bergen Boulevard [GABRIEL CANIZO]

How does one start to find New Jersey as a place? It is hard. New Jersey has many identities that one cannot pick one. So ask yourself is there one identity that could hi every thing together. I believe so.

An argument can be made the New Jersey has every component to be considered more like a city than state it, but without city marker/sites. It is a non-site city. How can this be, one could ask. Well New Jersey is in between New York City and Philadelphia. Many times it is know as the in between, crossover, or drive through state. Ever since their founding, these two cities have been generally growing. These two cities’ relative proximity naturally lends them to grow towards each other and eventually forming one megalopolis. What is in between, New Jersey? So all aspects of city building growth I’ve been happening in New Jersey for a long time. Yet it is not a true city, it is a non -site city.

What do I mean by non-site city? Well the language is borrowed from the artist Robert Smithson. Robert Smithson uses yet his ideas about site and non-site to create an artistic polemic about New Jersey. This artistic language has value in terms of codifying to research and identity or non-identity of a place. A site is it is an actual place. It has identity and gives identity. A non-site is an abstract of a place, in metaphor for a place or site. Therefore, a non-site city is an abstract of a city, in metaphorical city, a city without an identity.

The research is looking at New Jersey to reveal if it is a non-site city. This done through the analysis of a road and its streetscape, J.F. Kennedy Boulevard + Bergen Boulevard, that passes through multiple towns/cities and even crosses county lines. This streetscape shows that every town/city the faces J. F. Kennedy Boulevard + Bergen Boulevard has at least one city marker it being a school, firehouse, post office, etc. The marker by itself is a site identifying where you are at the building scale. Everything in between the sites is city components, abstracts of cities, things that make up cities but are not of a particularly named city. They are non-site, without identity. When one starts to look at the streetscape of the whole faces J. F. Kennedy Boulevard + Bergen Boulevard together, the city markers/sites merge with the non-site infill with no ability to pull the markers from the non-site. Therefore, the markers become non-site at this scale. The town/city identities no longer matter since that since they cannot be read in the landscape, linking them all of them together as non-site city.

How does this apply to the scale of New Jersey? J. F. Kennedy Boulevard + Bergen Boulevard at the state level is just a state regional road. The city component language seen in the case study is something that is all over the state and the same logic can be up scaled. New Jersey is a non-site city; this is where I am led to by the research. All-City components are there to make a city without the identity; it is an abstract of the city, autonomous of title, non-site, a non-site city. [GABRIEL CANIZO]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

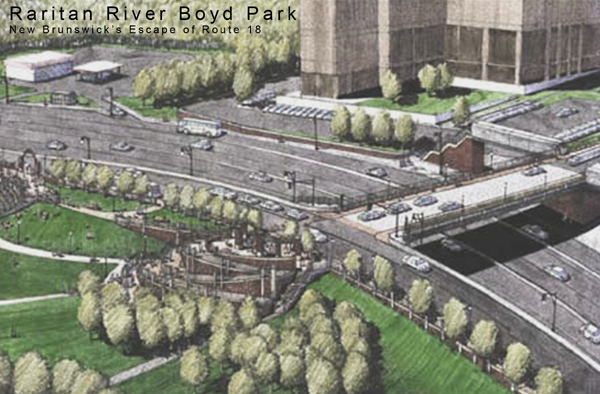

RARITAN RIVER BOYD PARK: New Brunswick’s Escape of Route 18 [JOHN DESOUSA]

New Brunswick, New Jersey, a crossroad city between New York and Pennsylvania that thrived during the 1830s, is incredibly influential and responsible for the majority of central New Jersey development. The city proudly addressed the Raritan River as it was instrumental in emerging the country with large leading industries. Heedlessly, my intention here is not to reflect the riverside implications of the Raritan, but to focus in on a major infrastructural project that constructed the city.

New Brunswick hit a huge commercial decline in the 1960s-70s and the congestion from Route 18, running parallel to the river, made access in and out of the city problematic. To talk about a conscious investigation of New Jersey’s culture of congestion, I turn my focus on the extension of Route 18 and how it manifested into the domains of Boyd Park.

In 1973, local agencies were hired by Johnson & Johnson to address the construction of its new headquarters in New Brunswick. Conclusions led to a series of engineered noise cancelling walls that barracked the city in some areas but in another respect, connected with a series of brick paved overpasses at designated recreational areas of the Raritan. At one scale, that being the connection of Commercial Avenue to Boyd Park, the reconstruction allowed a dramatic drop in grade to set up an amphitheater at the end of a ramped promenade for the cultural arts community and State University to use. At another scale, the improvements included more outer roadways for local traffic, drainage from excessive rainfall that has led to a series of floods from the Raritan, and enhance with extensive landscaping and urban design treatments.

The walls constructed a buffer to existing residential locations and provided safer pedestrian crossings. For centuries, New Brunswick’s riverside environment brought significance to its mobility. At this day and age, the use of engineered infrastructure to protect against flooding is common in cites along the Raritan. Evident enough, Boyd Park at Commercial Avenue’s promenade displays a generic morphology in the discourse of modern development. It was in 1958 that the city claimed Boyd Park would “provide a dramatic setting for vast redeveloping of its most blighted area” (NY Times). Granted, the city’s sensitivity to Route 18’s aesthetics make way for the neighborhood to use. I feel the reconstruction engaged the local residents to make use of the park’s picnic pavilions, boat ramps, and amphitheater.

“Route 18 is an urban principal arterial route that serves the regional and local transportation needs of more than 85,000 vehicles per day” (Dept of Transportation). This highway development is a prime example of New Jersey’s subdivisions. It is evident that the vehicular density come to be of more concern, while its scenic vista took on the task of improving the aesthetics for local pedestrians and bicyclists. New Brunswick’s section of Route 18 stands prominent in the ongoing discussion of New Jersey’s identity. It is to this point that the problematic density of the state is quickly determined by the amount of overpassing outer ways and vast expressways. Boyd Park took light of this trend and decided to engage the cultural community. The two in close proximity make up a diverse vernacular for the nation’s densest state. [JOHN DESOUSA]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

NEWARK: Top to Bottom [NICHOLAS DINGMAN]

One of Newark’s defining features is its business class palimpsest: the adaptation of extant architecture to meet the needs of today’s business leaders. Masterfully executed ornament tops many contemporary storefronts. Such alterations have created an aesthetic dissonance. Bright signs battle with original façade for attention, sometimes occluding significant portions. In some cases, this prevents these buildings from being historically preserved. As a result, opinions on this practice of alteration vary from revulsion to placidity. Should the new tenants vacate in favor of preservation; or should something new be built in the name of progress?

The uneasy visual relationship between the tops and bottoms of these buildings is often overlooked, or considered gross. On the contrary, these relationships speak to the complexities of Newark’s economy and the change in demographics over time. Objectively, each store is fulfilling a need presented by the community of which it is a part.

In an attempt to ignite a discussion about the duality of these conditions, these relationships will be highlighted in two postcards. One pair will be made for each of 6 or 7 quintessentially Newark buildings. Of each pair, one will consist of a dead-pan photograph at street level, and feature text on the reverse describing the historical significance of the building as well as the architectural significance of any ornamentation. The other will be a distorted view of the architecturally significant portion from the sidewalk below, or across. Reverse text will explain how the building is used contemporaneously.

Thus, I hope to invert or distort popular points of view. [NICHOLAS DINGMAN]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

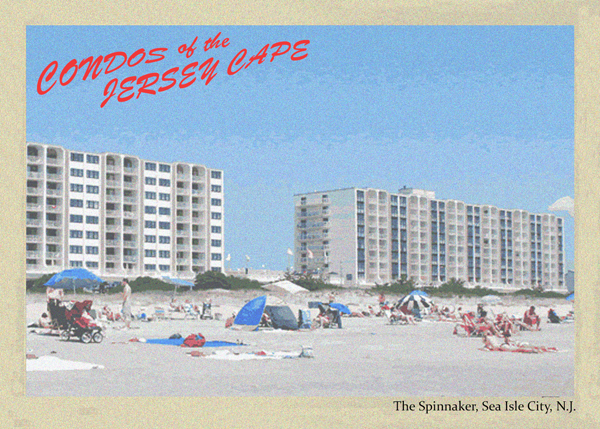

CONDOS OF THE JERSEY CAPE [PAUL FARNAN]

Over time, the architectural vernacular of lodging at the Jersey Cape has changed dramatically. Where resort vacationing began in the United States, seaside accommodations initially existed only within modest boarding houses established by prominent local residents. As larger, wealthier seasonal populations began to arrive, lodging grew to accommodate the shifting demographic and came in the form of grand, illustrious hotels. These hotels were opulently designed to reflect the affluent guests frequenting them during the summer months. The architectural styles of these hotels ranged from Queen Anne, Colonial and Georgian Revival, and Art Deco. Later, following the advent of the affordable automobile and the arrival of a more transient population, motels of the ’50s and ’60s serving motorists became the trend in lodging along the shore. In the Wildwoods, these motels were designed in the Doo-Wop style, which was prevalent during the mid-century period of their construction.

These evolving typologies and varying styles of architecture have come to be renowned as historically significant, each marking particular eras of vacationing along the Jersey Cape. In light of this, some of the most preeminent examples of boarding houses, hotels and motels have been preserved and recognized by designation on both the United States National and the New Jersey State Register of Historic Places.

Today, the growing trend in lodging along the Jersey Cape is the development of condominiums. Condominiums, or condos, are portions of a larger piece of real estate that are individually owned and rented to vacationers, usually on a weekly basis. These buildings are designed in a variety of architectural styles, generally void of any effort toward developing an aesthetic consistent with the given context. The introduction of condos within the built environment along the coast has had tremendous implications on both the nature of vacationing at the shore and its effects on the surrounding environment.

While vacationing at America’s original seaside resorts began as a seasonal escape for some of the country’s wealthiest citizens, over the years lodging along the shore became increasingly available to accommodate visitors of varying social and economic classes. Originally, only the elite could afford to vacation along the Jersey Cape – many of whom were those who initially invested in the region and developed the land that gave rise to these historic resort towns. Now, even those with moderate annual incomes have the opportunity to finance a portion of beachfront real estate. Additionally, the density at which these condominiums are built permits larger numbers of vacationers to occupy and even own a piece of the Jersey Cape.

Like the boarding houses, hotels and motels that were constructed to accommodate visitors of the shore since it was founded as a resort destination, the condominiums of today may too be considered as buildings of historical significance in the future. As architectural historians contended for such designation, similarly, an argument could be made to place these buildings on both the National and State Register of Historic Places. Though some may scoff at the idea, the condo typology can depict almost any architectural style and expression – which may assist or inhibit an argument in the discussion of architectural merit. However, there can be no argument against the fact that the advent of the condominium drastically altered the ownership and inhabitation of beachfront property along the Jersey Cape. [PAUL FARNAN]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

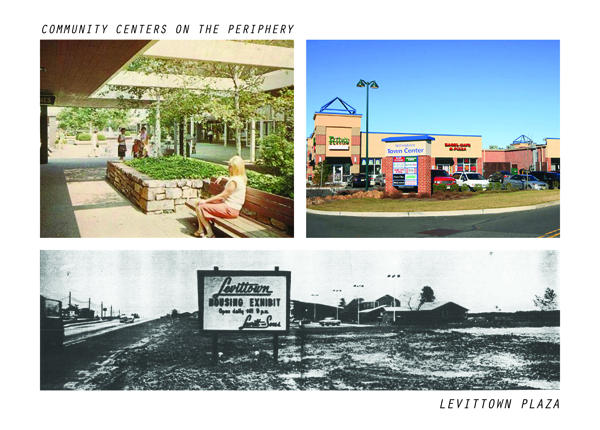

Community Centers on the Periphery: LEVITTOWN REFLECTION [JAMES GIRESI]

New Jersey’s post-war identity is a relentless landscape of sprawling bedroom communities wound together by an extensive infrastructure network. Development of suburbia and the single family unit are highly studied and documented. However, research often stops there, by ignoring the surrounding geography, and other land uses the story of the suburb cannot fully be told. William Levitt’s third venture in New Jersey is used as the lens to uncover the untold story of the retail and commercial landscape and the role these places had in fostering a sense of community in a new strange place. Euclidian zoning and general lack of diversity in land use left the community of Levittown, NJ struggling to develop a cultural and civic gathering space.

Levitt’s commercial venture of the Levittown Plaza had the aspirations to become the regional shopping destination of South Jersey, but the remote location of the community (17 miles North of Philadelphia) and only one highway to get there made the venture risky in its sustainability. Located on the edge of the community, the Levittown Plaza (name changed to Willingboro in 1963) became the gateway to the residential parks. The aspirations of the Plaza becoming a regional destination were quickly hijacked by the community as they grasped for a place that would offer something other than block after block of single family homes. Architecturally the Plaza fostered community, with its open air interior court, but as the demographics of Willingboro changed so did the Plaza. National retailers pulled out as the economic status of the community declined in the 1970’s. New retailers, often Willingboro residents, filled the lack of neighborhood businesses and generally did not have the regional aspirations Levitt designed for.

Deterioration of the Plaza due to lack of income from new retailers and increased crime shifted the communities attention to the development of smaller strip malls within the residential parks of the town. These new strip malls took on the architectural form many know today and the style suited the financial abilities of the new minority population. The sudden proliferation of retail strip malls within the community essentially killed the Plaza. Yet these new retail centers did not have the same success in satisfying the cultural needs of the community. As the area around the once isolated community grew, competition increased made easier by the opening of larger limited access highways within the area. As the area maintained a generally depressed economic climate the remnants of the dead plaza transformed into what originally killed it, the Plaza now known as the Willingboro Town Center is as architecturally un-interesting as any of the many commercial strip malls along the highway. Community identity and investment in retail centers has been lost as the standardization and quantity of retail strips along the periphery continues to sprawl in the same way bedroom communities sprawled in the middle of the 20th century. [JAMES GIRESI]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

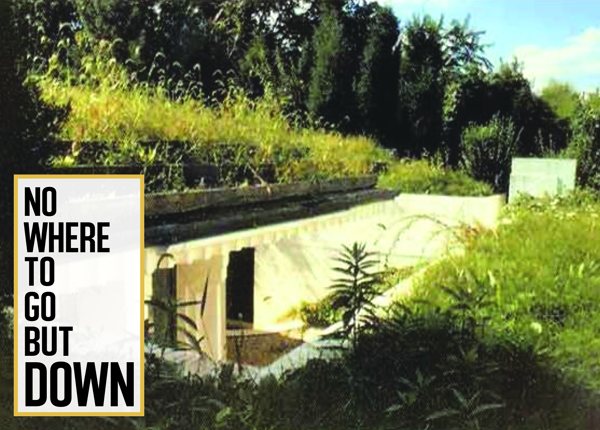

NOWHERE TO GO BUT DOWN: Malcolm Wells in New Jersey [KEVIN McILMAIL]

Malcolm Wells, self-proclaimed “Father of Modern Earth-Sheltered Architecture,” spent over 40 years attempting to convince fellow architects, building professionals and the general public that subterranean architecture was the answer to many of the problems caused by 20th century American suburban development. Duplicitous in his approach, Wells argued that underground architecture was superior to typical for both aesthetic and environmental considerations constantly advocating they be treated as inseparable. While many commissioned Wells to design underground structures, most of these projects were never fully realized due to budget constraints and eventual client disillusionment with the prospect of living in such an atypical environment.

Despite the continued life of Wells’ subterranean work among a select pro-underground following, what has often been neglected by scholars are numerous aboveground buildings he designed throughout his career. In addition to designing several churches, municipal libraries and suburban homes in South Jersey, Wells was the choice architect and draftsman of Camden based electronics company RCA for whom he designed everything from showroom cabinets to entire warehouse research facilities. Receiving commission based on entire programmatic square footage, most RCA projects required only specifying standard details yet provided a critical source of income for a growing firm.

In 1963, after more than a decade of lucrative projects funded by RCA, Cherry Hill architect Malcolm Wells was awarded a commission of any young architect’s dreams: to design the RCA Pavilion for the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, Queens. However, it was not the completion of the RCA pavilion that would have a profound effect on the rest of Wells’ career, but its demolition at the end of 1965, just two years after its completion. The wastefulness associated with pavilion design coupled with the unashamedly commercial and consumer based agenda of the World’s Fair sparked anger in the architect causing him to reevaluate his contribution to these problems. Settling on underground architecture as the solution to these problems, Wells penned an acerbic criticism of the American building industry “Nowhere To Go But Down” for Progressive Architecture in February, 1965.

To limit discussions of Malcolm Wells’ work to only his underground architecture proves problematic when attempting to situate his ideas in a larger architectural, geographical and cultural context. The remaining Wells designs that have not been destroyed of remodeled beyond recognition must be understood as existing within a specific locale: New Jersey. Perhaps it is simultaneously logical and surprising that an architect with a thriving practice in the heart of South Jersey’s rapidly developing and sprawling suburbia (Cherry Hill) advocated for such a drastic reimagining of the urban (suburban) landscape. Those striving to appreciate the entirety of Malcolm Wells’ work must consider it as indelibly connected to New Jersey. Wells’ work remains as much of a celebration of human achievement as it is a criticism of its destructive power, yet this contradiction should not be seen as discrediting; Malcolm Wells’ work should be celebrated as useful metaphor for the greater New Jersey condition. [KEVIN McILMAIL]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

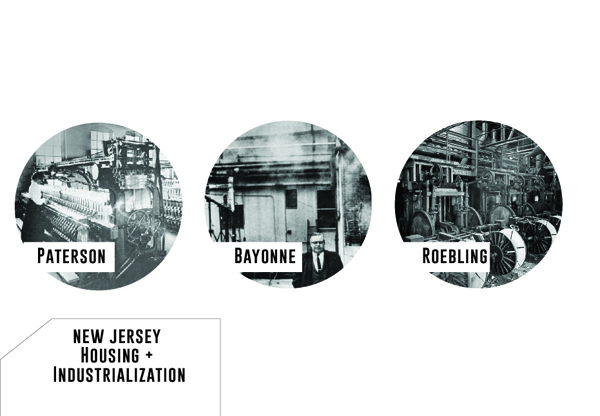

HOUSING DEVELOPMENTS during INDUSTRIALIZATION [LIZZA MEDINA]

Three prominent industrial cities that were researched and analyzed for their housing development during their prime era of industrialization were Paterson, Roebling, and Bayonne. Each city belongs to different fields of production and was evaluated to find that those who were stakeholders in the housing development were specialized industrialists, meaning leaders participating in corporations involved in industrialization or entrepreneurial craftsmen who built their own industrial complex. Ranging from multi-family apartment buildings to semi-detached or single family housing, these cities built these homes by responding to the scale of the city, the population increase, and cost efficiency. By evaluating this research, it relates to the notion of “Delirious New Jersey” by questioning the decisions made of the housing typologies as well as thinking about how to accommodate the employees in terms of living qualities and their relationship to the industrial complexes.

Paterson, the “Silk City,” became a prominent city that specialized in the production of the textiles and locomotive manufacturing in the latter half of the 1800’s and emerged along the Passaic River due to the use of the Great Falls for power. Supporting a population that started at 11,000 in 1850 to 106,171 in 1900, The Society for Establishing Useful Manufacturers (SUM) built housing developments that were placed in close proximity to the factories in two to three-story high detached houses that were wood framed with flat facades on brownstone foundations to accommodate the lifestyle of a worker of one of the mills.

Bayonne, as the leader of oil refineries during to the 1920’s, The Bayonne Housing Corporation established the Garden Apartment as the main type of residence for the worker who was employed in the large complex along the Newark Bay. Due to the substantial increase of population and lack of available land, the garden apartment was suitable to rethink the living conditions for their workers and provide units that will suit 150 families in 5 to 6 bedroom apartments. Like Paterson, these apartments are wood framed and constructed with brick for cost efficiency and to create a link to the construction of the oil refineries as well.

Roebling, known for the production of wire rope underneath the supervision of Charles A. Roebling, created a hierarchal arrangement for their housing and developed different types of typologies that suited the skills of their workers. Having the city arranged in a checkerboard pattern, head managers were living in single family homes close by the Delaware River, while hourly workers lived in rowhouses in close proximity to the wire rope plant. Each house was also built in brick and framed construction.

The research that covered these industrial cities and housing developments relate to Delirious New Jersey in the notion of how the influx of immigration and the emergence of factories were handled by accommodating the workers in different types of housing typologies. Along with the similarity of having industrialists as developers, they used the same criteria to accommodate the lifestyle for their workers while keeping them close to their occupation. Therefore, we can understand why and how the origins of these housing developments emerged in the typology that they are. [LIZZA MEDINA]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

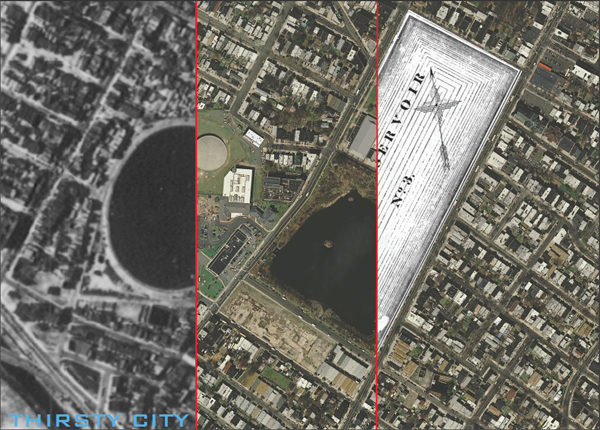

MONUMENTS of a THIRSTY CITY [MARK RUSINSKI]

Jersey City’s water supply has been changed and been manipulated from the early 1800’s when the residents water came from wells, springs, public pumps and even brought to residents door to door. The building of the reservoirs would allow Jersey City to grow as stated in the 1911 Jersey journal article issued by the Publicity Committee of the Jersey City Board of Trade labeled Its Superb Advantaged as a manufacturing and Business Center and Place of Residence.

The reservoirs are labeled incorrectly reservoir number one is actually the reservoir that is labeled reservoir one or Bergen Hill reservoir. This reservoir was the first built and was to be part of a larger complex of reservoirs, three in total. Reservoir Number two however was never built and now serves as a park, Pershing Field. The park being built in 1922 long after the last and fourth reservoir was built in Boonton, or over Boone-Town which meant that not only did the city want a cleaner water source but also needed more water than if all the reservoirs were built. The Boonton reservoir was completed by 1904 providing clean water to Jersey City. Boonetown at the time was small village 23 miles above Jersey City in a deep valley that was always flooding. The last residents of the village were some farms an orphanage and the Morris County Poorhouse. It is said that you can see the shadows of the buildings in the water.

Reservoir number one is no longer in existence but is on the historic register of sites for what may be beneath the site and reservoir number three is also a historic site that is being turned into a park which residents can enjoy and is open to the public for fishing and eventually rehabbed. The reservoir walls, gatehouse and remaining waterworks building that still remain are monuments to Jersey Cities growth. Although the reservoir does not serve its original purpose it will still serve the community as soft infrastructure.

These reservoirs show us how New Jerseys hard infrastructure in a densely populated state needs to either serve double duty as hard and soft infrastructure as the Boonton Reservoir or be repurposed. Maps of the area show how Jersey City and New Jersey has changed. New Jersey is in constant change and adapting itself to provide for its inhabitants.

I have focused on the Jersey City water system but this same situations have happened in other cities in New Jersey. Though maps and photos we can explore the infrastructure that has provided and will keep providing for Jersey City and one of the main reasons that they can do that is because they were built to last and have good bones which have allowed them to survive and has given them a certain appeal to be preserved, saving this piece of history to enjoy. [MARK RUSINSKI]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

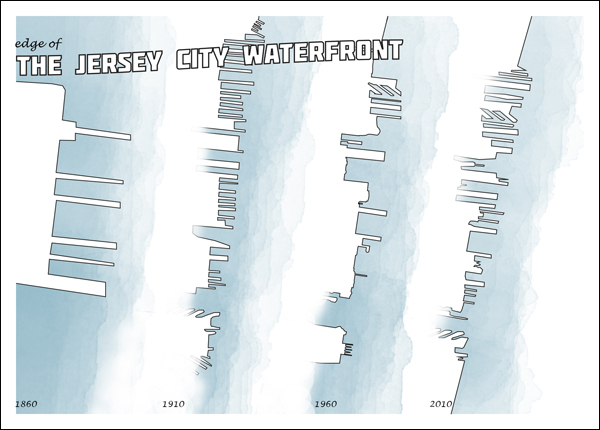

EDGE of the Jersey City Waterfront [LARA SALEH]

The research presented here serves to analyze the dynamic edge of the second largest city in New Jersey, Jersey City located in Hudson County, with a concentration on the Jersey City Waterfront. Historical maps were utilized and analyzed to graphically represent the development of the Jersey City Waterfront edge over four time periods (1860, 1910, 1960 & 2010) paying close attention to the shift in land use, scale and spatial development.

Although the research was limited due to available sources, it is clear that the edge of the Jersey City Waterfront was informed by the ever-changing needs of a developing society. In 1860, the current waterfront was a mere tidal pool lined with manufacturing plants on mega blocks that used the Hudson River as a dumping ground. By 1910, the city grid was broken down into smaller blocks and the tidal pool is filled to allow for more water “frontage.” Essentially, with the growing needs of the manufacturing industry, transportation and commerce demands increased, leading to a transportation hub to develop along the waterfront. By 1960, the manufacturing industries began to move over seas leaving grey-fields and ‘patchy’ development along the waterfront. Additionally, some of the abandoned warehouses transitioned to low-income housing. Presently, all the low-income housing is relocated along I-78 to allow for high-rise luxury apartments to populate the waterfront. The previous wasteland is now in high demand with dense streets and even denser vertical and horizontal development along the Jersey City Waterfront.

Essentially, this research serves to document the changing edge of the waterfront and analyze the different factors that contributed to such a change. The Jersey City Waterfront is undeniably an enduring transportation hub with fluctuating transportation systems, scales of development and land-use. [LARA SALEH]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

I-78 Interstate Habitation [CHARLES SANCHEZ]

The idea of converting a non-living space into a habitable space can be an interesting topic that many architects and cities would benefit from focusing on. Once all the land of New Jersey is used, we as architects should start looking for alternatives on where to create new built environments, even in those places that have no program or planning. This survey documents observations on the potential for use of elevated highways. These areas have much potential to accommodate both to a variety of activities and creating shelter. New Jersey has been growing horizontally, creating a build up of congestion, density and spread. Interstate I-78, passes through Jersey City, touching the site very lightly and without any physical disturbance between the east and the west part of Jersey City. There is an elevated portion of the freeway that runs about two miles and acts as a barrier that separates Jersey City into two different environments. The space underneath this portion is being filled with parking, summer gardening, sport activities, civic gatherings, housing for electrical wires, and many other valuable conditions that help reshape the negative connotation of the dead space under an elevated freeway. Associated with crime, defacing and vagrant populations, these areas offer a space that instead could be used as a benefit to the city.

Furthermore, this research serves for observing the potential of these spaces for future and current use. Different conditions ranging from parking to sport activities creates an environment that perceived positively and is a case study on how to use congested landscapes that were unplanned or in need for new development. Residents of Jersey City used to look at Interstate I-78 as a negative impact within the city. However, this is changing because of the recreation, the new usage, and the significant activities that are taking place underneath I-78. These activities are also helping reshape the disconnection that the elevated freeway created when it was first built in 1963. Positive conditions are being created from these voids. Where public opinion had reacted negatively to this space before, it is now changing to a positive perception. Some of the positive aspects found during the documenting of what is happening underneath I-78 in Jersey City, is the result of the freeway’s great infrastructure creating opportunities. Not only sheltering from the sun, but residents in the surrounding area utilize the space underneath as community garden, spaces for parking, and to allow children to be protected from street traffic while playing sport activities. In addition to the existing condition, it is obvious that these spaces are becoming part of our daily interaction of the built environment and impacting us in a positive way. After looking at the possibilities for recreation and activities that are taking place underneath Interstates I-78, it is very apparent to me that this infrastructure is connecting back the community together because of its current space usage. Also it is merging back the urban fabric of Jersey City because community activities and other significant changes are taking place here, serving as the connecting point between the east and the west. Lastly, the current and potential usage of space underneath I-78 in Jersey City is transforming and generating a new idea of how we can occupy spaces that did not have much civic value in the past. [CHARLES SANCHEZ]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

NJ RAIL PALIMPSEST [NICHOLAS VICINIO]

New Jersey’s density patterns can best be represented by understanding the current state of the railroads, and its previous functions. The multitude of functions seen when examining rail lines of New Jersey today, are directly related to settlement patterns in the state and the mobility of the populace. While some lines have retained their existence as a heavy rail line, others have switched over into different owners over time, each one using the corridors for their own, unique purposes. The overlaying of those various layers creates a palimpsest which is representative of New Jersey itself.

From horse drawn trains to electric powered trains, all railroads across the state have seen the integration of iron tracks into the ground. They either connected factories to natural resources or people with jobs. Passenger trains were seen far and wide as the best and most economical means to get around the state. While that view changed with the advent of the automobile, reality kicked in after World War II, and in 1959, the first of many rail lines became abandoned. This was also true for freight rail lines, but much sooner, which was after the Great Depression. The rail lines that became vacant never rekindled their primary functions, and that is what can be read across the state today.

Their disuse not only tells one that people started taking other means of competing transportation, such as bus and private car, but also that the New jersey economy started to depend less on these time-honored means of transit. Over time, jobs moved into office parks miles away from train stations along newly developed and expanded highways for the automobile; quaint retail stores in downtown areas moved into strip malls; and people moved out of high density areas in search of greener pastures with larger lot sizes. This horizontal shift of the New Jersey lifestyle has left once prosperous rail towns into municipalities clinging for life, with crumbling economies due to a large loss of tax revenue.

Some of those areas that lost their heavy rail, in recent years, have sought out ways to repurpose the lines to make them usable to residents once again; and ultimately, improve housing values, connectivity, and the economy at large. At a smaller scale, two railroads have resurfaced as light rail lines. The introduction of this type of service in recent years is reflecting a changing demographic where there are more enclaves of small lot size and high density, leading to the feasibility of such a system.

At the other end of the spectrum, areas that have low density have also sought to reinvigorate its rail corridors. Through grassroots and local efforts, lines in those areas have been stripped of iron and replaced with pavement through Rails to Trails, allowing for a park like corridor for biking and walking. While much of the state is built out, these areas allow for a greater chance for the people of New Jersey to connect with nature. That palimpsest has added to the hotbed of sustainability in the state by decreasing dependency on the car and increasing park space. [NICHOLAS VICINIO]

Invalid Displayed Gallery

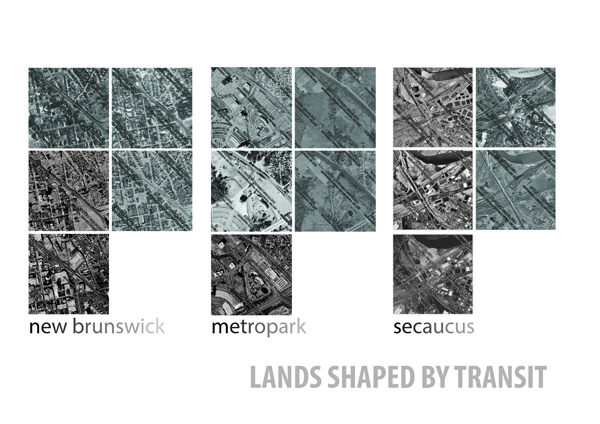

URBAN STRAND OF TRAINS [GRETCHEN VON KOENIG]

In a state where the land where builds spread out, and not up, how does the New Jersey train program add to the planning of the state, the city, and the areas that it runs through. Looking at Secaucus, New Brunswick and Metropark as case studies, I hope to find evidence of how the train influenced the horizontality of New Jersey by way of density and infrastructure. Due to it’s alarming density of population and infrastructure but civically orbits around New York and Philadelphia, New Jersey faces perceptional disconnects of urban statuses vs. rural dwellings. Given its abundant resources and geographical advantages, it was early identified as a benefactor to both New York City and Philadelphia. In doing so, New Jersey’s places spiraled into what would be known as the “The Megalopolis”. In the book, “Megalopolis”, sociologist Jean Gottman states “Every city in this region spreads out far and wide around its original nucleus; it grows amidst an irregularly colloidal mixture of rural and suburban landscapes” (Gottman 5) Certainly, New Jersey’s dense population, the densest in all America, suggests that in fact, New Jersey is a long string of urban places to make up the Megalopolis, and not the suburb that it’s acts to it’s orbiting cities. How do the trains add to or detract from this? Do the train stations influence city planning? While it may be a natural course of logic that development follows train station stops because of easy commuting, as found in Metropark, it spurred little to no development in a place like Secaucus, even when there was an intentional plan to do so.

Furthermore, through the study of the build up around these specific train stations, I would like to analyze if town planning around the train stops services to the social and economical orbit of New York/Philadelphia or if it services to New Jersey. Given that I can’t fully examine the socio-economic under pinning’s of these three areas, it was rather hard to deduce. I have however found that the infrastructure in city areas like New Brunswick, provided areas that seem to service itself, as it was a destination outside the train. Contrastingly, Metropark’s building development services the train and the idea of commuting. It does not promote Iselin for the immediate surrounding area as a place, but rather as just a stopping point during the day. And on the other extreme, Secaucus completely serves to the orbit of NYC, addressing no civic areas and only the train station. Gottman talks of the non-distinctions between rural and urban in the region of the megalopolis, claiming that these areas “function largely as suburbs in the orbit of some city’s downtown” and that “traditional notions of urban and suburban do not apply here”. Secaucus services people that would be clearly addressed as urban, but it’s infrastructure suggests suburban. Applying this theoretical viewpoint, I examined places that lay on the Northeast Corridor Train in order to deduce if the classifications of urban do or do not apply. The Northeast Corridor accounts for NEC riders account for 69 percent of the combined airline and rail market between Washington, DC and New York City and 51 percent between New York and Boston (NEC Future). Specifically looking at New Brunswick, Metro park, and Secaucus, these stops provided varying conditions and considerations that lend themselves to a larger metropolitan area, the immediate surrounding area, or a mixture of both to analyze under the conditions of the “Megalopolis” and the horizontality as it effects the built environment. [GRETCHEN VON KOENIG]

Invalid Displayed Gallery