The Hut, part i 15 March 2011

After a gap of many years I recently returned to teaching the origins of architecture in an undergraduate history survey. I still call this course “caves to cathedral,” but I don’t actually begin with caves. In fact, my first lecture starts with the Seagram Building, but I’m still considering a new nickname: “hut to Bauhütte.” The alliteration may not be as satisfying as in “caves to cathedrals,” but it gives the hut pride of place.

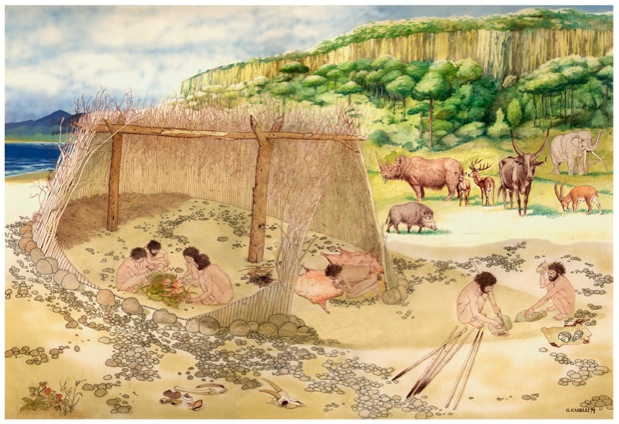

Around 300,000 BCE Paleolithic homo erectus returns each spring to the same spot in the south of France, near Nice. There, homo erectus builds a hut from palisaded branches and bark, securing the foundation with rocks. The hut is severely furnished: a sleeping area, a work area, and a hearth are all that are needed to satisfy the mobile lifestyle of the Paleolithic period. Henry de Lumley, the archeologist who discovers the encampment, calls the site terra amata, or beloved earth, perhaps acknowledging that the original hunter-gatherer foresaw the marketing potential of the Mediterranean. Though archeologists have since argued that Lumley’s enthusiasms overwhelmed his empiricism, “la hutte terra amata” is still regarded as one of the earliest human-made habitations.

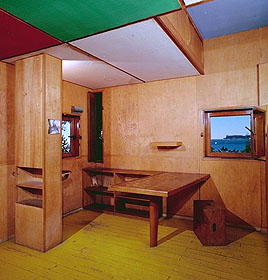

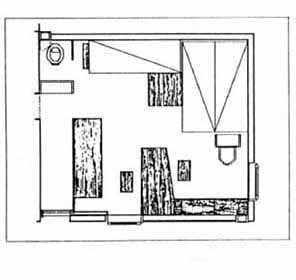

Awhile later, in 1952, and not far away, at Roquebrune-Cap Martin, Le Corbusier builds a hut for himself as a final retreat at the end of his life. Like the prehistoric visitors who preceded him, Corbu returns each spring, until his death in 1965, to a petit cabanon, a 12’ x 12’ square, wood-framed and lined in plywood. The cabanon was originally to be clad in sheet metal, a modest exercise in machine age modernism that recalls the architect’s early fascination with the automobile and the train compartment as models for machines à habiter. At the last minute Corbu substitutes split logs for the exterior and, thus, transforms his cabanon’s architectural aesthetic. Now, the cabanon reflects the brutalism Corbu prefers in his later career, along with his disenchantment with the industrial age, its waste, its pollution, its material excess.

The existenzminimum of the cabanon’s interior includes a precisely arranged toilet, table, cupboard, and bed. The arrangement owes less to the economy and simplicity of the assembly-line mass production that inspired the radical architect Corbusier once was than to the economy and simplicity of the 18th and 19th century philosophical traditions that inspired the romantic dreamer he never ceased to be. These are just musings. For a full description see Deborah Gans’ excellent Le Corbusier Guide.

Next: Huts in the Land of Lincoln.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.