Thoughts on the Black Box 2 April 2019 No Comments

I approached the task of responding to a paper session on conventions of research in architectural education by following the prompt of the session’s co-chairs, and returning to the thing itself, to the “black box” that the conference organizers used as a starting point for the theme of the 107th annual meeting of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture.

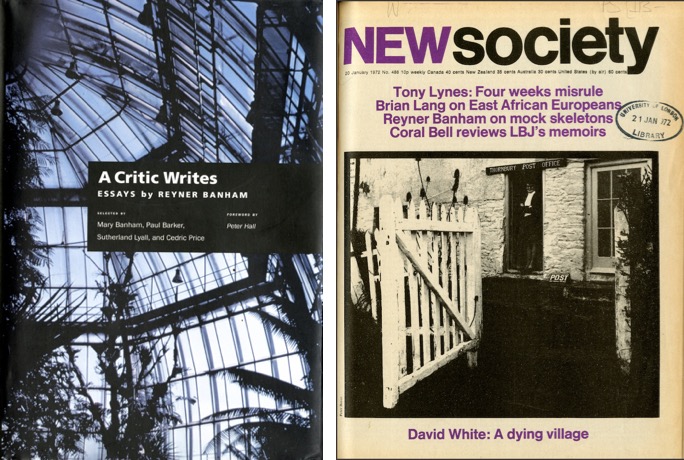

Reyner Banham wrote this eponymous essay (“A Black Box: The Secret Profession of Architecture”) on his deathbed in 1988, black ink on a yellow legal pad in a surprisingly steady hand for a guy already hooked up to life support (the original manuscript is preserved with his papers at the Getty Research Institute). And what was he contemplating as he penned what would be the last of the more than 700 essays he wrote in a four decade career? The secret profession of architecture.

Most of us likely know this essay because it was reprinted in the Banham anthology A Critic Writes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), a book probably not much read by anyone outside the spheres of architecture and design. But as with so much of Banham’s critical, as opposed to historical writing, this essay was likely intended for a much larger audience, and it was published (posthumously in 1990), in the New Statesman and Society (12 October 1990, pp. 22-25). This was the journal of social inquiry and cultural critique aimed at the so-called “new intelligentsia” in which Banham had published much of his freelance journalism. This is important because, as Banham himself acknowledged, he wrote in different ways for different audiences, and it is fair to say that the less specialized the readership, the greater the snark.

“Black Box” contains some of Banham’s most memorable turns of phrase. To give you two examples: postmodernism, in its reliance on the erudition implicit in borrowing the formal elements of historical eclecticism, had “the same relation to architecture as female impersonation to femininity.” It was not architecture, but “building in drag.” In taking Nikolaus Pevsner to task for what Banham regards as Pevsner’s “academic snobbery” in making a pernicious (if famous) distinction between the Lincoln Cathedral as “architecture” with a capital A and a bicycle shed as mere building (in An Outline of European Architecture, 1963), Banham argues that Pevsner makes “a supposition about sheds that is so sweeping as to be almost racist.” Obviously, Banham’s privileged position as a white cisgendered Englishman enabled his casual use of drag and race as literary devices. But it’s still damn good writing, this use of highly evocative language from outside of architecture to explain architecture to those who are not necessarily architects.

I do not want to imply that “Black Box” was in any way intended as satire, but a careful reading of the essay suggests that Banham—even as he carefully unpacks differences between various modes of designing and building—was utterly uninterested in reifying a disciplinary core for architecture. Indeed, the essay ends on a note that sounds cautionary or ironic depending on your perspective. The “tribe of architecture,” Banham observed in 1988, was well within its rights “to defend the contents of the black box at whatever cost, as if it were the ark of its covenant.” (NB: Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark was released in 1981.)

And Banham forcefully articulated what was at stake in what he called “the threat of ultimate revelation.” If the tribe of architecture revealed itself “to the understandings of the profane and the vulgar”— making architecture comprehensible to everyone outside the elitist domains of the profession and the academy—it ran the risk of “destroying itself as an art in the process.” But the alternative was equally fraught: if the tribe remained, in effect, a secret society, contentedly cloaked in own exceptionalism, it would, inevitably, be regarded with distrust and apprehension, “perpetually open to the suspicion,” Banham argued, that the black box contained nothing at all beyond “a mystery for its own sake.”

For Banham writing in the late eighties, it mattered little whether the profession and the academy were in the throes of modernism or postmodernism, because the discourse of both amounted to what Banham described as a “secret value system”—one that was equally and deliberately inscrutable to those outside the tribe of architecture. From modernism to postmodernism, and on through deconstructivism, the parametric moment, the digital turn and so on and so forth until the present day.

But thirty years on (from when he penned the essay), we can see even more clearly something that Banham was only beginning to discern—and that, if you’ll indulge one more Raiders of the Lost Ark reference, is the potential for the utter irrelevance of the black box and all the secrets it might contain—packed up in a metaphorical crate, lost in a theoretical warehouse.

But let’s imagine a different scenario for that black box, a scenario in which the black box is not so much dismantled, but replaced it with something far less opaque, something that probes the tensions between the normative and the exceptional in architecture, and in pedagogy, by making their operation explicit. In contemporary software development, this is the difference between black box testing (in which the internal structure, operation and contents remain UNKNOWN and OPAQUE to the user) and white box testing (in which everything is fully revealed to the user).

While Banham’s “Black Box” acknowledges the existence of the computer and its potential impact on architecture, in 1988 it was too early in the information age for him to really comprehend the transformations at hand. And in my reading his “recognized by its output” black box seems more akin to eighties-era high-tech hi-fi, which positively luxuriated in the matte black boxiness.

This doesn’t mean we can’t give him the last word (or trope)–even if we risk anachronism. Given Banham’s well known—and even immoderate—techno-philia what metaphor he would have chosen to replace “the black box” in our cyber-spatial age?

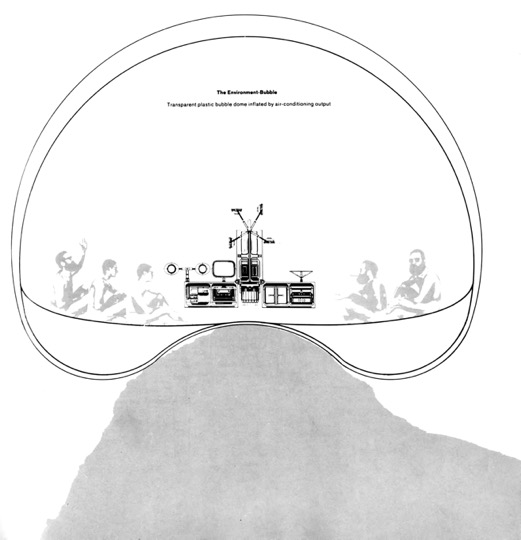

I’ll end by suggesting this one: François Dallegret’s illustration of the “environment-bubble,” drawn to accompany Banham’s “A Home is Not a House” essay (Art in America, April 1965), depicts a transparent, inflatable bubble-of-a-building. Inside this inflated membrane, is Banham himself. Naked but for sunglasses and full beard, he sits before a high-tech pile that resembles nothing so much as the guts of the black box itself. The essay has nothing to do with the secret profession of architecture and everything to do with the energy inefficiencies of the typical midcentury suburban American house.

Nonetheless, the image is relevant to the question at hand. Not because it aptly illustrates what a cynic might regard as architecture’s over-exposure in the twenty-first century, but because it usefully illustrates a possible future for architecture’s disciplinary core in the twenty-first century, willfully even brazenly displaying its contents because architecture has, in effect, nothing to hide. By replacing the black box, architecture—in its production, pedagogy, and research—might finally be able to reverse its disciplinary inward gaze. In a clear bubble you can see forever.

Finding North Asbury 7 January 2019 No Comments

After running some errands last week, we took a different route home, not too far afield, but just far enough to engage in some urban exploration of the psycho-geographical sort. Call it drifting down the shore. And that’s how we found this happy vestige of North Asbury Drug, a horizontal neon sign in silhouette along the roof of a rundown one-story back building with a larger sign painted on the wall just below.

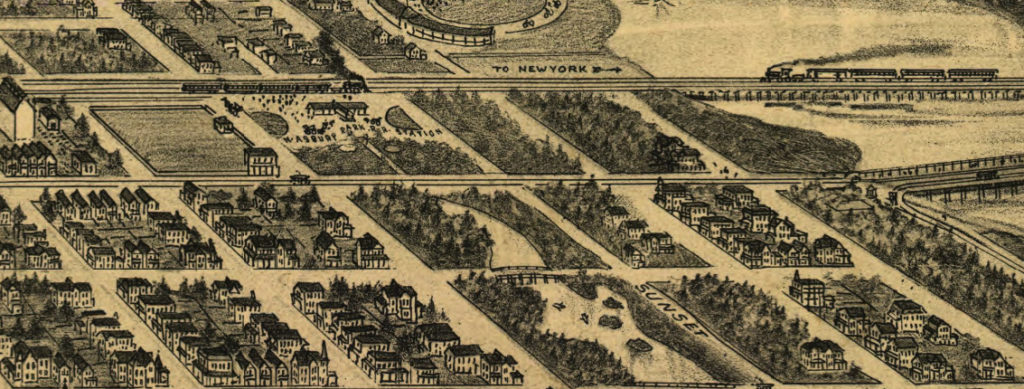

“North Asbury” is no longer an official designation, but it still refers to that part of town north of Sunset Park between the ocean and the railroad tracks. At one time North Asbury also identified a train station.

In the 1890s, the New York and Long Branch Railroad erected the canopied building that still stands on the east side of Memorial Drive. In the 1950s, the railroad leased part of the station building to the Asbury Park National Bank for a branch office, complete with drive-in tellers. By then, the New York Times described North Asbury as a “growing residential section,” one that supported not only regular train service, but also a small commercial crossroads running along the block of Fifth Avenue just south of the station, which served as a kind of anchor.

North Asbury Drug was one of the corridor’s thriving midcentury establishments. It advertised regularly in the local paper and it fielded a winning basketball team in the local league. When the trains stopped calling at North Asbury station in 1975, North Asbury Drug was still in business, probably under the proprietorship of Howard Stuart Isaacs (1945-2016). Though it retains a spectral presence on the web, as a physical store North Asbury Drug is long-shuttered, and the space it once occupied is now a community health center.

That storefront and a handful of others on the block are what remain of the North Asbury commercial district. The street-level retail offers a snapshot of Asbury Park in the second decade of the 21st century: a gay bar, a barbershop, a falafel take-out place. The building as a whole has suffered numerous indignities, most egregiously in the tin siding covering the projecting bays and ornamental cornices. The storefronts are equally compromised in terms of material and design, but all of them, albeit modestly, evidence pride of place in their signs and window lettering.

As for the last vestiges of North Asbury Drug, that old sign still makes an impression, with its rusted, but still upright channel letters and even a few glass tubes still in place. What color was the neon? Was the sign visible to passing trains? (It runs parallel to the tracks, a few feet away.) Of course, in 2019, in a town in transition, the real question might be, how long before an enterprising urban scavenger removes the sign for resale in a vintage boutique downtown?

November 8th, 2016 14 November 2016 No Comments

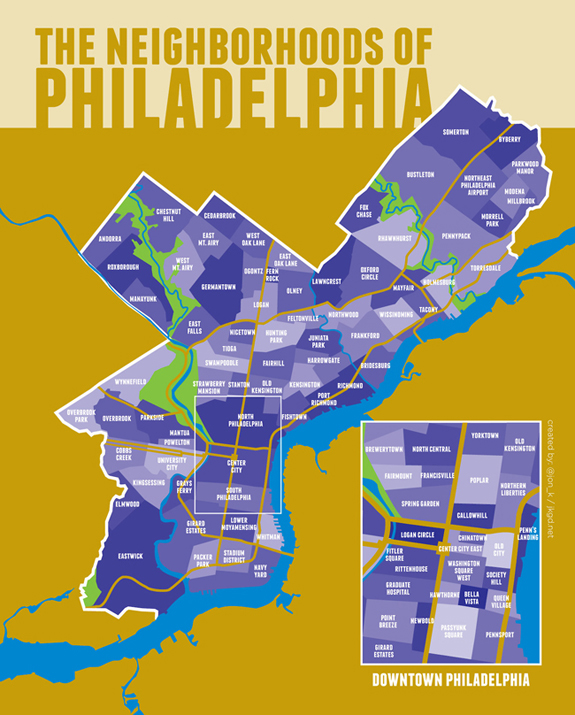

As we travelled slowly southeast along Germantown Avenue, areas of long-standing prosperity gave way to expanded fields of gentrification, which gave way to districts of just barely hanging on marginality, which finally, and monumentally, gave way to the wide variegated swath of impoverishment and abandonment of North Philadelphia (as in north of Center City). North Philly is not one single place; it’s made up of distinct neighborhoods, all of them shaped as much by social and economic evolution as by physical geography.

As we travelled slowly southeast along Germantown Avenue, areas of long-standing prosperity gave way to expanded fields of gentrification, which gave way to districts of just barely hanging on marginality, which finally, and monumentally, gave way to the wide variegated swath of impoverishment and abandonment of North Philadelphia (as in north of Center City). North Philly is not one single place; it’s made up of distinct neighborhoods, all of them shaped as much by social and economic evolution as by physical geography.

Annexed into the city in the 1850s, North Philadelphia became a center of industry in subsequent decades. By the turn of the last century, much of its gridded extent was densely built with blocks of row houses, mostly two stories, and with considerable typological variety. Blocks of red brick houses are followed by blocks of buff brick houses. One side of the street has projecting bays and porches; the other side has flat fronts and stoops. Some blocks have elaborate cornices; others have decorative columns.

My mother grew up in one of those North Philly row houses near 27th and Allegheny (that’s her on the stoop in 1953), on a street where the block’s original homogeneity was long ago replaced by idiosyncratic individualizations that accumulated over the decades: tin siding, vinyl siding, asphalt siding, awnings, astroturf, and so on (as is clear in the google street view). My grandfather made his own contribution when he added a railing and milk bottle holder to his Etting Street stoop, thus preventing members of his family from posing in that spot for any subsequent photographs they might have taken before my grandmother sold the house and moved in with us in 1974.

My mother grew up in one of those North Philly row houses near 27th and Allegheny (that’s her on the stoop in 1953), on a street where the block’s original homogeneity was long ago replaced by idiosyncratic individualizations that accumulated over the decades: tin siding, vinyl siding, asphalt siding, awnings, astroturf, and so on (as is clear in the google street view). My grandfather made his own contribution when he added a railing and milk bottle holder to his Etting Street stoop, thus preventing members of his family from posing in that spot for any subsequent photographs they might have taken before my grandmother sold the house and moved in with us in 1974.

While we might look for meaning in these individual physical markers, it’s their aggregation across North Philly that creates the strongest impression of the changes that have taken place here in the last half century, as factory closings, block busting, absentee landlordism, and generational poverty left their mark on these row house blocks in predictable and devastating ways. North Philadelphia today is less the “inner city” of political dog whistles than “the Ghetto” in the complex, even classical sense that Princeton sociologist Mitchell Duneier lays out in his important recent survey, Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea. As we drove across North Philly on ElectionDay, an extended landscape of urban decline seemed to stretch out in every direction, revealing itself with numbing effect as we passed block after block of empty shells, boarded up buildings, and run-down row houses.

But we weren’t just passing through that day, and any deadened detachment we might have been feeling ended each time we pulled up to a particular house to pick up the specific North Philadelphian residing at that address and in need of a ride to the polls. A few of our fellow citizens needed rides because they had mobility issues, but more of our fellow citizens needed rides because they were registered to vote in election districts far away from their current places of residence. A few of our fellow citizens had missed the deadline to change their registrations, but more of our fellow citizens were contending with the realities of housing displacement that the economically insecure live with every day. Some of our fellow citizens couldn’t afford to pay the fare for the multiple subways and buses they’d have needed to take to their polling place–and it didn’t help that the recently-settled SEPTA strike had screwed up their weekly passes. Some of our fellow citizens couldn’t afford the time such a journey would take–we drove one young woman nearly 14 miles across town. But every one of our fellow citizens was determined to exercise the franchise and vote in the 2016 presidential election, and it was a patriotic privilege to help them make this happen just by getting behind the wheel with a smartphone.

It was long past dark and after 7:30 when we pulled up at our final polling place, a public recreation center in North Philadelphia, in a row house neighborhood not far from Temple University. The line to get inside snaked across the playing field and out onto the sidewalk, but since poll workers had assured everyone that if they were on the line before the polls closed at 8 pm they would be able to vote, the mood was more festive than restive. As we stood there with the crowd (because our voter also needed us to drive her home from the polling place), it seemed like the anxiety of the previous months was being slowly washed away, not by a certainty of victory, but by the mere presence of our fellow Americans waiting to vote in the City of Brotherly Love.

It was long past dark and after 7:30 when we pulled up at our final polling place, a public recreation center in North Philadelphia, in a row house neighborhood not far from Temple University. The line to get inside snaked across the playing field and out onto the sidewalk, but since poll workers had assured everyone that if they were on the line before the polls closed at 8 pm they would be able to vote, the mood was more festive than restive. As we stood there with the crowd (because our voter also needed us to drive her home from the polling place), it seemed like the anxiety of the previous months was being slowly washed away, not by a certainty of victory, but by the mere presence of our fellow Americans waiting to vote in the City of Brotherly Love.

Speculations on the Origins of the Jersey City; or, Geographies of Drinking, cont’d. 21 February 2015 No Comments

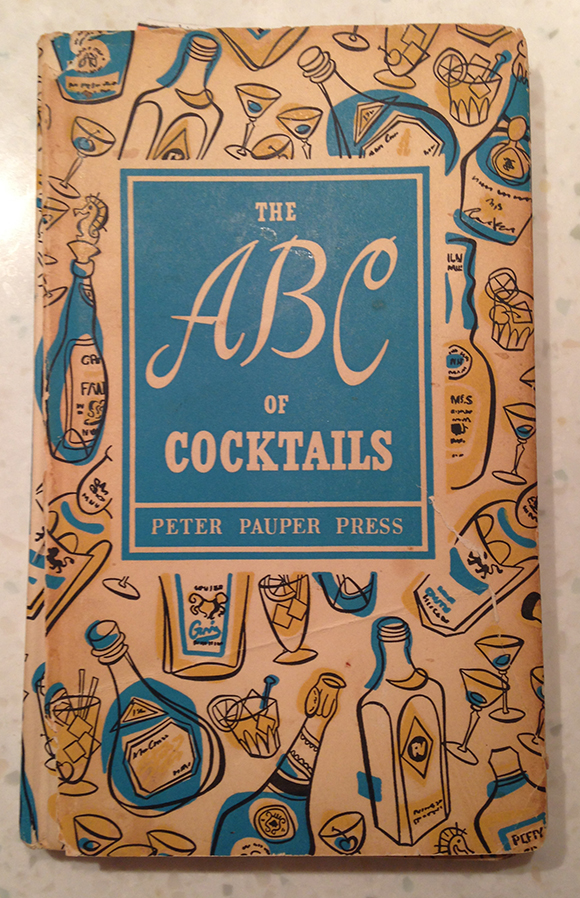

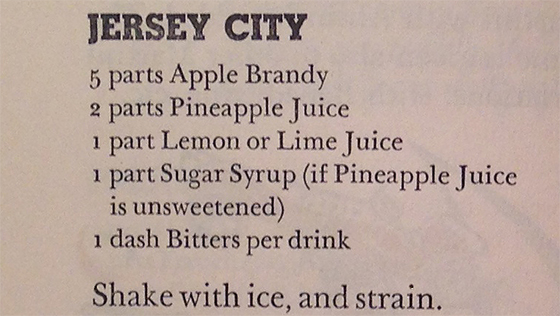

Some months back, I chanced upon an unfamiliar book on a shelf in my parent’s kitchen: a little volume on cocktails that was jazzier than the venerable Mr. Boston (the book to the left) and less learned than William Grimes’ Straight Up or On the Rocks (the book to the right). Published by Peter Pauper Press in 1953, The ABC of Cocktails was part of an extended series of whimsical, food-oriented primers edited by Edna Beilenson and illustrated by Ruth McCrea (and now reissued in kindle editions). Though filled with lightweight rhymes (“Alcohol’s a temptress, alcohol’s a flirt, She’ll either raise you to the skies, Or drop you to the dirt.”), the recipes were intended for “experienced drinkers,” rather than “amateurs [and] maiden aunts.” Being an experienced drinker myself, I gave The ABC serious consideration. The cocktails it included went well beyond the standard repertoire, even that of our expansive updated-classics era: Ward Eight, High Hat, Third Rail. But what really caught my eye, vis-a-vis a broadening interest in the nexus of geography and spirits, was an impressive number of drinks with place-based names. Not just usual suspects like Manhattan and the Bronx, but Hong Kong, Havana, Kingston, Monte Carlo, Nevada, and Florida. Of these eponymous drinks, one in particular stood out.

Some months back, I chanced upon an unfamiliar book on a shelf in my parent’s kitchen: a little volume on cocktails that was jazzier than the venerable Mr. Boston (the book to the left) and less learned than William Grimes’ Straight Up or On the Rocks (the book to the right). Published by Peter Pauper Press in 1953, The ABC of Cocktails was part of an extended series of whimsical, food-oriented primers edited by Edna Beilenson and illustrated by Ruth McCrea (and now reissued in kindle editions). Though filled with lightweight rhymes (“Alcohol’s a temptress, alcohol’s a flirt, She’ll either raise you to the skies, Or drop you to the dirt.”), the recipes were intended for “experienced drinkers,” rather than “amateurs [and] maiden aunts.” Being an experienced drinker myself, I gave The ABC serious consideration. The cocktails it included went well beyond the standard repertoire, even that of our expansive updated-classics era: Ward Eight, High Hat, Third Rail. But what really caught my eye, vis-a-vis a broadening interest in the nexus of geography and spirits, was an impressive number of drinks with place-based names. Not just usual suspects like Manhattan and the Bronx, but Hong Kong, Havana, Kingston, Monte Carlo, Nevada, and Florida. Of these eponymous drinks, one in particular stood out.

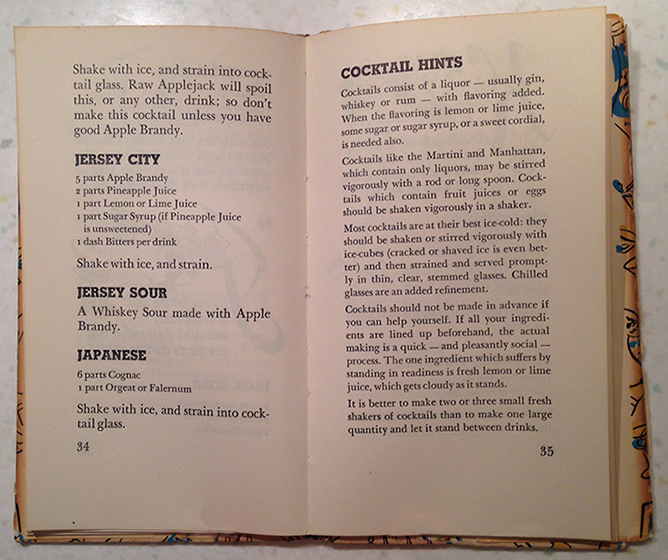

The Jersey City appears on page 34, in between the Jack Rose (immortalized in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises) and the Jersey Sour. Like both of those drinks, the key ingredient in the Jersey City is apple brandy, a.k.a. applejack. As noted in an earlier discussion of the Newark cocktail, applejack can rightly be considered the state spirit of the Garden State, having been produced in Jersey since shortly after the first European settlers arrived. Though grains don’t grow well in New Jersey, fruit trees do; apples, in particular, have been called the foundation of the state’s “fruit culture.” It goes without saying that in the 17th and 18th centuries, folks were drinking those apples as frequently as they were eating them, the fermentation of excess harvests having long been an economic, as well as social, necessity.

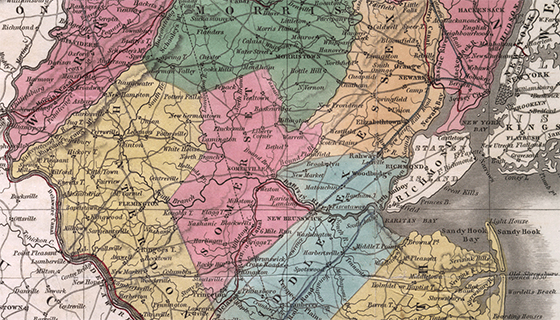

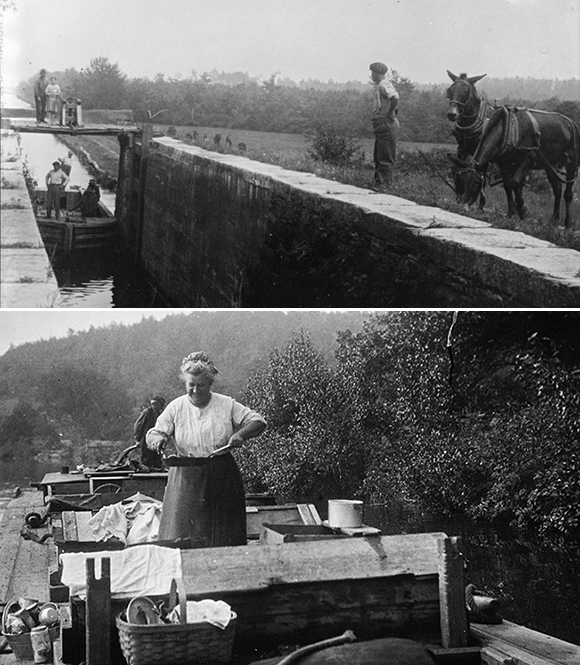

According to some sources, the need to get applejack from producer to consumer was critical to the development of the state’s infrastructure, spurring the construction of plank roads and gravel highways north and south, east and west. Early in the 19th century, supporters of the Morris Canal reversed this logic, arguing that the speed and efficiency of an engineered waterway meant that New Jersey growers could bring their apples to the markets of Philadelphia and New York without turning them into spirits. When the Morris Canal finally opened in the 1830s, the supposed result was “a large increase of profit to the farmer and of good morals to the community.”

That may be, but it’s hard to imagine not needing a few slugs of Jersey Lightning during that five day, 100+ mile journey from Phillipsburg on the Delaware to Jersey City on the Hudson, through the canal’s 23 locks and, especially, its 23 incline planes (which lifted each barge a whopping total of 1600 vertical feet). Regardless, given how quickly the railroad made the Morris Canal obsolete (completing the same journey in about five hours), its impact on the state’s morals was probably as short-lived as its profits. By the eve of prohibition there were more than 400 applejack distilleries operating in New Jersey.

Today, only one is left standing: Laird’s of Scobeyville, Colts Neck Township, Monmouth County. Members of the Laird family have been making applejack in New Jersey for twelve generations (even if their apples now come mainly from Virginia). Their outfit is the oldest licensed distillery in the United States and one of the oldest family owned and operated businesses in the country. Applejack’s bona fide New Jersey terroir is, therefore, unimpeachable. Having adequately explained the presence of “cyder spirits” in a cocktail named for New Jersey’s oldest, if not yet largest, city, we can now turn to less obvious dimensions of the Jersey City‘s cultural geography.

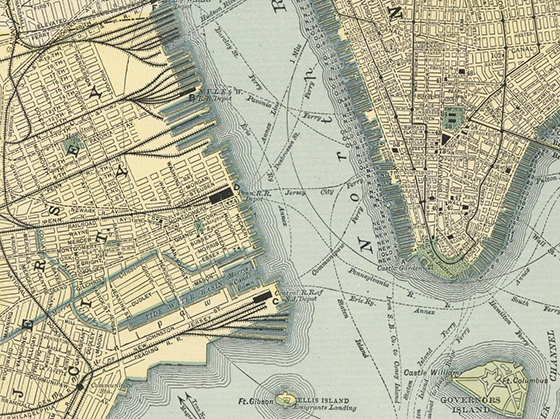

To put it another way: what’s up with the pineapple juice? As Imbibe recently observed (about a different drink with a similar provenance), “Jersey City isn’t exactly a tropical paradise.” But what kind of a place is it? More precisely, what kind of a place was it when The ABC of Cocktails appeared? The WPA Guide to New Jersey (1939) had this to say: “Millions of people carelessly regard Jersey City as a necessary rail and motor approach to Manhattan.”

[For drivers en route to the Holland Tunnel, necessary evil is probably a better description, whether in 1939 or today. Above is an Arthur Rothstein photograph shot for the FSA/OWI; below is an iPhone photo shot by a commuter sitting in what he called “ridiculous” traffic. The Seaboard cold storage building is evident in both.]

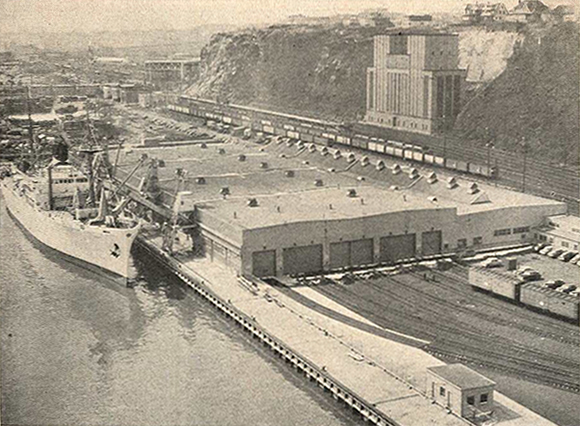

And yet, the Guide continued, “the propitious location of the city, close to the tremendous financial and consumer markets of New York City and metropolitan New Jersey, is an advantage equaled by its geographical position on upper New York Bay. This favorable situation has furnished Jersey City with shipping facilities which, in turn, have drawn motor routes and rail lines.”

This is not a minor point: Jersey City is On the Waterfront, even if Elia Kazan’s iconic film (1954) about longshoremen, unions, and corruption was shot on location one town over, in Hoboken.

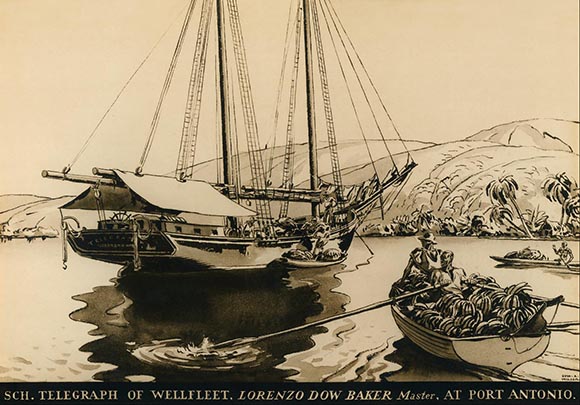

It is a little known fact that the enterprise that became the United Fruit Company began in Jersey City in 1870, when a sea captain named Lorenzo Dow Baker returned from Jamaica with 160 bunches of bananas and sold them on the streets of JC at a considerable profit. In 1899, Baker merged with his nearest competitors to become the United Fruit Company of New Jersey (state laws passed in the 1880s were famous for their generosity to big business; Standard Oil of New Jersey incorporated in 1885).

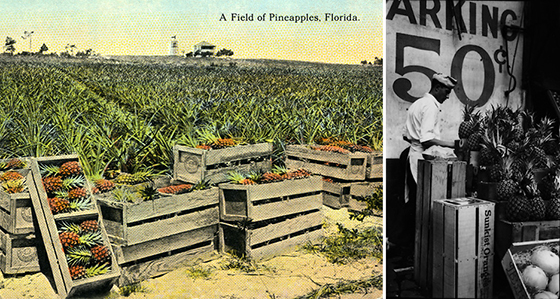

Around the same time, the United Fruit Company started growing pineapples in Florida, which was then the world’s largest pineapple exporter, and then shipping them north to the “tremendous” consumer markets of the NY/NJ metro area. Thus, however tenuously, we have established a connection between the pineapple and Jersey City, between the pineapple juice and the Jersey City.

Around the same time, the United Fruit Company started growing pineapples in Florida, which was then the world’s largest pineapple exporter, and then shipping them north to the “tremendous” consumer markets of the NY/NJ metro area. Thus, however tenuously, we have established a connection between the pineapple and Jersey City, between the pineapple juice and the Jersey City.

To conclude: by the middle of the 20th century, in between propping up Central American dictators and violating anti-trust laws, the United Fruit Company continued to dock its ships at Pier B (at the foot of Exchange Place) in Jersey City, while also operating the world’s largest mechanical banana handling facility in nearby Weehawken (at the foot of the Lincoln Tunnel ventilation towers). My research to date has not revealed where the pineapples were handled at mid-century, but today they are processed further inland on Jersey City’s West Side. The anonymous container warehouses hard by the Newark Meadows may lack the romance of the Hudson River, but the work still has its hazards: in 2013 a stevedore was nearly crushed when 1500 pounds of sliced pineapple came toppling out of the container he was unpacking.

Back on the waterfront, Jersey City has a post-industrial sheen that will be familiar to anyone who’s followed urban transformation since the 1970s. As for the Jersey City, even without the backstory, it’s a damn good cocktail.

Motor City/Brick City Comparative Ecologies, Part I: Geographies of Drinking 2 November 2014 No Comments

This is research towards a colloquy between Detroit, Michigan and Newark, New Jersey, two urban centers (the largest in their respective states) that are cataclysmically in flux, with compelling parallels and equally compelling divergences. This research does not explore the reasons for crisis and decline in Detroit and Newark, as these are well documented [see Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (1996) and Kevin Mumford, Newark: Race, Rights, and Riots in America (2007)].

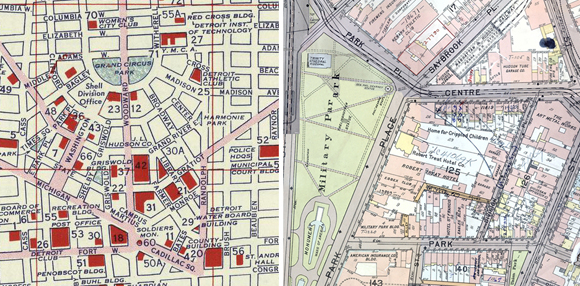

LEFT: Detroit, detail of Shell Oil Motoring Map, 1956; RIGHT:Newark, detail of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1926

Instead, this research probes fault lines of rebirth, retrenchment, resurgence, and renaissance that have defined each city in recent decades, especially since the uprisings of 1967. As an urban ecological exploration, this research considers profound differences in urban identity and urban scale, of physical and cultural infrastructure, and of physical and cultural interventions.

The Last Word Cocktail

3/4 oz. gin [pref. Two James Old Cockney, made in Detroit]

3/4 oz. green Chartreuse

3/4 oz. maraschino liqueur [pref. Luxardo]

3/4 oz. fresh lime juice, strained

Shake ingredients with ice and strain into a chilled glass. According to tradition, this venerable drink was invented in the Grill Room of the Detroit Athletic Club at some point during Prohibition. With the privatizing of public drinking in the wake of the Volstead Act, members-only clubs like the DAC became a focal point for socializing while imbibing. And Detroit’s proximity to Canada meant the city was awash in bootleg liquor. Though some claim it was the rotgut quality of bathtub gin that required masking by the herbs and cherries of the mixers, there is no evidence to support this. Chartreuse, made by French monks since the eighteenth century, has always had a rarefied air. Maraschino may well have been produced locally back then, northern Michigan being a major cherry growing region. The origin of the cocktail’s name is lost to history though the drink’s potency (Chartreuse is 110 proof) is an obvious source. In the past decade, the Last Word has rebounded in popularity due to the craft cocktail movement. This recipe is based on one published in Imbibe, borrowed from mixologist Murray Stenson of Seattle’s Zig Zag Café, who discovered it in Ted Saucier’s 1951 book Bottoms Up.

Detroit Athletic Club Founded in 1887, the Detroit Athletic Club moved to its present downtown location in 1915. There, a block east of the Grand Circus, Albert Kahn designed an imposing, freestanding, six-story palazzo seemingly more appropriate for the Gilded Age than the Motor Age, but absolutely in keeping with the parvenu ambitions of Detroit’s new industrial elite. The building featured state-of-the-art facilities for sporting and socializing, including a swimming pool, a gymnasium, meeting rooms, and banquet halls. The Club’s original restaurant, the Grill Room, had room for more than 200 members who dined in neo-Renaissance splendor.

At the back of the Grill Room was the Club’s first and, until 1936, only bar, notable for its dark woodwork, vaulted ceiling, and a large saloon nude called Lilly (painted by Julius Rolshoven in 1900). Sensuous and mildly exotic, with just a hint of the louche, Lilly presided over the mixing of the first Last Word at some auspicious, gin-soaked moment between 1920 and 1933. The Detroit Athletic Club was restored in the 1990s; today it has more than 4,000 members.

The Newark Cocktail

2 oz. Laird’s Bonded Straight Apple Brandy

1 oz. sweet vermouth

¼ oz. Fernet Branca

¼ oz. maraschino liqueur [pref. Luxardo]

Combine ingredients, stir with ice, strain and serve in chilled glass. This early twenty-first century cocktail is a Jersey-accented variation on the Brooklyn, a drink that dates to the classic cocktail era (circa 1900), but has long been overshadowed by the inner borough’s iconic Manhattan. The Newark has no connection with New Jersey’s largest city, having been developed by two New York City barmen and served at their East Village speakeasy. They looked west across the Hudson and, even further, across the Meadowlands when naming the new drink because Laird’s has been making applejack, a.k.a. Jersey Lightening, in the Garden State since 1780. During the colonial era, applejack had a place in New Jersey culture that parallels that of bourbon in Kentucky: it was distilled and consumed in great quantities and was sometimes used as a currency in trade. According to tradition, George Washington himself asked Robert Laird to share his recipe for “cyder spirits.” That Newark never had a cocktail to call its own is not surprising: historically, it has always been in New York City’s outsized cultural and economic shadow. Even during Newark’s heyday as a manufacturing center, it frequently stamped its products with a “made in New York” label because Gotham’s marketing power was so much greater than its own. This recipe for the Newark is based on one published in Imbibe, borrowed from one developed by Jim Meehan and John Deragon of PDT.

Newark Athletic Club once stood on a prominent downtown location overlooking Military Park, a few blocks north of the city’s main commercial crossroads at Broad and Market. As designed by Jordan Green in 1923, the Club was a façade-oriented riff on the commercial palazzo typology that was as formulaic and routine as Kahn’s Detroit Athletic Club was robust. Though established in a moment of Roaring Twenties optimism, the Newark Athletic Club was bankrupt by the mid-40s, a victim of the Great Depression, which also caused the suicide of several of the club’s founding, businessmen members.

With 300 guest rooms, the Club was easily adapted for use as a hotel, and this transformation seems to have prompted a lobby refurbishment by Morris Lapidus. Though more restrained than the over-the-top eclecticism that would characterize his later work in Miami Beach, Lapidus’ design for the club-cum-hotel provided a modicum of swank and glamour—enough to imagine the lobby bar as the setting for the creation of a cocktail named for the city. Alas, this would remain a wishful fantasy: not even the Newark novels of Philip Roth make fictional mention of such an event. By the time a Newark cocktail appeared in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, the Newark Athletic Club had been abandoned, demolished, and replaced with the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. Though NJPAC has two different bars, neither serves a Newark, and recent efforts to order one in the city were met with polite incomprehension.